What Monks Know about Focus

source link: https://www.millersbookreview.com/p/jamie-kreiner-how-to-focus

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

What Monks Know about Focus

It’s Never Been Easy to Battle Distraction. Reviewing Jamie Kreiner’s New Translation of John Cassian in ‘How to Focus’

Books are a waste of time. So says Richard Hanania in “The Case Against (Most) Books.” He allows that books of historical interest and those by contemporary thought leaders might be valuable, but the vast majority of everything else on the shelf is worthless, especially old books. That’s correct: The classics are garbage.

I’ve addressed Hanania’s argument before but return now to note that the best rebuttal are the classics themselves. To that end I offer you How to Focus: A Monastic Guide for an Age of Distraction, which serves up several choice selections from John Cassian’s fifth-century monastic guide, the Conferences, as edited and translated by Jamie Kreiner.

The subject of monks struggling to maintain focus represents familiar ground for Kreiner, a professor of history at the University of Georgia. Last year I reviewed her book, The Wandering Mind: What Medieval Monks Tell Us about Distraction.

In that book, Kreiner explores the monastic enterprise from late antiquity through the Middle Ages across Europe and the Near East to see how monks managed intense concentration while battling interruptions and distractions. In contrast, with How to Focus she narrows the scope to just one remarkable text, refreshed for modern readers.

Ask the Desert

Cassian wrote his Conferences as an older man looking back to a period of youthful experimentation and adventure.

In his twenties, he and his friend Germanus joined a monastery in Bethlehem. The two became fast friends, “inseparable bunkmates,” of such shared intensity and interest “everyone remarked on the equality of our companionship and our sense of purpose. They said that we were one mind and soul in two bodies.”

The pair wanted to know all the ins and outs of their discipline and decided to travel beyond their local confines to hear from reputed monastic masters. So, for the next decade and a half they traveled the Nile Delta, interviewing the men known as the Desert Fathers, those in monasteries as well as hermits living on their own.

They asked a million questions. The final word count of Cassian’s Conferences stands at 150,000 words, a remarkably large book for the time. How to Focus, as Kreiner notes, represents less than 10 percent of that total with her selections geared toward, as the title suggests, the conversations dealing with attention and distraction.

And just what would monks know about that?

Minds Always Moving

We’re so attuned to our own crises and challenges, we tend to think of them as purely contemporary concerns—especially when we externalize our difficulties and blame our tools, the times, and the like. Desert monastics didn’t have Instagram; ergo, they didn’t have attentional problems.

Au contraire. While technology has evolved in the last fifteen hundred years, the human brain has not. And few people in the ancient world cared as much about the challenges of attention and distraction as monks. Our reasons might differ today, but we have much to learn nonetheless.

A repeated complaint from Cassian and Germanus is the difficulty maintaining focus on their prayers. “The mind is always moving and meandering, and it’s torn apart in different directions like it’s drunk,” says Germanus at one point. “It doesn’t even have the power to hold onto or stick with things it finds entertaining!”

Unfortunately, knowing focus matters fails to engender concentration. “What we know hasn’t helped us attain the steady and stable clarity we’ve been seeking,” he says. “Even when we feel our heart heading straight toward its goals, the mind imperceptibly turns the other way. . . .”

Germanus directed this second comment to Abba Serenus of Scetis, who responded, “The nous or mind is defined as aeikinētos kai polykinētos, always and very much on the move.” You might recognize our word kinetic in the Greek. This bubbling, jumping, flitting mind can only be tamed by training through meditation, memorization, fasting, and other forms of ascetical effort by which “it will become strong enough to drive off the enemy’s stimuli. . . .”

It’s a bit of a relief to realize, no? Why does the mind meander? Because that’s what minds do.

Thinking about Thinking

Monks attempted the radical and difficult practice of pure prayer, to bring their entire mind to bear on the act. Given their intense interest in concentration, and also being prone to endless disruptions in the effort, monks became experts in what we today call metacognition—thinking about thinking.

“It is impossible for the human mind to empty itself of all thoughts,” says Abba Nestorus, a hermit interviewed by Cassian and Germanus. The question is what kind of thoughts to entertain? Nestorus advises the pair to immerse themselves in sacred reading. “Do it continually—or better, nonstop!—until that constant recitation and reflection saturates your mind and shapes it into a kind of likeness of itself.”

Nestorus offers three reasons, the third the most profound. First, when a person is engrossed in literature, the mind can stay attuned to its content instead of “toxic thoughts.” Second, an understanding of the text comes not only while reading, but also when we take those thoughts with us into other mental states. We’re able to reflect on what we’ve read when we’ve turned out attentions elsewhere, even when we go to sleep.

Another interviewee, Abba Isaac, also talks about this tricky feature of mental latency, though regarding prayer, not reading. “We should,” he says, “be the sort of person we are in prayer before it’s time to pray. After all, our state of mind during prayer is unavoidably shaped by the situation prior to the moment.”

Attention researcher Gloria Mark—a modern scientist, not a monastic—would affirm Isaac’s point. When we approach any task, as Mark notes in her book, Attention Span, we do so by constructing cognitive frames that marshal the various mental resources required for the activity. When distractions occur, we change frames mid-action. The frustration we feel in getting back on task involves the difficulty in reassembling the cognitive frame we enjoyed prior to the interruption.

Since our mental states persist from one moment to the next, Isaac encourages Cassian and Germanus to hold onto their desired state by preparing for it in advance. It’s a way of ensuring our cognitive frame is strong enough to resist distraction and an approach that applies to a wide variety of intellectual activities.

I mentioned three reasons from Nestorus for immersive reading but have so far only covered two. What of the third and most mysterious of his reasons?

Changing Our Minds

Nestorus’s third and most mysterious reason for immersive reading is that sustained engagement deepens our understanding of what we read by the changes wrought in ourselves through the very process of reading.

“How the scriptures look depends on what the human senses are capable of,” he says. “As our mind is gradually remade through this sustained effort, the shape of the scriptures begins to be remade, too, and it’s as if the beauty born of this more sacred perceptiveness grows as we grow.”

Our investment in reading changes the book because the book has changed us. And this is where Hanania’s argument fundamentally falls short. If books are merely a means of transferring information, then perhaps, yes, a book is a waste of time. If a summary of its thesis and key points could be presented in a brief article or Substack post, why not just save the hours and read the Substack post? All the more if the information is outdated or questionable for one reason or another.

But that mistakes what a book is for. A book is a tool. It’s a machine for thinking. And “all machines,” as Thoreau once said, “have their friction.” The time it takes to engage with ideas—whether factual or fictional, emotional or intellectual, accurate or inaccurate, efficient or inefficient—might strike some as a drag. But the time given to working through those ideas, adopting and adapting, developing or discarding, changes our minds, changes us.

It’s not about the wisdom we glean. It’s about what wisdom we grow.

What about that more basic plane upon which we engage a book, the information itself? After all, if the book is ancient, is the information even useful? Can the ideas shared in distant philosophical or spiritual contexts translate with any value to our present, secular world? Though the answer depends entirely on the ends to which we put the information, Cassian’s book offers us an answer here as well.

The Goal of Reading

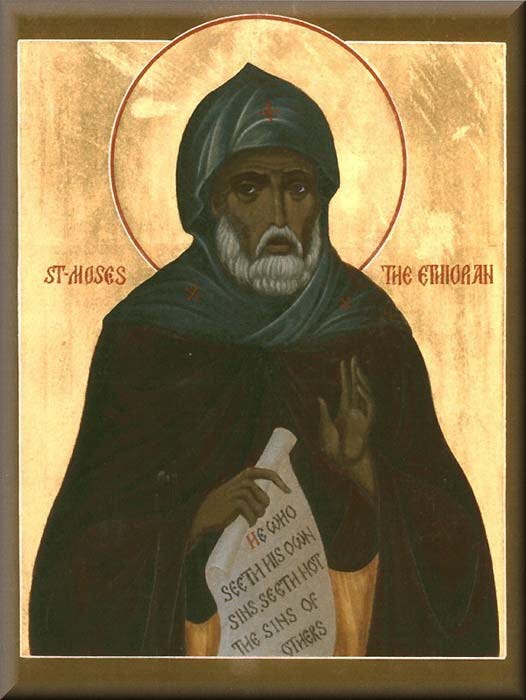

In the first chapter of the Conferences, Cassian and Germanus visit Abba Moses of Scetis, known to the faithful as St. Moses the Black or St. Moses the Ethiopian, whom they regard as “the sweetest of all those extraordinary flowers” in the desert. They ply Moses with the same sorts of questions they later asked of other fathers: Why is the monastic life so difficult? Curiously, Moses addresses their pleas by talking about short- and long-term goals.

“Every acquired skill and every discipline,” says Moses, “has a scopos and a telos, some immediate goal and some ultimate goal that is particular to it. Practitioners of any skilled craft will gladly and good-naturedly work through all their fatigue and risks and costs as they keep those goals in mind.”

Moses develops the idea from there and, as someone who professionally spends a lot of time reading modern goal-achievement literature, I can say that his treatment is every bit as useful as the work of scholars working today. Moses’s argument can even help resolve the question of whether we should read the classics.

If you’re Richard Hanania, no. You don’t possess a telos that would justify the effort. But if you see classics such as John Cassian’s Conferences as valuable, then most definitely yes. And Jamie Kreiner’s presentation in How to Focus represents the perfect scopos. Pick it up and enjoy the thoughts it helps you conjure.

Thanks for reading! If you enjoyed this post, please hit the ❤️ below and share it with your friends.

Not a subscriber? Take a moment and sign up. It’s free for now, and I’ll send you my top-fifteen quotes about books and reading. Thanks again!

Make sure you also read . . .

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK