When Joss Whedon Was Our Master

source link: https://www.vice.com/en/article/v7d34y/when-joss-whedon-was-our-master

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

When Joss Whedon Was Our Master

It's Hard to Be a Woman in the MCU

While Tatiana Maslaney lights up every frame she appears in, I can’t help but be apprehensive about She-Hulk: Attorney At Law. There just aren’t a lot of ways to be a woman in the Marvel Cinematic Universe.

There’s a lot to like about the She-Hulk trailer. It’s got a breeziness about it, and it leans into the zaniness of its premise (which is literally just, “girl-hulk is an attorney, hilarity ensues”). But it’s a little hard to get excited for a story about a woman in the MCU. The franchise doesn’t have an awesome track record for writing women, and I am wary of setting myself up to be disappointed again.

Take Wanda Maximoff, also known as the Scarlet Witch, played by Elizabeth Olsen. Though Olsen imparts a lot of humor to the character, and once she turns villainous (again), chews the scenery with zeal, there’s just not a lot to the character once she’s been run through the gamut of both Marvel movies and her own Disney+ TV show. When you meet Wanda, she’s a refugee with misplaced anger, lashing out at the de facto heroes until they convince her to switch sides. After she joins the Avengers, she is put through so much trauma it’s like the character’s ability to hold complex concepts shrinks. Wanda just becomes an avatar of pain, one that is mostly centered around her ability to have and raise a family.

If it was just the one character, that would be one thing. But Black Widow, played by Scarlett Johansen, also has a major aspect of her character revolve around her inability to have children. In Age of Ultron, she tells her fellow Avenger the Hulk that she feels like a monster because she was forced to undergo a hysterectomy as part of her spy training in Russia. It doesn’t feel any better to see the scene in context. What’s just as worrying about both Scarlet Witch and Black Widow is that at the end of their character arcs they die, though Olsen says that she hasn’t discounted the possibility of appearing in future MCU films.

Parent-child relationships define a lot of other MCU women. Thor’s sister Hela is motivated by her father having imprisoned her in hell. Nebula and Gamora are defined by the torment they suffered at the hands of their evil adopted father Thanos. The Wasp acts largely as an instrument of her father’s will. Above all else, they’re men’s daughters.

When not defined by their roles as daughters or as people who can’t bear daughters, MCU women are often not women at all, but children. In Doctor Strange and the Multiverse of Madness, the titular doctor is joined by America Chavez, a plucky teenage girl. In Hawkeye, the titular Hawkeye is joined by Kate Bishop, a plucky teenage girl. Black Panther has a sister, Shuri, who is written exactly like a plucky teenage girl despite not being a teenager. Prior to the Captain Marvel film, most of the female characters in MCU movies were love interests, leaving Captain Marvel herself as one of the few female characters who doesn’t have a plot line or character arc revolving around wanting to be a mother or otherwise settle down. (There are at this point several Captain Marvels, one of whom is another’s daughter; their associate Ms. Marvel is a plucky teenage girl.) Even the ones who do have more going on in their lives than being a parent or child tend not to get a lot of focus. Jessica Jones, the titular hero of the Netflix TV show Jessica Jones, was a three-dimensional person, but although the character was well received, Marvel’s partnership with Netflix ended and there’s no telling if we’ll ever see that character again.

Not all women in the MCU are written in the same way, and characters like Valkyrie have potential, but it is telling when you struggle to think of women in the Marvel Cinematic Universe who aren’t primarily focused on having children or being someone’s child or aren’t basically children themselves. She-Hulk, as a lawyer who has starred in some very good and deliberately goofy comics, from which the show seems to be taking its cues, will hopefully represent a change, but as much as I am excited to see her literally lift up her date and carry him to the bedroom, it also makes me wary. Sure, professional women in their thirties do date and want to have children, but I hope that She-Hulk has enough room in it for this character to be defined by other things.

ORIGINAL REPORTING ON EVERYTHING THAT MATTERS IN YOUR INBOX.

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from Vice Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.

‘Doctor Who’ Finally Has a Black Doctor, But It's Still ‘Doctor Who’

After half a century of being on the air, the BBC science fiction romp Doctor Who has finally cast a non-white actor in its lead role. Unfortunately, this means I might watch some Doctor Who in the future.

If you’ve never seen Doctor Who, do not feel obligated to watch it. Ostensibly it’s a science fiction adventure series about a time traveling hero and his (or, as of very recently, sometime her) companions. Think of it as like Star Trek, but instead of an American military force visiting a Roman Empire-themed planet, it’s a couple of British people on holiday going to the actual ancient Rome with a time-traveling alien called the Doctor. My dad got hooked on the series in the 1970s, when it was being broadcast on PBS, and when the series rebooted in 2003, he passed that appreciation down onto me.

Over time, liking Doctor Who has felt more like a curse than a blessing. At its best, it does fulfill the basic promise of science fiction episodic television—once a week, you get transported to a fantastical place where our heroes will solve a problem in a clever way. It’s just that the show has frequently been uneven in its modern era, not sure whether to follow in the footsteps of episodic television of the past or to treat Who as a prestige enterprise.

For my part, I feel like Who has always been better when it takes things an episode at a time. Although the initial series revival, with the excellent Christopher Eccleston as the Doctor, played a little bit with long-term plotting, each season since then has focused less on the monster of the week and more on an overarching mystery. But delving into the series’ mythology to create mysteries or conspiracies has diminishing returns. There is simply not a lot to say about the Daleks as an allegory for fascist regimes that has not already been said in the 50 years of the show being on air. That, and the actual mythology of the show to dive into is simply goofy-ass.

The Doctor is a Gallifreyan Time Lord, now the last of his kind, who gallavants across the universe fighting Daleks and Cybermen and meeting Shakespeare. (Interestingly, Gallifreyans can choose what kind of shape they regenerate into after they die, and apparently, the Doctor did not see any reason to anything other than a white man until quite recently.) Prior to the show’s reboot, these enemy aliens were often props made of cardboard or plastic tubing painted silver; treating them as serious antagonists is kind of a struggle when you see their humble beginnings. Doctor Who has the hallmarks of an edutainment children’s show, but the prestige format presents it as serious adult fiction. The result feels campy, but often the show and its plot lines are too dour to take advantage of that tone. I had to take a break from the show after the season where the characters face genocidal lizard men in the center of the earth because somehow they managed to make that premise incredibly boring to watch.

Despite knowing that I am no longer a Doctor Who fan, seeing that a black actor has finally been cast in the role has given me the urge to revisit the show. Each Doctor has their own, mostly distinct personality. The most famous Doctor, Tom Baker’s, was the kind of eccentric, scatterbrained fop that has been most associated with the character, but Eccleston’s Doctor was a kind of rough around the edges guy in a leather jacket, who remarked slyly to someone who noted his northern English accent that “lots of planets have a north.” Matt Smith played the Doctor as a very old man suddenly in a young man's body, his limbs rubbery and always in motion, as if he was somehow surprised that he could move that fast. Peter Capaldi, for his part, leaned into his already extant image as an angry guy, but tried to convey a sense of majesty and brokenness of an alien who is so old now that they’ve kind of just given up on pleasantries. Ncuti Gatwa, best known for his work on Sex Education, will be the next actor to put their specific spin on this character that theoretically can be anyone from anywhere. We simply don’t know what a black Doctor looks like or feels like, and having watched this show with my dad, I’ve always hoped I’d be able to find that out.

There have been many acclaimed actors from the UK to take up the mantle of the Doctor—besides Eccleston, Paul McGann and David Tennant have also played the role, and Jodie Whittaker played The Doctor for the time being. Ncuti Gatwa will soon join that roster. I’m glad that he gets a chance to play one of the best-known, and longest-running, science fiction protagonists of all time. I also hope that he will soon be on a better show.

Why Are People So Mad About These Star Wars Vespas in The Book of Boba Fett

The latest episode of The Book of Boba Fett has some Star Wars fans asking a question: What even makes something a Star Wars, anyway? Getting to the root of that question is more complicated than it first appears.

When you think of Star Wars, you might think of lightsabers, Jedi, or the twin suns of Tatooine. The iconography of the series is highly identifiable, and also very marketable, having been an internationally successful science fiction series since its debut in 1977. It was once the brainchild of George Lucas, an experimental filmmaker with a fondness for pulp adventure series. As time went on, and Star Wars got more and more successful, he grew disinterested in being the series’ shepherd, and sold it to Disney over a decade ago.

Unlike Lucas, who rarely added to the franchise himself, instead letting its expanded universe develop into a not entirely consistent web of additional texts, Disney, has taken a more centralized and in some ways maximalist approach, with a new series of movies as well as multiple television shows and an entire section of one of the Disney theme parks devoted to the series. One would assume that more Star Wars would make Star Wars fans happy, but even before the fandom fallout from The Last Jedi, that has not been true at all.

The Book of Boba Fett as a show should be an easy win for the fans, given that Boba Fett has long been a beloved character despite—or, as pages-deprived fantasy author George R.R. Martin would have it, perhaps because of—not actually doing much of anything in the movies. The Disney+ show gives you a lot more Boba Fett, including his backstory, which fans have speculated about for decades. But the most recent episode inspired some nerd ire in response to Jon Favreau and Robert Rodriguez’s presentation of the Star Wars universe.

In the episode, the titular bounty hunter gets an assist from a gang of cool teens riding futuristic Vespas. The episode itself isn’t too interesting—most of it feels like wheel spinning while the overarching plot of the season kicks into gear—but Vespas are a real sticking point for some fans, who feel that they don’t fit into the rest of the dusty, brown landscape of the Tatooine criminal underground.

It’s easy enough to poke holes in that idea—George Lucas, first off, very evidently loves hot rods, which are all over his early feature film American Graffiti. You don’t have to look very far to find aspects of that culture in other Lucas Star Wars films too, from the way that Han Solo talks about his Millennium Falcon, to “now this is podracing,” to the more overt references to 1950s rock n roll culture from Attack of the Clones.

Deciding what is or isn’t a Star Wars, though, isn’t up to the fans. In the case of The Book of Boba Fett, it’s ultimately up to Rodriguez and whoever he answers to at Disney. That doesn’t mean fans are obligated to like it—this episode was truly not very good—but to say that it isn’t fundamentally Star Wars is both not true and not the responsibility of the fandom to decide.

What Star Wars is is always changing, and will continue to change if you’re going to make more of it. Disney infamously (and confusingly) first deemed the widely-beloved expanded universe that had flourished under Lucas to largely not be canon before allowing many of its elements back in, so that even if you’re persnickety about these things it’s truly unclear what even counts as canon Change isn’t necessarily good or bad. Sometimes it will be lame. Sometimes, pushing the conventions of Star Wars into new places can lead to exciting takes on the series, as demonstrated by the critically acclaimed series of anime shorts Disney produced called Star Wars: Visions.

With the television shows, Disney treats the universe of Star Wars as something closer to a Dungeons and Dragons setting, with established locations and characters for each series to play around with, rather than a continuous narrative franchise. For the most part, especially when it comes to The Mandalorian and Dave Filoni’s work on the Clone Wars cartoons, this has worked out a lot better than trying to continue the story from the movies. The story of Luke Skywalker and his relatives and the rebellion against the Empire has now played out three times on the big screen. Exploring other kinds of stories in this vast universe might unearth another hero worthy of such reverence.

All of this aside, there are hundreds upon hundreds of populated worlds in the universe of Star Wars, containing unexplored cities which contain unexplored neighborhoods Some of them are home to fan favorites, like droids and jizz music and alluring Twi’leks. Some are inhabited by disgraced Jedi, who roam the land like the ronin from Lucas’s beloved Akira Kurosawa films. Others still might have hot rods on or in them. If your imagination is so limited that that seems like an impossibility, then maybe Star Wars isn’t the problem.

How Much Princess Diana-Themed Entertainment is Too Much?

Spencer. The Crown. Diana the Musical. Diana: Queen of Style. All TV and film properties that suggest the same thing: One of the most influential cultural figures of late 2020 and 2021 was a woman who died in 1997.

Princess Diana was inescapable this year. Between actresses taking award-contending turns as her, and her son in the news for following in his mother’s footsteps and breaking royal tradition, the conditions have been ripe for a year of Diana worship. After all, 2021 has been another strange, existentially threatening 12 months; it’s unsurprising that we’d reach into the past for cultural inspiration from a different time.

Diana’s placement on a pedestal – despite being dead for almost a quarter of a century – encompasses many things about how film and TV culture works today: our new way of moralising that often ends up with the same old results, our love of reboots, and, in the case of Diana the Musical, our insistence on making absolutely anything that will look good on an “outofcontext” Twitter account, but probably not elsewhere.

She makes for the perfect 2021 subject – both familiar and beloved, with a distinctive personality and mannerisms (see: that look), and the star of her fair share of culture-dominating moments, many of which are ripe for the reenactment, like the “revenge dress” incident only just filmed by Australian actress Elizabeth Debicki for the next series of The Crown.

But, crucially and tragically, Diana is also frozen in time. We don’t know who or what she might have become by 2021. She may have distinguished herself from the rest of the Royal Family through her tolerance and acceptance, suggesting she’d have progressed along with the times had she lived, but she also had no time to tell us for sure, or, on the other hand, to make mistakes that would be deemed cancellation-worthy by the standards of the very culture that currently exalts her.

That means we can turn her into whatever we wish, within the parameters of a myth that we already know the beats of by heart. In The Crown, she’s a sympathetic vehicle for republican viewers’ distaste for the monarchy; an avatar for society’s treatment of famous, flawed women in Spencer; and in contemporary fashion, she is a throwback style queen – small “q” – whose fashion sense can be yours for £280, brought back with a vengeance by the brand Rowing Blazers in recent months (the Queen of Style documentary on Channel 4 called her “the ultimate influencer”).

Diana worship also exemplifies Hollywood’s current obsession with remakes and reboots – the dominant narrative of our narrative, with little way out of the spiral. We see this in the constant re-dos of superhero franchises, and in the self-referential quips in place of any coherent statement in the world’s largest movie property, the Marvel Cinematic Universe. It’s in “origin stories” of characters that very few people cared about in the first place – Cruella, the upcoming Wonka – and, more and more, in the real-life narratives commandeered by movie studios, TV channels and streaming platforms vying for the clickiest content. After all, there are only so many fictional villains to be humanised, and they were already scraping the barrel with Ratched.

Two of the biggest box office movies right now feature retellings of real events – King Richard, which stars Will Smith and tells the story of the father of tennis champions Venus and Serena Williams, and House of Gucci, with Lady Gaga as Lady Gaga playing real-life killer Patrizia Reggiani – while on TV, The Crown and American Crime Story are early examples of how real stories can be turned into ratings success, largely via the novelty of star casting.

In the first few months of next year, we can expect to see TV shows based on the 2018 Anna Delvey fraud scandal (Netflix and Shondaland’s Inventing Anna) and the 1995 leak of Pamela Anderson and Tommy Lee’s sex tape (Pam and Tommy from Hulu). While biopics and TV based on true stories are nothing new, the sheer number of outlets creating content has ballooned over recent years. This makes for lucrative Oscar and Emmy bait, given how much audiences love to see famous actors transforming into characters they already know. It also means that more and more real-life events are becoming content, often with less and less time elided between the events being in the news and the glossy series or film treatment on our screens.

The most important issue with this is that these shows quickly become formulaic and boring. We know how most of this stuff ends, after all, and many of their talking points come down to gimmickry, and the new perspectives they provide on what might otherwise be received wisdom.

Sometimes this can be worthwhile. In the case of The Crown, it’s helpful to remind ourselves of Diana’s suffering at the hands of the British press and the Royal Family, particularly in light of the events of the last few years (Megxit; long-standing questions over Prince Andrew’s ties to Jeffrey Epstein, etc).

Other times, as with Spencer’s heavy-handed use of the Anne Boleyn motif, it feels incredulous, actively taking away from any sense of the real person and instead contributing to the suggestion that they are merely a vessel for whatever story needs to be told that day, by those people. And it gets even more complex when your titular protagonist still happens to be alive – in the case of Pam and Tommy, Anderson herself has expressed her unhappiness with the project in spite of its supposedly feminist-leaning reclamation of her public shaming.

It’s the kind of the situation Princess Diana faced in her own life: a fascinated media that projected both positivity and hate on to her, a public who idolised her, the admiration all but imprisoning her. I’m not saying this really to express sympathy, necessarily, though it’s clear she was a kind, troubled person crushed by forces much more powerful than herself – but more to ask how constantly filtering her life through ingénue actresses and prestige scripts is so different to the treatment she received while she was alive.

And so, our year of “reclaiming Diana” doesn’t end up feeling quite as noble as it might have originally seemed. To what end have we reclaimed her? And, perhaps most importantly, was she even ours to reclaim in the first place?

When Joss Whedon Was Our Master

For much of his critically acclaimed career, screenwriter and director Joss Whedon was an untouchable nerd god. After a series of critical and commercial failures and revelations about his personal and professional conduct, he’s diminished, a figure waiting out his time ahead of the inevitable comeback. His influence, though, has proved greater than anyone could ever have expected.

Like many young people, I first became aware of Whedon because of Buffy. A teacher I had in high school recommended the series to me, and one summer my mom and I watched all seven seasons with rapt attention. I was drawn to a story about a misunderstood teenage superheroine, like so many other fans of the cult hit series. For a short time before I went to college, I also dipped my toe into the fandom for the show on LiveJournal and Tumblr.

In that fandom, anything Whedon touched was considered gold, so much so that it took me many years to realize that I didn’t even like a lot of what he has written. Luckily, in college I met people who loved shows like Buffy and Angel like I did, but didn’t want to revere Whedon as a god. Up until cast members from Buffy and his later projects said last year that Whedon had been abusive on set, in some parts of culture, that was hard to imagine. Whedon had been able to ride his reputation as the nerd auteur into directing Avengers and Justice League; for years, a perennially popular T-shirt you’d see at any comics convention read “Joss Whedon Is My Master Now.”

While there probably aren’t many people wearing these T-shirts these days, there are at this point generations of screenwriters whom he inspired, just as he was inspired by The Twilight Zone and The Bad and the Beautiful. You don’t have to look very far to find his legacy. A huge majority of science fiction and superhero movies and TV shows have dialogue that sounds like a bad imitation of Whedon’s work. The things that once made his work distinct are now bland—in part because so much of popular culture has been made in his image, and in greater part because of the limits of Whedon’s imagination.

Right now, Whedon’s career is a mess, given high-profile allegations of abusive behavior towards his cast members going as far back as Buffy the Vampire Slayer. His ex-wife also penned an article describing the ways in which his self-professed feminism was hypocritical—among other things, she said that he cheated on her for years. Previously, feminist organization Equality Now gave him an award in 2006—presented by Meryl Streep—for his efforts as a male feminist.

The invention of the myth of Joss Whedon, Nerd Master and progressive feminist, didn’t happen overnight. It took years of cult hits and near misses, as well as an obsessive fandom.

Whedon went to Wesleyan in the mid 1980s, graduating in 1987. A third-generation television writer (his father, Thomas Whedon, was one of the original writers for Captain Kangaroo and worked in children’s television), a few years after graduation he became a staff writer on the sitcom Roseanne. In 1991, he sold his script for a feature called Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which was modestly successful upon its release the following year, and began working as a script doctor and screenwriter in Hollywood, earning a 1995 Oscar nomination for his script for Toy Story.

Whedon returned to television for a Buffy series in 1997, on which he acted as showrunner. While the show was always critically acclaimed, it was also an underdog in the ratings throughout its run—replicating, conveniently, a pattern established by such seminal nerd fare as Star Trek. Its status as a cult hit also coincided with the emergence of internet fandom, and the fandom for Buffy would eventually blossom into academic scholarship about the show. This built-in fan base would follow Whedon from show to show, as he spun Buffy off into Angel in 1999, and then developed Firefly for Fox in 2002.

At the time, modern fandom was just coming into its own. While people like the Star Trek fans who circulated zines of fanfic had always obsessively watched television and formed communities around it, Buffy’s fandom coincided with new access to the internet. Unlike showrunners for The X-Files, another early internet fandom community that was threatened with cease and desist letters from Fox for fanfiction, Whedon more or less allowed Buffy fans to thrive. It was certainly clear that Whedon was aware of the fandom, its expectations, and its devotion to the show, and viewed it as an asset rather than a liability or embarrassment. When another of Whedon’s shows was under the threat of cancellation, Whedon’s then-wife reached out to members of the fandom for their help.

You can immediately identify a Joss Whedon project, and not because it has any particular look or feel.

Especially because Whedon’s television projects tended to be critical darlings that struggled in the ratings, Whedon was perceived as an underdog. His shows, with their erudite characters, were considered smart. Shows with lead female characters like Buffy Summers, who had the realistic struggles of a teenage girl while also being capable and self-assured, were rare when the show came out. Shows like Veronica Mars and Dead Like Me, concerned with equally plucky gangs of precocious teenagers with a genre fiction twist, took an obvious influence from Buffy, just as it took influence from such predecessors as Heathers.

After Buffy, Firefly was Whedon’s next major creative project. The 2002 series, about a crew of bounty hunters in a Wild West pastiche, was not as well received by Fox viewers as Buffy had been on the WB and UPN. Fox also aired the series out of order, and eventually canceled it. The movie spin off from Firefly, called Serenity, performed poorly at the box office.

Firefly was a much different show than Buffy. Rather than starring a teenage girl in high school, it starred a crew of adults in a spaceship. It was inspired by anime like Cowboy Bebop and Outlaw Star, and also, bizarrely, by the experiences of Confederate soldiers described in The Killer Angels. The show follows a ragtag group of bounty hunters who were on the losing side of a civil war and now live on the fringes of society—about as far from the world of high school as you could be.

But except for some perfunctory Western-y dialogue, where the characters’ speech is peppered with “y’all” and dropped gerunds, as well as a few phrases in broken Chinese, they don’t sound all that different from the characters in Buffy. The characters speak in catchphrases and T-shirt slogans. As Captain Mal has a heart to heart with Saffron, a conwoman who bested him, he utters the particularly groanworthy line—“I’ve seen you without your clothes on before, but I never thought I’d see you naked.”

You can immediately identify a Joss Whedon project, and not because it has any particular look or feel. Although Whedon directed two Avengers films, Serenity, one version of Justice League, and many episodes of the shows he worked on, he has no particular visual style. Most of the time, the camera is invisible and unobtrusive. He rarely uses montage or juxtaposition or even visual metaphor to portray how characters are feeling—his camera is a distant, objective observer. Even his characters are similar from show to show. Buffy’s computer nerd Willow Rosenberg is most of the template for engineering nerd Kaylee Frye from Firefly; zinger-slinging Topher Brink from Dollhouse is a dead ringer for Xander Harris from Buffy the Vampire Slayer. The thing that brings all these works together is how the characters talk, more than anything else, and focusing so much on dialogue at the expense of every other way there is of telling a story would begin to have a negative effect on his work.

After Firefly was canceled, Whedon wrote for Marvel Comics, in particular writing Astonishing X-Men, which followed up on plot points introduced in Grant Morrison’s classic New X-Men. In Astonishing, Whedon wrote mutant Kitty Pryde as the de facto main character, after long citing her as an inspiration for Buffy. It was a canny move—in addition to fulfilling what was clearly a longtime dream, Whedon was able to portray himself to his fans as an ascended fanboy, obsessed with the same niche interests they were. This was part of the reason why people would wear shirts declaring him to be their master—here was a nerd so devoted to his nerdom that he was out here making nerd shit. The culture of liking Joss Whedon was at this point already about defending him from various enemies—networks who canceled his shows, actors who he claimed said his lines incorrectly, or improvised too much. When Whedon’s Astonishing was both critically acclaimed and popular, that defensiveness only grew. Whedon was supposed to be “one of us,” and a feminist to boot. His success was a symbol of success for liberal nerds everywhere, a sign that comic books and genre fiction could be taken seriously by the world at large. If you were wrapped up in that fandom, any criticism of Whedon became an attack on everything that nerds love, and it’s a dynamic that doesn’t exist only in the past tense.

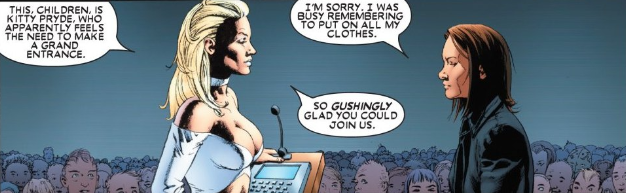

Whedon’s writing on Pryde is bizarre to read now. At the time, it was heralded as a mature take on the character, who was often portrayed as a perpetual teenager. In the first issue Kitty walks through Professor Xavier’s mansion remembering events that took place when she was a student, as if to say that she’s so much older that these events are like ghosts haunting the building. But over the course of the story she comes off as particularly immature, especially in how she talks to Emma Frost, the only other woman on the team.

X-Men nerds know that Pryde has a lot of really good reasons to dislike Frost, who kidnapped Pryde when she was a teenager. Instead of that being expressed through action, though, it is—as had become standard for Whedon by then—portrayed through particularly caustic dialogue.

When Frost complains that Pryde is late, Pryde replies that she was too busy putting all her clothes on, referring to Frost’s now-iconic costume, in which the X is a cut-out revealing her cleavage. As Frost expresses concern that students were missing from her ethics class, Pryde cracks jokes about the irony of Frost teaching ethics. In the foreground of the panel, Wolverine says, “I thought I was the one with the claws.”

Eventually Pryde makes it clear why she’s so hostile to Frost—but in a scene of dialogue. Despite one woman being able to walk through walls and the other able to turn into solid diamond and read minds, Pryde and Frost do not demonstrate their mistrust of each other, but just talk about it. The scene also doesn’t really have a lot of narrative payoff. It leads into a tease that Frost may betray the team, but despite that mistrust turning into an entire arc of Whedon’s run, she doesn’t.

Whedon’s run on Astonishing X-Men reveals his even deeper flaws as a writer relying on tried and true cliches and a desire to show off without taking any real risks. As soon as you meet a mutant student who says he’s unsure about whether or not he really wants to be a mutant but loves to fly, you know something bad is going to happen to this guy. In a few issues, he loses his powers and then dies by suicide. Beast has a bizarre storyline in which he comes out as gay, but is actually just pretending to make a woman jealous. One of the worst signs of things to come occurs in the first issue, where Scott Summers explains why they must reunite as a superhero team.

“Time to make nice with the public, eh Summers?” Wolverine asks.

“We have to do more than that, Logan,” Scott says. “We must astonish them.”

While that’s something that makes for a satisfying end-of-issue splash page, it’s simply not something anyone would ever say. People very rarely use the verb “astonish” in any context. Given that the word is on the title of the book, it has the effect of making the characters look like cyphers that are being puppeted around by an author, rather than whole people. Whedon oh-so-cleverly arranged the plot and character beats so that Cyclops would implore them to be Astonishing X-Men. Do you get it?

Image Source: Astonishing X-Men

Although Whedon continued to work in comics and television throughout the 2000s, his career had a resurgence in the 2010s. Whedon co-wrote Cabin in the Woods with longtime collaborator Drew Goddard, who directed. The film was critically acclaimed, specifically for its clever storytelling and the banter of its characters.

While Whedon had been up until this time a critically acclaimed genre writer and director, Cabin In The Woods marked the change from cult success to mainstream success. The film earned $66 million at the box office against its budget of $30 million. Despite having worked exclusively in the genre fiction trenches, Whedon was getting the mainstream critical accolades that longtime fans believed he deserved. In particular, critics like Roger Ebert and Rolling Stone’s Peter Travers praised the film’s intelligence and humor.

“The Cabin in the Woods has been constructed almost as a puzzle for horror fans to solve. Which conventions are being toyed with? Which authors and films are being referred to? Is the film itself an act of criticism?” Ebert wrote in a three star review. “With most genre films, we ask, ‘Does it work?’ In other words, does this horror film scare us? The Cabin in the Woods does have some genuine scares, but they're not really the point. This is like a final exam for fanboys.”

Whedon was then tapped to direct Marvel’s The Avengers for Marvel Studios, then a huge gamble on an untested concept. It was the highest grossing movie of 2012, and is the third highest grossing film of all time.

Whedon would also direct Avengers: Age of Ultron, but had issues working with Marvel during production. Joss stopped working with Marvel afterward, and Marvel Studios and its parent company Disney would give the franchise to the Russo Brothers. When DC was having issues with their Zach Snyder-directed Justice League films, Whedon was brought in for reshoots in 2017. His cut of Justice League was critically panned and lost money for the studio.

Whedon’s last project to date came out after his career had all but fallen apart. Ray Fisher, who played Cyborg in Justice League, said in July 2020 that Whedon had been abusive on the set of Justice League. After he spoke to the press about his experiences in April, 2021, his account was supported by his co-star Gal Godot, who said that he had been similarly abusive to her. Several cast members from Buffy would also come forward about Whedon’s behavior. The Nevers, Whedon’s new show for HBO Max, premiered in April 2021 as well, but Whedon had already been taken off the project.

While there is more The Nevers coming, the work scrapes the bottom of the barrel for Whedon. It is absolutely not an exaggeration to say that the show is X-Men in the Victorian Age; it is a show about human beings gaining mutant powers in the Victorian Age (an idea already explored by actual X-Men comics as well as Alan Moore) and then creating a superhero team to fight prejudice.

Image Source: HBO/Keith Bernstein

In the pilot you can watch him cannibalize his own, already derivative ideas in real time. The villain, a woman named Maladie, speaks in the same cadences as Drusilla from Buffy. One of the characters is a wacky inventor, similar to Firefly’s Kaylee Frye, herself an echo of Willow Rosenberg. Lavinia Bidlow, the wheelchair-using benefactor of the Victorian X-Men, is played by an actress from Whedon’s Dollhouse, where she also played a morally ambiguous matriarch.

Looking at all his work from a distance, it’s hard to imagine any of it resembling each other. Whedon jumps through genres and creates new worlds with each project. But if you’ve seen one his productions, especially his most acclaimed offerings like Buffy and The Avengers, you’ve essentially seen them all. You’ve also essentially seen a lot of work done by people who aren’t Joss Whedon.

Whedon’s work is clearly inspired by screwball comedies, which are dialogue-heavy and often derived from plays. These are movies where characters stand around talking, because the comedy is based largely in dialogue. The pleasures of Arsenic and Old Lace come from the idea that Mortimer Brewster, played by Cary Grant, is clever enough to roll with the increasingly absurd punches.

This style of dialogue, where information is delivered at a rapid pace, as back and forth quips, is essential to how Whedon writes character. In Buffy, you learn a lot about Buffy, Xander and Willow’s economic backgrounds based on how they talk. While Xander and Willow can have a complete conversation in references to nerd touchstones , Buffy uptalks, creates slang on the fly like “slayage,” and typically sounds closer to a Valley Girl than the other denizens of Sunnydale. In fact, in the series premiere, Buffy shares more in terms of how she speaks with popular girl Cordelia Chase than resident nerd Willow Rosenberg.

Given that a lot of this comes from movies adapted from plays, these lines are also often delivered in a casual, conversational tone, as if the characters are indeed the smartest in the room. It’s heightened dialogue in a heightened universe, but delivered with familiar and relatable inflections. These are the kinds of characters that match an audience of nerds’ self image, as the ones who may be low on the social totem pole but are smarter than their peers. This was a way of being a nerd that was popularized in the 1980s by movies like Revenge of the Nerds, where the jocks may be kings in high school, but the nerds end up on top eventually because of how smart they are.

Movies like His Girl Friday create situations where the dialogue can also inform the relative social standing of characters. Hildy Johnson, played by Rosalind Russel, is able to connect to a source that enters the press room to scold male reporters for dismissing her. As the other male reporters use their wit to make fun of this woman, Hildy listens to her and writes down what she’s saying. The men in the room quip at each other until she starts to get so frustrated she yells and starts to cry.

“They ain’t human,” she cries out as Hildy finally takes her by the arm and leads her out of the room.

“I know, they’re newspapermen,” Hildy replies.

At his best, Whedon uses dialogue in the same manner as His Girl Friday and Arsenic and Old Lace—as a way to deliver information about characters, their relationship to each other, and how they think about the world and themselves. It’s why people end up memorizing their favorite lines from Buffy. I still think the way that Seth Green says “Did anyone else just see that guy turn to dust?” when his character Oz sees Buffy slay a vampire for the first time is a miracle of comedic timing.

At his worst, though, this mode of dialogue is not just incongruous with the story he is trying to tell; as a viewer you start to feel like the behavior of characters is dependent on the words Whedon wants to put into their mouths. In Avengers, Captain America and Tony Stark clash throughout the first third of the movie, which is primarily about people standing around in rooms talking to each other. Although their behavior is explained away by a science fiction phlebotinum, the ways in which Steve and Tony argue with each feels out of place.

It’s not just the characterization of Steve as someone who loves rules and procedure, something that the Marvel Cinematic Universe largely abandons after this film, but that Steve and Tony don’t really express their animosity except through zingers. We are not shown that they’re different from each other, how they respond to threats differently, or how their ideals express themselves through their character. They kind of just talk about it, in a movie about human beings with the power of gods. This doesn’t build character. It tells the audience what the writer thinks about these characters without actually showing them those qualities.

All of Whedon’s worst qualities as a writer come together in a phrase that my friend Meg coined long ago: It sounds like a writer wrote this. All things are written by writers of course, but some writers really want you to know that they are capital-W writers. It isn’t enough for Whedon to write a show about plucky space freelancers in Firefly—he must also have its finale reference Sartre. Overall, it makes the work feel tortured, laborious, and very clearly designed by someone. It’s like a funhouse mirror of auteurism, where the work has a highly identifiable authorial voice because everyone is talking like a clown.

Because the point of the work is to showcase Whedon’s writing, it chokes everything else. The actors’ performances, the staging, the costuming, and especially in Avengers the craft of filmmaking itself grinds to a stop whenever a character is saying something the audience is supposed to hear.

Whedon’s status as an outsider made good gave him a level of outsized importance to a lot of nerds. It’s no surprise that some of these nerds ended up working in film and television as well. Whedon’s influence has left an indelible mark on the television landscape, given than he came at a time when genre fiction shows hadn’t yet been given the prestige TV treatment. While Buffy always performed pretty well, when it was running in 1997 the most popular shows were fare like Friends and Seinfeld, three-camera ensemble comedies with little emphasis on long-term storytelling. Television shows that are both critically acclaimed and profitable now resemble Buffy more than they do Friends.

Whedon’s success both as an underdog and as the guy with the keys to the nerd kingdom has most certainly had an influence over how science fiction television and films are now written. It isn’t enough to tell a good story or have strong character—just like Whedon did in Astonishing X-Men, writers are now writing towards an imagined splash page.

A consistent compliment Whedon was given throughout his tenure was that his scripts were very smart, which is almost true.

When Tyrion says “I drink and I know things” in Game of Thrones, that line sounds far more like a T-shirt than something a person would say. Just like Whedon manipulated Cyclops, Game of Thrones showrunners Benioff and Weiss maneuvered characters like meeples on a board game set until they arrived at “Oh shit!” moments. Watching felt like playing through a bad Dungeons and Dragons campaign, where character choices don’t matter and an outcome is predetermined. There are a lot of T-shirts that say “I drink and I know things” now, but watching that scene as a part of a narrative whole has diminishing returns.

In Whedon’s works, dialogue is the primary means of moving the story forward, and bad imitations of Whedon only show how limiting that is as a storytelling technique. The much-maligned live-action remake of Cowboy Bebop had a Whedon-y quality to its dialogue that held the show back in this exact fashion. The original show, inspired by noir stories and the French New Wave cinematic movement, let characters not say exactly what they mean, sometimes sitting still in an awkward silence. The way that they talk is a part of how they show the audience what kind of a person they are. In the remake, they just tell you. The tension between who they say they are and who they really are inside evaporates.

A consistent compliment Whedon was given throughout his tenure was that his scripts were very smart, which is almost true. I don’t know that his overall plotting was ever consistent enough to be smart, but often his wordplay and sense of irony made Whedon’s work feel very clever. You could tell there was an intelligent mind pulling strings behind the scenes, making each puzzle piece fit into each other. At its best, it’s a conversation between the audience and the creator. When the work doesn’t come together, that sense of there being someone behind the scenes is exactly what drags it down.

Whedon at his absolute worst comes across as someone who really wants you to find him clever. But stories aren’t about how smart the storyteller is. They’re about letting the audience disappear into a world you created. Joss Whedon’s ultimate flaw is that he didn’t want to disappear into the work—he wanted everyone to know who was master of his little worlds.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK