Fixing product design career paths with the Mirror Model

source link: https://uxdesign.cc/fixing-product-design-career-paths-with-the-mirror-model-76152b7e547

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Fixing product design career paths with the Mirror Model

Product Design career paths are broken. Fundamentally and inextricably. Not out of malice, but out of no constant and clear drum beat; nobody noisily shouting with vigor that “our career paths are broken!” It’s time somebody said it, so why not us?

If you’re here, you’re most likely a designer, a manager, or an enthusiast. And you’re probably wondering how these career paths are actually broken: In what way, and from whose point of view? Furthermore, wouldn’t it be safe to assume that by now, even if they were broken, some company somewhere would have resolved the issue by developing a clear, consistent, and fair model that rewarded both Creators and Managers?

Seemingly, no.

Product Designers’ job pathways disproportionately emphasize an upward trajectory that leads to management. This leads to an industry that stifles the careers of highly-creative people who don’t want to manage, putting their personal and professional growth on hold because no appropriate role exists for them to grow into. These people get maxed out at the Principal Product Designer level (even at Meta) and feel handcuffed to their current role or feel forced to jump ship to earn more money and recognition.

This begs the question: what would a fair leveling model for Product Designers look like, in which both Creative Types and Manager Types are appreciated, rewarded, and compensated equally? In my early career, I didn’t consciously recognize this was a problem. But now that I understand it, I’ve struggled to locate a model that provided resolution. I’ve looked at Google, Meta, Microsoft, and many startups. I’ve dug through Medium and came up somewhat empty-handed (links to follow). I’ve even talked to multiple HR staff who all seemed to pull from the same leveling handbook.

In short: I couldn’t find a model, so I made one.

Defining the Problems

Before we jump to solutions, let’s reflect upon the problems in their most basic form:

- Career paths for Product Designers exist because, like any worker, they want opportunities to take on new responsibilities, increase impact, tackle new challenges, and earn more money.

- Product Design career growth is often broken up into two paths: Individual Contributor and Manager. The Individual Contributor path (or IC path for short) is built for those who draw the rectangles. The Management path is for the managers, who draw fewer and fewer rectangles as they grow their careers. For most of this thought piece, I refer to the IC path as “the Creative Path.”

- The Individual Contributor/Creative path famously caps at the Principal level, meaning anyone who loves to design and is good at it has no choice for career growth but to become a manager. Usually, this is undesirable. Imagine being told that the only way to make more money is to stop doing what you love. It’s disheartening.

- A common justification for this final cap for Creative careers is that somebody has to manage them, which means the managers are always more senior. Some also argue, by this logic, that because managers are always more senior, then the only way to get ahead is to become a manager. I understand and agree with this, up to a point. Yes, somebody has to be in charge of the “workers” so as to assign them work and hold them accountable for that work. But, I don’t believe management has to be the only path available for growth (as articulated in my model).

How do we fix this? How do we help the Individual Contributors grow their careers without subjugating them to the wallows of management work? We can resolve this, but let’s first understand the current state of things.

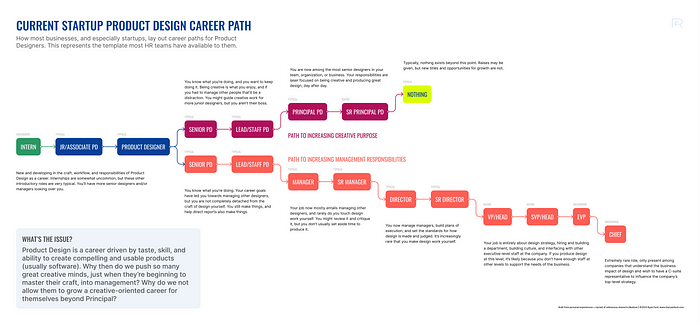

The Broken State of Startup Career Paths

Looking at the chart above, you’ll see a starter career path (represented in green and blue) that branches off into two new paths: Creative/Individual Contributor work and Management work. These paths are represented by the related roles and titles along the way, starting at an Internship level and growing up to a Chief Design Officer level.

The chart looks this way because: Startups usually don’t think as deeply as they should about Creative/IC development, which is why you’ll notice that the Creative Path (in maroon) effectively dies after the Senior Principal Product Designer role. Meanwhile, the Management Path (in salmon) is more thoroughly defined and for one simple reason: the people typically responsible for building these career paths are not designers, they’re HR and Managers.

The HR playbook is decades old and has barely had to evolve alongside technology. It remains rooted in business dogma, where there were always “the workers” and “the bosses”—a clear split between the two. The workers did the work, the bosses did the bossing, and there was a simple linear path up the corporate ladder: as you grew, you became a manager. The birth and explosion of the tech industry changed this a little, but not quite enough to support the needs of Product Design, and not within the average startup. After all, Product Design is a relatively new career and has barely had time to mature.

The Broken State of Enterprise Career Paths

If startups don’t necessarily have their acts together, what about Enterprise businesses? Behemoths like Google, Amazon, Meta, and Microsoft—they must certainly have identified and resolved this problem, right?

Seemingly, not so much.

Enterprise companies have tried to avoid the problem by eliminating most titles and replacing them with alphanumeric designations. They did this to resolve title designation confusion across departments, allowing a band (like IC6) to have a common set of expectations and compensation whether you’re an Engineer, Product Manager, or Designer. You’re no longer a Lead Product Designer, you’re an IC6. It’s easier, in theory.

However, once you do the math to determine where the Creative/IC path dies off, just like with startups it tends to be right around the Senior Principal Product Designer level. For Meta/Facebook (graphic above), there doesn’t appear to be an IC9.

Curiously, there is an IC9 for Engineers at Meta. This leads us to a meaningful new way of thinking:

Engineering Career Paths as a Template for Product Design

Much like Product Designers, engineers are frequently given two career paths that divide Code-Writing Engineers (CWEs) from Managers. But unlike Product Designers, engineers at some companies have built further development for CWEs in recognition of the fact that some of them are just so good, so brilliant at writing code that putting them into a management track would be bad for the business.

Imagine applying the same thinking to Product Design.

The Proposed Solution: The Mirror Model

Enter The Mirror Model (above), which seeks to resolve our core problems. It’s called as such because both Creative and Management paths act as mirrors of one another.

To build this, I used Engineering Career Paths as a template for Product Design, and in doing so more opportunities began to expose themselves. Some notes on the thought process:

- Career growth is broken up into Zones to help designate responsibilities, expectations, and more. These zones also help indicate the path of authority: Zone 3 Management is responsible for Zone 2 Creative, and so forth.

- Alphanumeric designations have been juxtaposed with titles to bring clarity to both startups and enterprises alike.

- These alphanumerics have evolved from their initial FAANG state to make more sense (in my view). They now clarify track type first, role-and-level second. For example: what Meta calls D1 (which is a Director-Level 1) is now designated as M-D1 (indicating Manager-Director-Level 1). While this may seem redundant, it helps mirror the way the IC roles are now treated, such as IC-D1 (Individual Contributor-Distinguished-Level 1).

- After the Senior Principal Product Design level comes the Distinguished Product Designer, followed by Product Design Fellow. These are titles ripped straight from Engineering. If Distinguished and Fellow titles exist for engineering departments, the alphanumeric designations remain transferrable and equivalent, cross-functionally.

- The core purpose of the Management track remains in place: more emphasis on people, strategy, and accountability as you move up that ladder.

- The underlying purpose of the Creative path is transformed: more emphasis on craft, innovative thinking, tools, and empowering teammates through design. This is work commonly expected of those in the Management path, but in practice, it’s unreasonable given many managers are not necessarily great designers (just like many designers are not necessarily great managers).

- The Creative Path mirrors the Management Path in both quantities of roles, seniority of roles, and potential paths to Chief Design Officer (if available). The reason both paths culminate in the same C-suite role is that, at such a senior level, the CDO should be more-than-knowledgeable about design with regard to craft, strategy, and everything else wrapped up in it.

- As a reflection of how things work in real life, there’s a degree of transferability between the Creative and Managerial paths in Zone 2. This is important because, at this stage, a designer might try management on and realize it’s not for them. Or, a designer might try to remain an IC but know they long for more mentorship opportunities. This transfer already happens in real life so we’d might as well plan for it.

What do Distinguished and Fellow levels do?

To answer this question, we need to first level-set on what the Principal Product Designer does relative to what the Product Design Manager does. Principals have shown a strong capacity to create, while Managers have shown a strong capacity to manage. The Principal’s daily concerns are ideas, projects, and tangible output, while a Manager’s are plans, strategies, and (most importantly) people.

As a Manager moves up their career ladder, they are increasingly responsible for greater quantities of people—moving from small teams, to large teams, to departments, to whole organizations. When that Manager finally becomes a VP, they are responsible for an entire design department, or perhaps multiple design departments.

What also happens during management growth is a decreasing ability to remain focused on design quality, upskilling fellow team members, introducing or even building new tools, and more. Ironically, managers are typically held responsible for these very activities—things that will help improve the abilities of the team, yes, but also fall outside of people and strategy. In other words, as a manager becomes more senior, their ability to directly impact creative quality decreases, but expectations of creative quality control increase. That doesn’t seem effective.

Enter the Distinguished Product Designer and Product Design Fellow, two roles which are now the yin to the management track’s yang. While the Director concerns themself with managing managers and articulating the way work gets done, the Distinguished concerns themself with facilitating quality and guiding creative growth for the organization. Some tools in the Distinguished and Fellow Product Designer’s kit might be:

- Reviewing work in progress and critique

- Teaching the design team, regularly, how to improve their craftsmanship

- Teaching brand new methods of work & thought

- Upskilling designers on using new tools

- Building new tools

- Acting as a senior conceptual thinker / investing time and energy into north star project discovery

To put it yet another way, in its simplest terms: Distinguished and Fellow levels are all about impacting how good the design work is, while Director and VP levels are about impacting how good the people and organization are. They complement one another, and they’re connected, but they’re also different methods of thought.

Objectively, one could argue that these tasks are already performed by managers. That’s true. In some organizations, these tasks are even given to DesignOps (a thought piece has even been written around this subject). I’m arguing that maybe they shouldn’t be. Maybe managers should focus on people problems and structural organizational problems, DesignOps should focus on systems (its whole purpose, after all), and creative people should focus on creativity. The more experienced one is with something, the more qualified they are to own that work.

Keep in mind, the Mirror Model is a proposal—a mental model still in its infancy. If implemented, modify it to suit your business needs, articulate your unique role expectations, and make it your own. Personally, I’ll be using it to influence the way my own teams get built in alignment with Engineering and Product Management. I hope that you too will find it inspirational and that it can serve as a foundation for career evolution. Thanks for reading.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK