It’s not (just) the economy, stupid

source link: https://kevinhateswriting.medium.com/its-not-just-the-economy-stupid-ad35292b6881

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

It’s not (just) the economy, stupid

Recent events should be the nail in the coffin for the centrist popularism discourse

In recent years, pundits from the more conservative wing of the Democratic coalition have adopted a philosophy that they call popularism. The motivation behind popularism “is that the people who run and staff the Democratic Party are much more educated and ideologically liberal” than typical Americans, and so if these allegedly far-left elites are left to their own devices, they will craft policies and campaign strategies that are out of step with ordinary voters. To correct for this supposed bias, popularists urge campaigns to utilize opinion polls to find out “what the median voter actually thinks” and then tailor policymaking and communications to those findings.

The appeal of popularism lies in its apparent common-sense logic: To win elections, Democrats should do and say things that are popular, and they should avoid doing and saying things that are unpopular. But in practice, popularism tends to be biased toward the conservative political leanings of its proponents. There are substantive criticisms of popularism that attack its basic premise, questioning whether voters really do care as much about policies as popularists claim. But even if we accept its fundamental reason for existence, there are real flaws in how popularist pundits analyze and interpret data, and often a more rigorous and careful analysis will lead in the exact opposite direction from the one popularists head in.

A major focus of popularist punditry is on the working class, defined by pollsters as people who haven’t graduated from a four-year college. Popularists observe that working-class voters have gradually become more and more Republican over the past two decades, and they posit that if Democrats could appeal more to this group, they would stand a much better chance at winning elections. Ultimately, this means that Democrats should scale back their messaging on social issues and focus on “kitchen table” issues related to the economy.

This argument is not without evidence. A July 2022 New York Times/Siena College poll showed working-class voters favoring Donald Trump over Joe Biden by about 20 percentage points, and college-educated voters favoring Biden over Trump by about the same margin. Working-class respondents were more likely than college-educated voters to say that an economic issue is the most important issue facing the country, and college-educated people were more likely than working-class voters to say that a social issue is the country’s most important issue. The popularist claim seems to be well supported: The different voting preferences of working-class and college-educated voters appear to be due to the differences in how they feel about economic and social issues.

This story gels with the persistent, baffling, narrative about Republicans “building a multiracial coalition of working-class voters.” While it is true that over time Republicans have won a larger and larger share of working-class votes, and that greater percentages of non-white voters have cast ballots for Republicans in recent years, to call the Republican-voting electorate a relatively “multiracial coalition” compared to Democratic voters is an absurd exaggeration. Instead, the increasing share of working-class voters who vote Republican has come largely from one demographic: white people. In the 2020 presidential election, 85% of people who voted for Donald Trump were white. The number of white Trump voters outnumbered non-white Trump voters nearly six to one, while for Biden that ratio was less than two to one. Working-class white Trump voters outnumbered all non-white Trump voters by four to one. More Black people voted for Biden in 2020 than all the non-white people who voted for Trump combined.

The overwhelming whiteness of the Republican electorate is a clear indication that not all working-class demographics are the same. While two thirds of white working class voters cast ballots for Trump in 2020, huge majorities of women, Black voters, Latinx voters, and voters younger than 30 went for Biden. Together, these groups make up more than half of working-class voters.

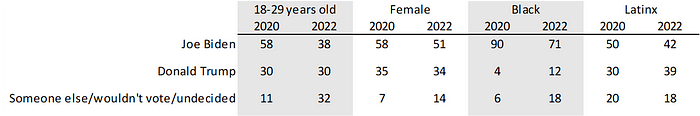

The July Times/Siena College poll shows support for Biden waning among these four groups. But by and large, this decrease in support for Biden and the Democrats is not translating into increased support for Trump and the Republicans. Unlike white working class voters’ migration rightward, these solidly Democratic-leaning, majority working-class groups are signaling that they will check out of the process rather than switch parties. To find out why, we should ask what makes these groups different from the group of white working-class voters.

According to the US Census, a little over half of people who don’t have college degrees are white. In the 2020 presidential election, two thirds of these white working-class voters cast ballots for Trump. This means that as many as one third of working class voters are conservative, white, Trump-supporting Republicans.

Is there any Democratic campaign strategy that can reach these voters? It is doubtful. The vast majority of Republican voters continue to think the 2020 election was stolen, for example. If these voters haven’t been convinced that Joe Biden’s 2020 victory was legitimate — after dozens of losses in court, an impeachment, hours of January 6 Committee hearings, and a total lack of even the tiniest shred of evidence that the election was stolen — then there’s no reason to believe that any amount of truth-telling or persuasion can reach them on any issue. Indeed, even on the economy, an issue that is supposed to be grounded in material reality, polling data shows that conservative voters are guided far more by ideology and partisan identity than by substance. Republican voters’ opinion of the strength of the economy is mostly determined by the party affiliation of the president: If the president is a Republican, Republicans voters say the economy is good, if a Democrat, they say it’s bad. During the last year of Barack Obama’s second term in office, just 18% of Republican voters said the economy was good. As soon as Trump took office, that number skyrocketed, reaching a peak of 83% in 2019. When Biden took office in 2021, the figure plummeted back down to about the level it had been during Obama’s final year in office. In contrast, the percentage of Democratic voters rating the economy as good hovered around 40% consistently from the Obama to the Trump years, only dropping in 2020 as the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic struck.

The takeaway is that a huge chunk of working-class class voters — the Trump-voting white working class voters that make up about one third of the total working class demographic — are simply unreachable for Democrats, even on kitchen table issues. These voters say they care about the economy and that the economy is bad, but kitchen table messaging and policymaking will fail to persuade them because their outlook is mostly determined by partisan identity. For most white working-class voters, attitudes about the economy are not what drive voting preferences. Instead, it’s the reverse: Partisan identity drives both attitudes about the economy and voting preferences. Over the past five years, this partisan identity has calcified as Trump has fused the GOP brand with the cult of his personality. This is a serious social and political problem, but it will only be solved through truth, accountability, justice, and reconciliation — not by lowering the price of gas or ground beef.

Rather than pick away at the impermeable wall that surrounds Trump-voting conservative white working-class voters, Democrats should focus their gaze on groups of working class voters who could conceivably vote for them. Voters who are Black, Latinx, young, or female all went for Biden in 2020, and collectively these overlapping groups make up more than half of all working-class voters.

Here, the Times/Siena College poll reveals a surprising result totally glossed over by every popularist write-up: Young, female, Black, and Latinx voters are more ideologically similar to college-educated voters than to white working-class ones. The July 2022 Times/Siena College poll shows people from these groups caring far more than white working-class voters about social issues — indeed, women, young people, and Black people were all more likely than even white college-educated voters to say that a social issue was the nation’s most important problem. Likewise on the economy: Female, young, and Black respondents were no more likely than college-educated white voters to name an economic issue as that country’s number one problem.

What this all means is that the broad category “working class” is inadequate for describing voters’ attitudes and preferences. Instead, Democratic strategists should approach the working class as two distinct groups: those who could conceivably be persuaded to vote for Democrats, and those who could not. The latter group, made up largely of white voters, has shifted from the Democrats to the Republicans because most of them are partisan conservative Republicans who resent progressive politics. The former group — which includes women, young people, and non-white people — comprises constituencies that mostly voted for Barack Obama, Hilary Clinton, and Joe Biden. The July 2022 Times/Siena College poll shows these voters drifting away from the Democratic Party and threatening to join the reserve army of nonvoters. To craft effective messaging and policies that will win elections, Democrats should focus their efforts on these working class groups, forgoing white working-class voters.

At first blush, this strategy might seem like it is giving up on white working-class voters. But large percentages of female and young voters, and a smaller percentage of Latinx voters, are white. By focusing on the features of their identity that make them likely to be Democratic-leaning voters, a strategy that bypasses the white working class actually ends up targeting those members of the white working class who are most persuadable. Paradoxically, the best way for Democrats to secure white working-class votes is for them to ignore the white working class in their messaging.

The unique history of racial capitalism and patriarchy means that the American working class is fractured politically. When analysts treat the working class as a single, homogeneous monolith, it looks like working-class voters are socially conservative. In reality, this is an illusion resulting from the downward suction applied by the white majority. When we look at groups not defined by whiteness, we instead see that plausibly Democratic voters are as socially progressive as college-educated voters. According to the logic of popularism, then, Democrats should do exactly the opposite of what popularists most often say. To win working-class votes, Democrats should run campaigns that embrace progressive stances on social issues.

This is what the data tells us. But will it work? Recent events, including a blowout referendum victory for abortion rights in Kansas and a recent uptick in Biden’s approval rating, indicate that it will.

The recent surprise landslide defeat of a Kansas anti-abortion referendum helps illustrate how social issues can score victories for Democrats.

The margins by which the so-called Value Them both Amendment was defeated left little doubt about how Kansans feel about abortion rights. In a state where Republican voters outnumber Democrats by 70%, the No campaign won by nearly 20 percentage points and outperformed Biden’s 2020 presidential election performance in every single county in the state. In Leavenworth County, which Trump won by 21 points in 2020 with nearly 60% of the total vote, No on Value Them Both defeated Yes by 18 points.

If the margin of victory was shocking, the turnout was truly incredible. The August 2 election in Kansas became the most-attended primary election in state history, and turnout was actually higher than almost ever midterm general election in Kansas history (2018 was the only exception).

Democrats, who need to motivate Democratic-leaning working-class voters, should see the result of the Value Them Both referendum as a clear sign that abortion is a key issue to embrace this election season.

An early August increase in President Biden’s approval rating, coming on the heels of a trio of good news stories for Democrats (including the Kansas referendum), further supports the idea that social issues — including abortion, climate justice, and protecting representative government — are assets for Democrats.

The August 9 Reuters/Ipsos poll tracking Biden’s approval rating rose to 40% for the first time since the Supreme Court handed down its June 24 decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization eliminating the constitutional right to abortion. In line with the popularist assumption that the economy drives voter attitudes, much of the commentary about this rise in Biden’s popularity has focused on improved economic indicators, including falling gas prices and potentially stabilizing inflation numbers, as the key factors in the Biden glow-up.

This explanation is implausible for a couple of reasons. By early August, gas prices had been falling steadily for a month and a half, but all throughout that period, Biden’s approval rating had continued to decline. And the groups with whom Biden’s popularity rose — women, non-white, and college-educated voters especially — were all reported in the July 2022 Times/Siena College poll to care less about the economy and more about social issues than other groups. (The data from the Reuters/Ipsos poll makes it difficult to tease out the specific approval ratings from Black, Latinx, and young voters, as those groups are not separated out for analysis.)

Instead, the rise in Biden’s approval rating is best attributed to a storm of good news that came in late July and early August. One of these stories was the blowout victory for abortion rights in Kansas on August 2. Another was the surprise announcement of a Senate deal on climate change legislation, curiously dubbed the Inflation Reduction Act, which, though its name wouldn’t tell you this, will be the largest investment in combating climate change in United States history. Finally, more than half of the time period over which the poll was conducted came after the breaking news about the FBI search of Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago Club home in Palm Beach, Florida, a sensational event that was quickly interpreted as a sign that the Justice Department was getting serious about prosecuting the former president, possibly for crimes related to the January 6, 2021 insurrection.

Biden’s approval rating has since fallen a bit since its August 9 peak even as gas prices have continued to fall. There is no correlation between economic conditions and Biden’s approval rating. Instead, the news cycle turned over, and as it did, the impact of the positive news stories about the Kansas referendum, the Inflation Reduction Act, and the FBI search of Trump’s home waned.

Contrary to what popularist pundits say, plausible Democratic voters in the working class care a great deal about social issues, oftentimes even more than college-educated voters do. Recent tracking shows that there is no correlation between falling gas prices or plateauing inflation and a rise in Biden’s approval rating. Instead, the uptick in Biden’s approval in early August coincided with a news cycle that featured positive stories for Democrats on abortion rights, climate change, and investigations into Donald Trump’s criminal dealings.

There are no referenda on abortion between now and the November 9 midterms. It is unlikely that congressional Democrats will pass any more signature legislation with the appeal and impact of the Inflation Reduction Act. And whatever progress is made on the investigations into Trump and his criminal conspirators will live behind the airtight, leakproof seal of the Justice Department.

If Democratic leaders want a wave of progressive voters to usher in victory for them in November, then they will have to be proactive about stirring up enthusiasm. This means pivoting away from talking about gas prices and inflation and towards social issues like abortion rights, climate justice, gun control, and defending representative government.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK