How we will fight climate change

source link: https://noahpinion.substack.com/p/how-we-will-fight-climate-change

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

How we will fight climate change

And how we will not fight climate change

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results” — unknown

It is now abundantly clear that Americans are not going to support a big government push to rapidly decarbonize the U.S. economy. The popular urgency simply is not there.

This is very bad, because urgency is very warranted. The devastating effects of climate change are not something waiting for us in the far future — they are here today, as the Europeans experiencing a brutal, unprecedented heat wave can unhappily attest. The fact that Americans still basically don’t care that much about climate change shows that the required urgency will not manifest until it’s too late.

Over the past few years, I’ve seen U.S. climate activists and leftists — who are becoming less distinguishable in terms of rhetoric — make a mighty attempt to generate a sense of urgency among the American public (and the global public). I have seen Greta Thunberg thundering at the UN: “How dare you?! You have stolen my dreams and my childhood!”

I have seen climate activists tell everyone to read books like David Wallace-Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earth. I have seen Sunshine Movement activists angrily confront Senator Dianne Feinstein in her office. I have seen Netflix release a disaster movie about how everyone is complacent about the climate. I have seen climate strikes and Extinction Rebellions. I have seen any number of articles about climate anxiety.

None of it has worked. The Green New Deal is so dead that uttering the name now sounds like a bitter joke. Other ambitious plans like Jay Inslee’s were ignored. Biden’s more realistic plan was killed by Joe Manchin. Polls like the one that Wallace-Wells cite above consistently find that climate change is a relatively low priority for Americans, even among Democrats.

It is now time to conclude that the “scare people into making a big push” strategy that climate activists and leftists have been using over the last few years has decisively, utterly failed. People ought to be scared. They ought to support a big push. But this is simply a thing that is not going to happen in the time frame we need it to happen.

So what can we do? Give up and sit around all day feeling a gnawing certainty in the pits of our stomachs that the planet is as good as cooked and there’s no reason to go on? You can go ahead and do that if you want, but I’ll pass, thanks.

I want to talk about the strategy that I think will be effective against climate change. But first, this requires talking about the strategy that has been ineffective, and why it has failed.

The failed strategy: Degrowth, anticapitalism, and doomerism

Why have climate activists and leftists failed to generate a sufficient sense of urgency in the American public? One reason is that many have embraced the idea of degrowth. This is the idea that economic growth is environmentally unsustainable and should be halted (at least in rich countries). I wrote about degrowth pretty extensively here:

One fundamental fact here is that degrowth is politically unacceptable to lots of people. Halting growth in rich countries and continuing it in poor countries would not make much of a difference to climate change (despite the poorly informed claims of degrowth salesman Jason Hickel). Global degrowth with continued catch-up growth in poor countries would require a vast diminution of living standards in rich countries — we’re talking about the reduction of transportation, energy use, etc. by the U.S. middle class to the level of a country like Thailand.

It’s possible that Americans would accept a vast diminution of their living standards as an alternative to death. But this is a very heavy ask — it enormously raises the bar for how much popular urgency climate activists will have to create in order to motivate the country to action. Thus, embracing degrowth makes the politics of climate change much, much more daunting.

There’s also the fact that degrowth is ridiculous on the merits. It would require central planning of the global economy that goes far, far beyond anything ever attempted. And even if this impossible task were successfully carried out, a halting of economic growth would make it much more difficult to afford the research and deployment of new green technologies necessary to sustain even a constant level of living standards. It also doesn’t help that the research literature behind degrowth is incredibly shoddy:

So embracing degrowth isn’t just politically unpalatable — it also makes climate activists look out of touch with reality. It is why reasonable progressive intellectuals have rejected the idea. Yet some activists stubbornly continue to push the idea. Greta Thunberg rails against “fairytales of eternal economic growth”. And here is Genevieve Guenther, founder of the organization End Climate Silence:

If you think that some supportive comments on an NYT article on degrowth mean the idea has legs, at a time when Americans are up in arms about $4.50 gasoline, you really need to think again.

(Side note: This NYT interview is really, really bad. When the interviewer confronts “pioneering economist” Herman Daly with the question of why growth can’t continue to shift to things like software and services that use fewer natural resources, Daly ludicrously responds that economic growth should be defined as growth in resource use — which is not how GDP is actually calculated anywhere in the world — and that dematerialized GDP growth should be called “development” instead of “growth”. Thus, the entire article relies on one economist’s flagrant ignorance about how GDP is measured.)

Some legacy environmental groups don’t necessarily use degrowth rhetoric, but practice an ethos of degrowth — blocking solar plants and wind farms and other types of economic growth that are crucial for decarbonization. Wally Nowinski wrote a guest post about it here:

Now, it’s important to note that many U.S. climate activists do not embrace degrowth. The Sunrise Movement, for example, advocates for a Green New Deal that would entail substantial economic growth:

There’s just one catch: The organizations that advocate Green New Deal style programs support growth, but only if it comes via the abolition of capitalism.

Anticapitalism has become one of the major themes of climate activism for a while now — longer than degrowth, actually. There are endless articles written about it, in the New York Times, in the Guardian, in the Nation, in online publications and city newspapers. There are popular books about it. Anticapitalism is the animating force of the Sunrise Movement and of the Green New Deal. Several of my favorite climate writers, despite their enthusiasm for green technology, routinely bash capitalism on Twitter — it has become a meme and a motif of the movement.

Now, it’s true that free markets, on their own, will not solve climate change fast enough, because free markets don’t take externalities like climate change into account (in fact, this is the subject of most environmental economics research, which NYT interviewee Herman Daly utterly ignores). In order to decarbonize fast enough to save ourselves from some very bad outcomes, we’re going to need government to step in — to subsidize green energy so its costs decline, to tax old coal and gas plants so they get retired faster, to build new grid infrastructure, to facilitate the infrastructure for electric vehicles, and so on. Government needs to do a lot.

But this doesn’t mean that the capitalist foundations of our economy need to be overthrown — in fact, doing so would be counterproductive. Countries that set themselves up explicitly as anticapitalist tend to have very bad environmental records. One reason is that a well-functioning economy requires a hefty amount of both markets and government — when you try to abolish capitalism, your economy tanks and you don’t have the money to switch to green technologies, to develop new green technologies, to clean up pollution, etc. And when the economy tanks, people get mad, and governments often appease them by falling back on short-sighted, environmentally destructive consumption subsidies.

So abolishing capitalism would be very bad for the climate, because despite all the Green New Dealers’ claims, it would effectively end up as a form of degrowth. It is just as heavy an ask, and thus massively raises the threshold of urgency that’s required to motivate the American people to take action.

Climate activists who make these heavy, heavy asks of the American people — degrowth and-or the abolition of capitalism — are forced to try to pump up popular urgency to extremely high levels, in order to clear the very high hurdle they have set up. This is one reason so many climate activists turn to doomerism — apocalyptic rhetoric about how it’s too late to save the world.

In the past year or two there has been a pushback against doomerism in progressive circles. Ezra Klein wrote a New York Times op-ed called “Your Kids Are Not Doomed”, in which he argued against leftists’ increasingly common declarations that it’s not worth bringing children into a world ravaged by climate change. There have been many other op-eds arguing against doomerism. David Wallace-Wells himself wrote an excellent op-ed last year called “After Alarmism”, noting that while the best-case climate scenarios have deteriorated, the worst-case scenarios are looking more unlikely. Thanks to renewables and better data, the “business as usual” scenarios now look more like 2.5-3C of warming — still devastating, but not as apocalyptic as the doomer scenarios that have been thrown around in the last decade.

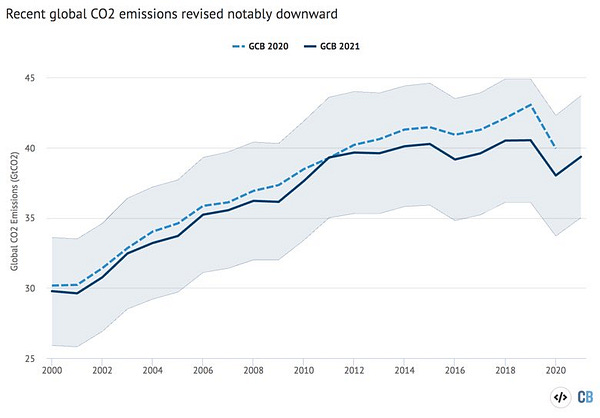

Yet in activist circles, there still seems to be a taboo over expressing the kind of can-do optimism that’s usually necessary for sustained social movements. When I noted that data revisions show that global carbon emissions have been constant for a decade, many cheered the news, but some activists got angry at me for perceived complacency:

Trumpeting modest, initial successes is not complacency. It’s a way of countering doomerism — of saying “Yes, we can do this.” Attacking anyone who shows heartening data is really just a way of encouraging doomerism. (For staunchly anticapitalist activists, there is probably another motivation — a fear that heartening data will be used as evidence that climate change can be fixed without overthrowing capitalism.)

Degrowth, anticapitalism, and doomerism are not a single unified package — many climate activists subscribe to only one or two of the trio of bad ideas. And some climate activists don’t subscribe to any of the three. But enough subscribe to at least one of the three that together, this trio of ideas has heavily compromised the effectiveness of activism in generating the degree of popular urgency required for bold policy change. We have strayed from the positive, can-do rhetoric of late 2000s activists like Van Jones. Degrowth and anticapitalism have raised the bar for popular urgency too high, while doomerism has simply turned activists to passive surrender and depression rather than spurring non-activists to desperate action.

A new approach is needed. And fortunately, we have a new approach ready at hand.

The strategy that will work: A technology-focused, bottom-up, whole-of-society effort

In settling on a strategy that works, we (i.e. anyone who actually wants to stop climate change) must grapple with the failure of the big-push strategy that just met its ignominious end at the hands of Joe Manchin. There is no way of spinning this as a good thing; the planet isn’t doomed, but it would have been far easier to decarbonize the U.S. with a big government push. And we should not stop rhetorically wishing for one. But unless we get very lucky in the election this November, that big push is not coming soon, we need to go with plan B in the immediate future.

Leah Stokes, a political scientist at UC Santa Barbara, argues persuasively that there’s still a lot we can do:

Democratic leaders are not waiting for Congress to act. Gov. Gavin Newsom of California signed a budget bill this month with a historic $54 billion in climate investments. New York State is moving ahead with its ambitious plans to cut carbon this decade. And in Washington State, Gov. Jay Inslee is leading an all-out mobilization to decarbonize: from landmark building codes to bold climate goals.

Individuals don’t have to wait, either. Although the climate bill would have helped millions of Americans afford cleaner technologies sooner, many Americans can already make the switch.

Most electric vehicles are now cheaper to own than gas cars, starting on Day 1…Inflation hasn’t hit E.V. drivers nearly as hard as it has hit people with gas-powered cars. No wonder sales for E.V.s are through the roof and many automakers are planning to go all electric…For those who prefer two wheels, affordable electric bikes are now widely available.

We can also work to eliminate fossil fuels from our homes, by installing induction stoves and switching from gas or oil-fired furnaces and hot water tanks to heat pumps…

In the long run, we are going to win.

State-level policies and individual choices will not solve the problem at the global level, of course. But to be frank, neither will U.S. policy, even if we had passed Build Back Better — after all, the U.S. only produces 13.5% of global emissions, even after accounting for offshoring/imports. The biggest way that a U.S. decarbonization push would have helped the world is by pushing down the cost of renewables (because the more you build, the more prices go down) and making it in other countries’ economic self-interest to install those renewables.

Even without that big push, state-level policies and individual adoption of renewable technologies can push down prices via learning curves. Learning curves are a positive externality that works against the negative externality of climate change.

In addition to electing state leaders like Inslee and Newsom, and buying green tech ourselves, we can do a lot to raise awareness within the worlds of technology, business, and the civil service. In a post a year ago, I wrote:

The most important single factor in the fight against climate change is technology…[N]ow that these technologies are becoming cheaper than fossil fuels…fighting climate change is becoming economically easy, or even advantageous…

And this did not happen on its own; technological progress does not simply fall from the sky. It required researchers to dedicate their lives and careers to inventing better energy technologies, instead of working on better semiconductor design or protein folding or whatever. It required government bureaucrats and legislators to fund energy research instead of starving it of money. It required entrepreneurs like Elon Musk to invest their lives and their fortunes in battery companies that pushed down the cost of batteries through mass production and scale effects, rather than starting companies that made death drones or ad tech. It required managers at large companies to risk investing their companies’ capital budgets in green energy tech. And so on, and so forth.

There is a virtuous cycle of awareness, effort, and adoption — a bottom-up, whole-of-society effort. The best description of this that I’ve read is Robinson Meyer’s description of a “green vortex”:

Last year was a singular, awful moment in economic history, but even accounting for the effects of the COVID-19 recession, America’s real-world emissions last decade outperformed the [2009] Obama bill’s targets. From 2012 to 2020, real-world U.S. emissions were more than 1 billion tons below what the bill would have required, according to my analysis of data from Rhodium Group, an energy-research firm…

What gives? America is supposed to be doing nothing right. Yet we’re making progress anyway. How? Why?…

Decarbonization…proceeds by a self-accelerating process that I have called “the green vortex.” The green vortex describes how policy, technology, business, and politics can all work together, lowering the cost of zero-carbon energy, building pro-climate coalitions, and speeding up humanity’s ability to decarbonize. It has also already gotten results. The green vortex is what drove down the cost of wind and solar, what overturned Exxon’s board, and what the Biden administration is banking on in its infrastructure plan…

The idea that drives the green vortex is: Practice makes improvement. The more that we do something, whether baking a cake or manufacturing electric vehicles, the better we get at it…The green vortex leverages this idea to describe a positive feedback loop…As technologies develop, they get cheaper. As they get cheaper, more companies adopt them. As more companies adopt them, their leaders grow more comfortable with climate policy generally—and more supportive of pro-technology policy in particular. As more corporate leaders support climate policy, coalitions change, governments can pass more aggressive measures, and the cycle expands and begins again.

In other words, everyone pushes wherever they can push. We campaign for climate-aware state leaders. We build technologies that make decarbonization easier, if that’s what we’re good at doing. We persuade our bosses and the companies we own to adopt renewable technologies. We use our investment choices to direct capital toward companies that produce or use renewables. If we work for the civil service, we try to design and implement regulations in ways that favor renewables.

And most of all, we persuade the nation. We talk about how beating climate change is about abundant cheap energy. You won’t have to give up your car or your truck; you’ll just have an electric one instead, and then you won’t have to pay for gas. You won’t have to ration electricity or wear a sweater in the winter; renewables will make electricity cheaper, not just greener, so that you can consume more of it. We persuade Americans not just to support pro-renewables policies, but to try renewable technologies for themselves.

This requires a very different kind of rhetoric than degrowth, anticapitalism, or doomerism. It is not the language of sacrifice — it’s the language of abundance. It’s not some fantasy of socialist utopia — it’s cheap good stuff you can buy right now. It’s not a dire, angry, hectoring leftism that demands sacrifice under threat of destruction — it’s a positive, can-do individualist progressivism that’s in keeping with the way America has improved itself in the past. Beating climate change is part of the Abundance Agenda.

This is our Plan B, but as Robinson Meyer writes, it’s not such a bad fallback. In fact, it sounds like a pretty fun social movement to be a part of. A heck of a lot better than sitting around waiting to die in a fire, anyway.

Update: Some good news! Manchin has apparently agreed to pass some kind of a spending bill.

This is not the long-hoped for big push against climate change — indeed, fossil fuels are slated to get a hefty share of government investment. That was probably inevitable, given the Russian energy shock. But the good news here is that some of the money will go toward renewables and energy storage, and that money will help push down the price of those things even more. So this will aid the “green vortex”, by making renewables and storage even cheaper, which gives the private sector — and even more crucially, other countries — more incentive to replace fossil fuels in the medium term.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK

David Wallace-Wells @dwallacewells

David Wallace-Wells @dwallacewells

Noahpinion

Noahpinion Dr. Genevieve Guenther @DoctorVive

Dr. Genevieve Guenther @DoctorVive

Sunrise Movement 🌅 @sunrisemvmt

Sunrise Movement 🌅 @sunrisemvmt

Noah Smith 🐇🇺🇦 @Noahpinion

Noah Smith 🐇🇺🇦 @Noahpinion

Dr. Leah Stokes @leahstokes

Dr. Leah Stokes @leahstokes