How My Children (n=2) Acquired Absolute Pitch

source link: https://furiouslyrotatingshapes.substack.com/p/how-my-children-n2-acquired-absolute

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

How My Children (n=2) Acquired Absolute Pitch

and how you can probably help yours do it, too

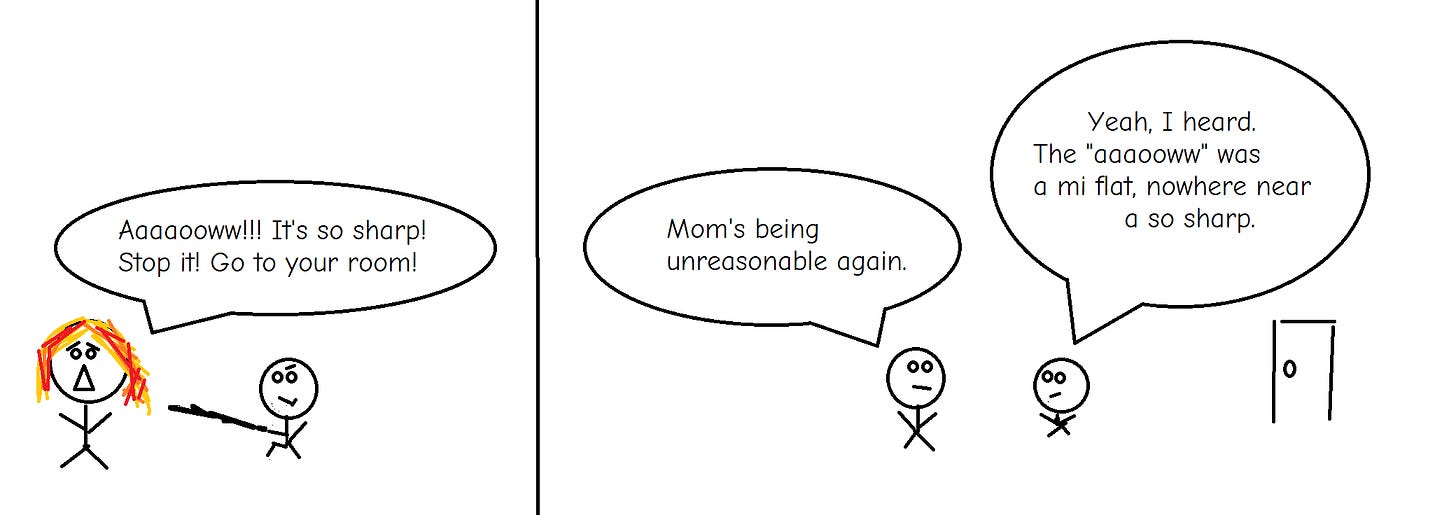

We were sitting outdoors in a café, wrapping up lunch on a warm summer afternoon, when my 5-year-old son started banging on the metal table in front of us. “Mommy, what’s this sound?” “It’s the sound of you banging on the table. And it’s quite annoying. Could you please stop?” My kids burst into laughter. “No, mommy, it’s F sharp!”

Both of my sons have absolute pitch (AP). This means that they can produce and identify musical pitches without any reference notes. If I ask them to sing a do, they instantaneously retrieve the exact pitch from memory and sing it. For my older son this ability has translated into what seems like a stunning effortlessness when it comes to his music lessons. He finds it easy to sit down at his instrument and improvise in any key. He composes beautiful music. He has been taking piano for a few years now, and even though he practices no more than 30 minutes a day on average, if he’s motivated, he can learn to play a simple Chopin composition within a week or two.

And he never struggles with memorizing the music he is assigned. It’s enough that he listens to a piece and practices it a few times: the music then plays in his head, and since he has the exact sound-to-note and sound-to-key mapping embedded in his brain, remembering what the piece sounds like translates into remembering how to recreate it. He often improvises his fingering on the spot, too, which tells me he doesn’t rely on his muscle memory a lot either.

Neither my husband nor I have absolute pitch. We have no professional musicians in our families and have no relatives with perfect pitch that we know of

. I’m personally very bad at music. I got some lessons when I was a child, but ear training exercises have always been very hard for me. In fact, I was forced to drop out from a music program that I attended in middle school because of how atrocious my aural skills were.

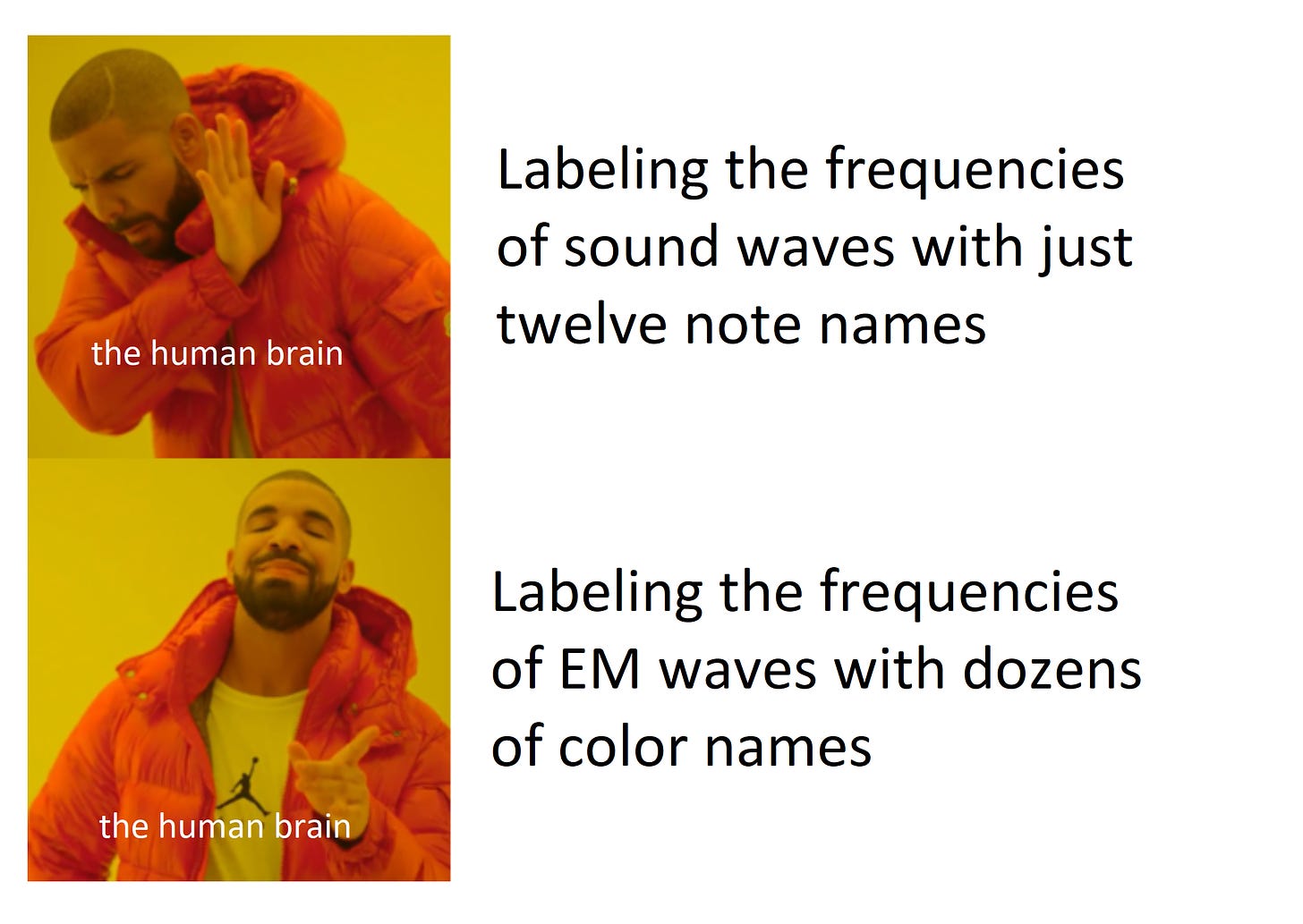

So when my first son was born, I decided to do my own research and figure out if I can somehow prevent my lack of musical genes from dooming him to musical mediocrity. That’s when I came across the work of Diana Deutsch and her writing on absolute pitch. Deutsch posed a question that really got me thinking: how come most people can identify and label colors with ease without needing any “reference colors” to do so, but absolute pitch is so rare?

Deutsch’s work is fascinating and I highly recommend it to anyone interested in the subject. I think it was her writing that sparked my interest in running my n=2 experiment to see if I can help my children develop a good ear, despite my initial skepticism. And skeptical I was. The culture I grew up in, especially my family culture, was that of a strong belief in genetic determinism, particularly when it came to musical talent. But Deutsch’s writing was intriguing enough for me to start questioning my long-held beliefs. For example, I appreciated her discussion of how children who grow up speaking a tonal language are more likely to develop/retain perfect pitch. You might think it probably has something to do with genes, but it doesn’t seem to be the case. The more fluent Asian students are in a tonal language, the more likely they are to have AP. And if they don’t speak a tonal language at all, they fare no better on AP tests than Caucasian students.

Let me highlight two other studies that influenced by thinking on this subject. One is the research done by Jenny Saffran, suggesting that all 8-month old babies have sensitivity to absolute pitch. The other is a Japanese investigation of 24 children, aged 2 to 6, who were intentionally trained to retain/acquire AP. (All but 2 who dropped out successfully acquired the ability through the training.)

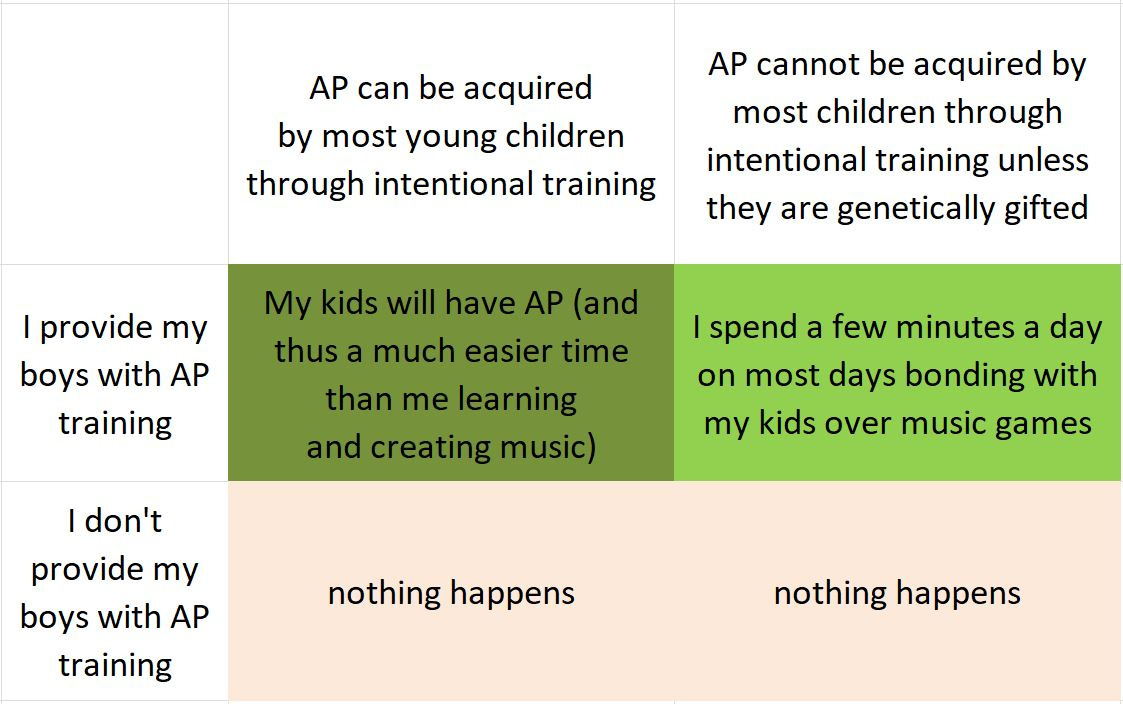

Now, to be clear, I was far from convinced that AP can be taught when I first started teaching music to my boys. Yes, sure, there were all those studies, but there are always studies to support your pet hypothesis… as well as the other guy’s pet hypothesis that just happens to run completely counter to yours. (Excuse my epistemic helplessness here — as a mother of young kids I didn’t have enough time to properly dissect the research.) Anyway, I was intrigued enough to give it a shot. Realistically, my expectation was that whatever early music exposure I would provide for my children might at least prevent them from inheriting my tone deafness.

So, how did I set about making this happen? The central idea was to consistently expose my boys to labeled pitches. There's no one-size-fits-all here — it's all about tailoring your approach to each child's temperament and interests. However, let me share the three key methods that proved effective for my family, in hopes they might be helpful to others: a labeled keyboard, solfeggio practice, and the use of a handful of apps.

Labeled Keyboard

When my older son was around 2, I bought him a cheap Yamaha keyboard, “cheap” being the key criterion. I wanted something for a toddler to be able to play with as he pleases, whether that meant an enthusiastic pounding on the keys or transforming the keyboard into an impromptu percussion instrument. Bottom line, you’ll need something sturdy and not so high-end that you’d feel bad gluing labels on it.

As for the labels, I used these stickers designed by Hellene Heiner. I like them because they're not only charming but also incorporate images alongside note names, making them ideal for kids who can't read yet. So, an image of a “door” represents do, a cup of “tea” stands for ti, and so on. (Heiner has also designed her own piano method, but we didn’t end up using it.) I always kept our keyboard in the kids’ room, ensuring they could explore it freely. And as they did so, they started associating the sounds with the corresponding note names.

Solfeggio

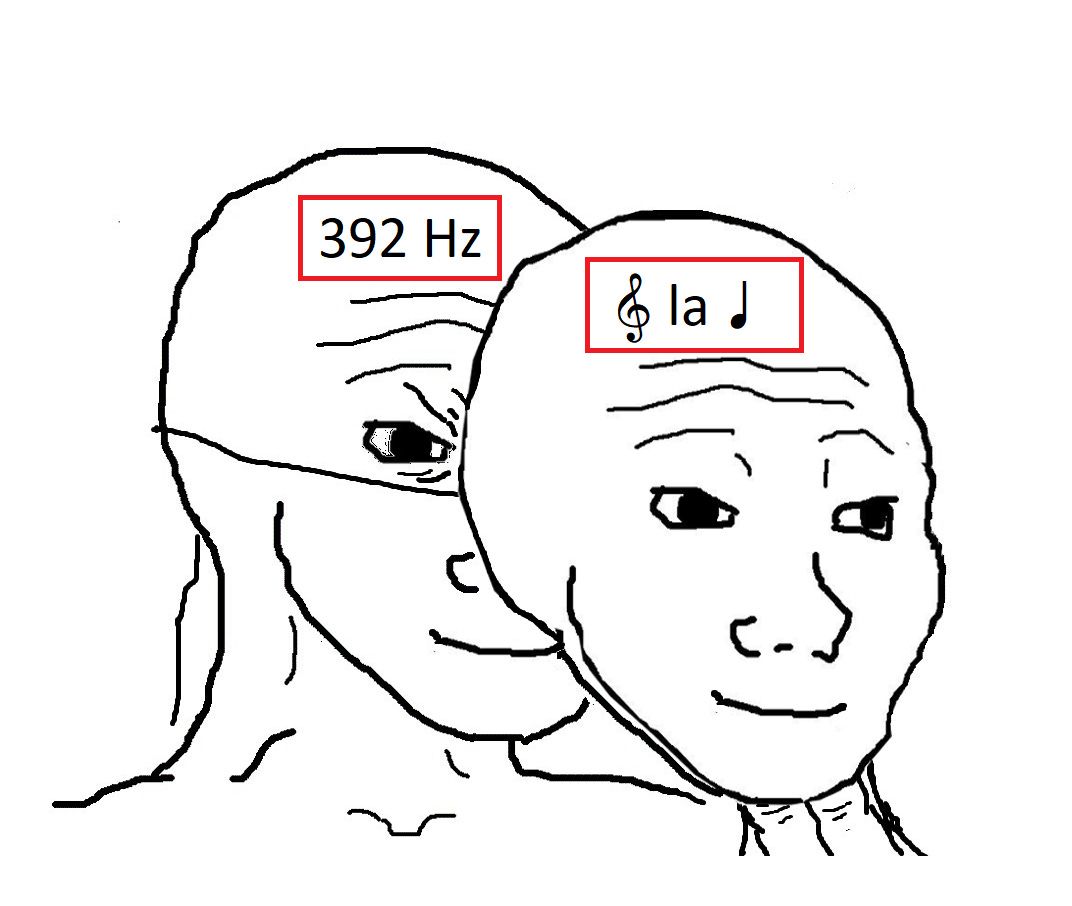

When teaching note names to my kids, I decided to go with solfeggio (do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti-do.) The reason was that I wanted labels that were distinct from letter names, which the children would encounter in many other contexts. The less ambiguity the better. Fortunately, teaching these names to little ones is really straightforward. You can start by simply singing the note names as you press random keys on your instrument, or sing nursery rhymes using note names instead of the lyrics. So, substitute mi-re-do-re-mi-mi-mi for “Mary had a little lamb”, and so on.

Now, I was only able to do the singing when I was in close proximity to the keyboard, as that was the sole reliable way for me to make sure my pitches were spot on. In the same vein, if you play any musical instruments around your kids, it’s crucial to always keep them properly tuned. I should also note here that it’s important to check whether any musical toys you might have at home (as well as any apps you might use) produce the correct pitches. Believe it or not, we once had a xylophone that didn’t!

At first, especially with younger children, you should focus on input. Don’t expect them to produce any significant output early on. Sure, you can encourage them to sing the note names with you, but don’t force it if they show no interest. Just keep singing to them yourself. You might also want to introduce some simple chords: do-mi-so, fa-la-do, ti-re-so, and so on.

Follow the children’s lead to see what types of activities entertain them the most. Always keep it light and fun.

On average, I likely spent about 5 minutes a day on these learning sessions on most days. At times, whenever my brain chose to hyperfocus on other endeavors, I skipped weeks or even months. It didn’t seem to matter in the end. I wish I had kept a better record of how much time I put in, but, frankly, once it became a habit to consistently name pitches and spend a few minutes a day playing with the labeled keyboard, it was so seamlessly integrated into our routine that I rarely gave it much thought.

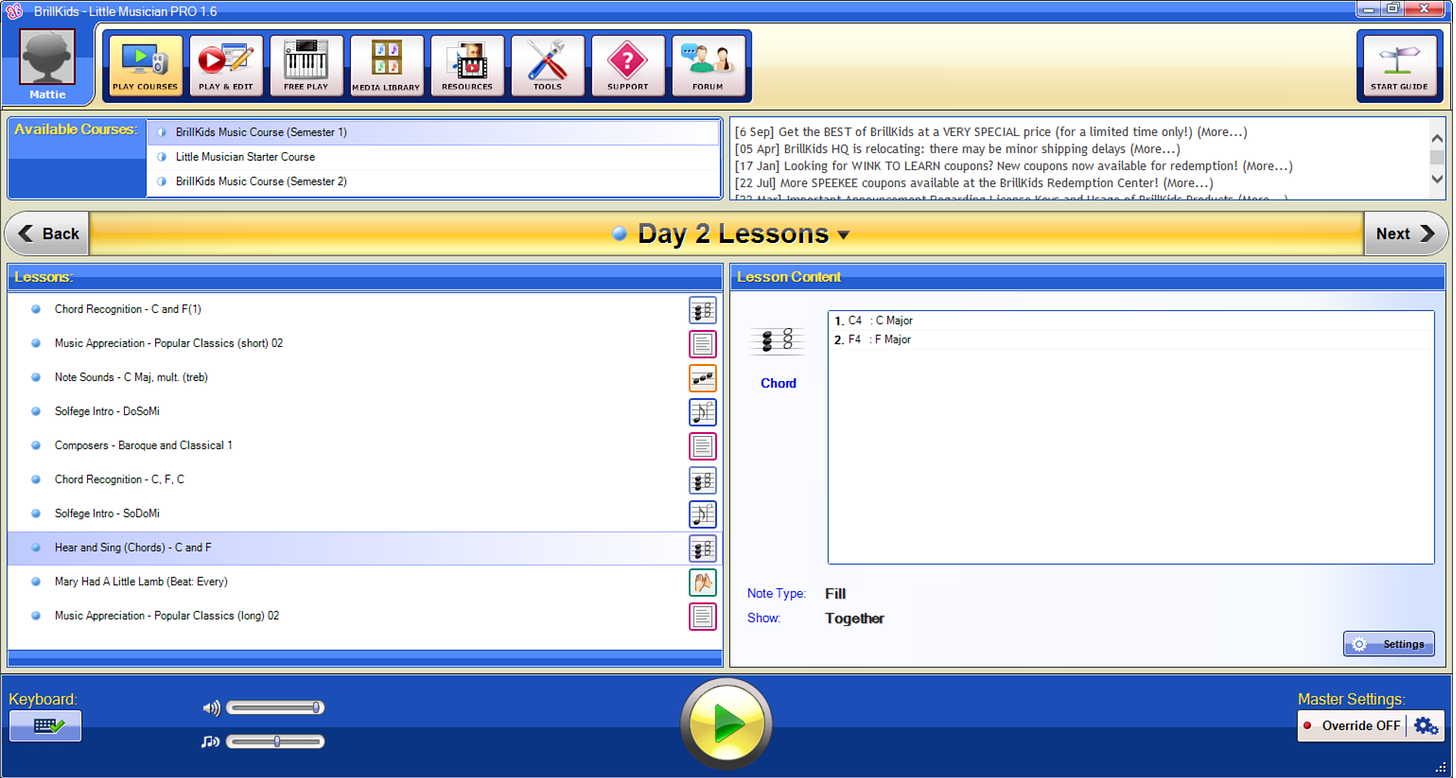

Apps: Little Musician

OK, so there’s this app. It seems to suffer from memory leaks. It doesn’t work on the Mac. It’s not cheap. It’s old and doesn’t work properly without Flash. It was written by people who are into this whole “right brain learning” thing, which I’m rather skeptical about. But if I were to point to what I believe was the number two most important tool in our absolute pitch acquisition journey, second only to the labeled keyboard play, this would be it. So, bottom line, despite its flaws, I do highly recommend it.

Without further ado, here’s the link. You should be able to download a free version that includes a few sample lessons to give you a sense of what it’s all about. If you feel it’s too expensive, at the very least, you can take a look at the kind of activities it offers and then recreate them at home

.

There are a few reasons why I appreciate Little Musician. First, it made it easy for me to be consistent. To be perfectly honest, during the baby and toddler years, my reserves of energy and creativity often ran low. With this app, all I needed to do was launch the lesson, sit with my child for 5 minutes while listening, oohing-aahing, clapping and what not, and then I was done. No creativity and not much energy required. I used this program with both of my kids when they were around 2.5-4. Not very consistently, but I did use it a lot. It has the chords, it has the sounds, it has the note names. And the children liked it.

Other Apps

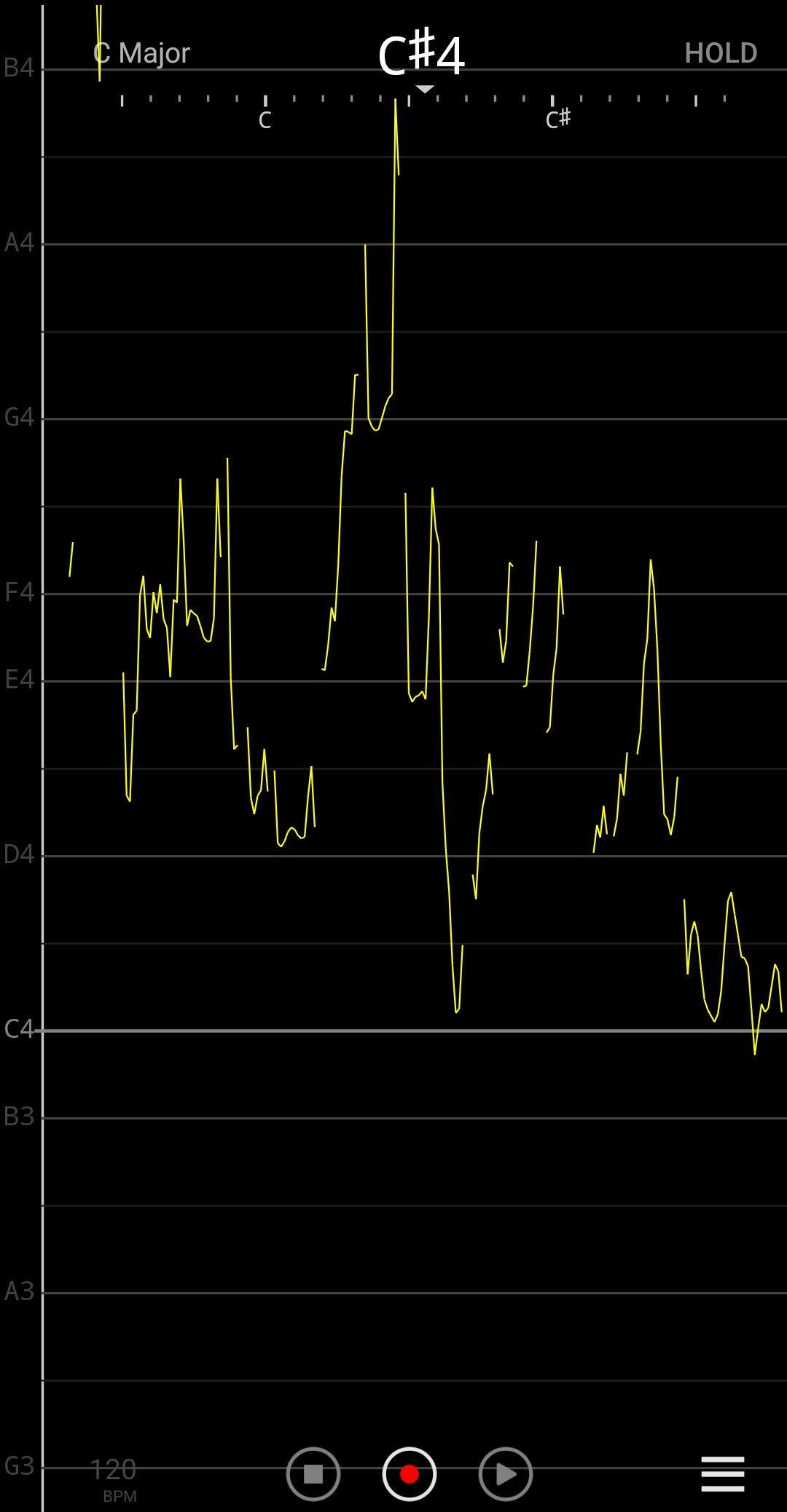

I also highly recommend getting an app that recognizes pitches. This way, whenever there is some persistent sound in your environment, you can figure out what it is and draw your child’s attention to it. “Oh, listen, honey, the truck is beeping. The beep is a so.” And later on in your journey, you can use it to verify if your kids are producing the correct pitches. “Can you sing do for me? Spot on!”

The app I currently use on my Android phone for this purpose is called VocalPitchMonitor, but, to be perfectly honest, I didn’t do my due diligence on it, so I have no idea if it steals my soul and sends it to Eastern Europe. There are plenty of similar apps, so you can choose something that works for you.

There are also some cute apps on the iPad that are designed to teach notes to children. None in particular stand out, and we didn’t use any of them regularly, but they are an option.

(As an aside, I did use Piano Maestro and Simply Piano, two really good apps, when my children were older. However, that was for the boys’ early piano instruction rather than ear training.)

Mandarin

While I don't believe this to be particularly relevant in our case, I thought it would be worth mentioning for the sake of completeness: I am attempting to teach my children Mandarin. Even though fluency in a tonal language is associated with a higher likelihood of acquiring AP, I don’t believe it played a role in our situation. I’m not a Chinese speaker and am learning the language as I teach it to the children. My boys do get some exposure to native speakers, but it’s limited to a few hours a week.

And so we kept going, singing songs in solfeggio, playing on our labeled keyboard, identifying various sounds in our environment and using our apps until one day I discovered that my older son, then aged 6.5, had actually developed perfect pitch. To say that I was astounded would be an understatement. After all, I had very little confidence that any of the methods we used would successfully cultivate AP. But it happened. Euterpe graced us with her inspiration.

I still remember the day I tested my older son for the first time. I was humming a tune, and he began correcting me. Now, as I may have already mentioned once or twice, I’m really bad at music. My immediate thought was that I was messing up the melody, but it turned out the melody was fine. My son didn’t like the way I sang it, however, because it was in the wrong key. I was incredulous. I even momsplained to him that humans, with rare exceptions, can’t identify actual pitches without reference sounds. Yet as I was saying this, it started dawning on me that I was perhaps now dealing with one of those rare humans.

So I proceeded to play random notes on the keyboard for him to name, and he identified all of them with ease. He could recognize all the white key sounds across several octaves. Amazed, I kept repeating the test: early in the morning, before he could hear any possible reference sounds, and during walks, when I would ask him to produce various pitches for my phone app to recognize. And he consistently got them all. Well, almost all.

Black keys still stumped him at that time. But he knew that he didn’t know them. Over the next few months, he learned to identify them as we started to play and label them more frequently. I think it’s OK to focus just on the white keys first. I am guessing that once sensitivity to absolute pitch is established, naming the black key sounds is just a matter of attaching labels to them. It’s like when you know green and blue, and then see this weird in-between color: all you have to do is learn that its name is “teal” and you’re all set.

After discovering the older boy’s perfect pitch 3 years ago, I renewed my efforts with my younger son, who was about 3.5 at that point. We restarted the Little Musician lessons and I made a greater effort to include some keyboard play on most days. I also began conducting little quizzes: after turning out the lights, I’d play some notes and ask the boys to name them. My little boy wasn’t all that good at it at first, but that was perfectly fine. I think it helped to set the expectation that this was something learnable. One of the earliest signs of his sensitivity to absolute pitch was his ability to consistently produce the middle do without any reference sounds at all. The next milestone was recognizing all the white keys of the middle octave, followed by the white keys of the adjacent octaves. He can sing them without any reference sounds, too. He’s 6.5 now, and not terribly eager to practice, so we don’t do it often. I’m curious to see if he’ll develop the ability to name the black keys in the same way his older brother did. (I’ll try to be back here with an update.)

Parents often have the desire to give their children that which they themselves were missing when growing up.

That’s what motivated me to introduce my boys to music when they were very young. I know there’s some disagreement as to whether absolute pitch is a big deal or not, and there are, of course, plenty of unbelievable musicians who don’t have it. But the fact is, by giving my boys AP, I made sure that, unlike me, they will find learning music easy. AP is not a necessary condition for that, but it is sufficient.

So what’s next for my children’s musical education? At this point, I have outsourced most of it. I sit with them during their piano practice, but while I’m still able to help my younger boy, the older one just wants me there for company. Some time ago, they started working with a great, creative and very chill piano teacher. My older boy is also taking a few online music classes in his two non-dominant languages. (My kids are trilingual and I always look for ways to increase their non-dominant language exposure.)

The ability to play, sing or compose has always seemed to me like one of the most intellectually enriching and satisfying arts. Whether you’re enjoying making music in solitude, expressing your emotions with Chopin’s nocturnes, or using music to bring people together at a party by playing just the right tune, it’s a gift. And I now believe that parents — even those who can’t carry a tune to save their lives — can present their children with this gift of musical aptitude. All it takes is a bit of daily exposure when the kids are very young. If you do decide to try this at home, I hope you come back and share your results in the comments.

Yes, this actually happened.

Although my mom (who knows nothing about music but is firmly committed to the idea that absolute pitch is determined not by early training or exposure but solely by genetics) suggests that my great uncle may have had AP. My great uncle, whom I remember very fondly, was a peddler specializing in trading and repairing accordions and guitars. He had no formal training but could certainly play his instruments by ear. My husband’s younger brother, who started his music lessons at a younger age than my husband, is also very good at music, and his teachers have always praised his talent.

The Eguchi method followed by the Japanese absolute pitch training program relies on chords. Chords might be important for some reason, although I’m not entirely sure if they are. It’s probably safer to just throw them in.

I have no relationship with the authors of the app in question, other than having purchased their products in the past. And the provided link is not an affiliate link, in case you're wondering.

On the other hand, parents also often wish to provide their children with whatever it is that they themselves had and cherished. Rick Beato is one famous example of a musician training his child’s ear to an exceptional degree.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK