Venture Capital & Free Lunch

source link: https://www.notboring.co/p/venture-capital-and-free-lunch

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Venture Capital & Free Lunch

Why Venture Capital is the Best Asset Class

Welcome to the 68 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last week! If you haven’t subscribed, join 220,300 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Range ETFs

Did you enjoy Season 1 of Age of Miracles and now want to invest in the growing nuclear energy market? The Range Nuclear Renaissance ETF is your gateway to the clean, safe, and ever-expanding world of nuclear power.

If you didn’t listen to the pod, here’s a quick summary of why we’re so bullish on nuclear:

Clean: Nuclear energy emits zero greenhouse gasses

Safe: Don’t buy into the stigma, nuclear is one of the safest energy sources in the world.

Reliable: Nuclear power plants deliver 24/7, always-on electricity, providing the backbone of stable grids.

The Range Nuclear Renaissance ETF offers:

Nuclear Energy Diversification: Gain exposure to a diverse range of companies across the nuclear energy spectrum.

Growth Potential: The nuclear energy industry is likely poised for expansion, driven by ambitious climate goals and rising energy demands.

Liquidity and Convenience: Trade the ETF easily on major exchanges, enjoying the flexibility and transparency of a publicly traded instrument.

Don't be left in the dark. Invest in the Range Nuclear Renaissance ETF today and illuminate your portfolio with the power of clean, safe, and reliable nuclear energy.

Hi friends 👋,

Happy Tuesday!

Optimism is in the air, and so am I. I’m sending this from 32,000 feet up on my way out to California to meet with companies building satellites, Von Neumann universal constructors, cultivated meat, hydrocarbons made with CO2 and nuclear, and more. All of these outlandishly ambitious ideas have been funded by venture capitalists.

Last week, Nadia Asparouhova made the case that tech is starting to stick up for itself again. You know who no one’s willing to stick up for, though? The venture capitalists.

Let’s get to it.

Venture Capital & Free Lunch

Venture capital gets a lot of shit, but I’m here to tell you that venture capital rocks.

In fact, it’s the best asset class there is.

I can hear the other asset classes yelling at me. Certainly, some have a case:

Public equities are the largest

US Treasuries are the safest

Real estate is the only one you can live in

Private equity is an asset class.

But there is no more beautiful asset class than venture capital.

Venture capital is a free lunch machine.

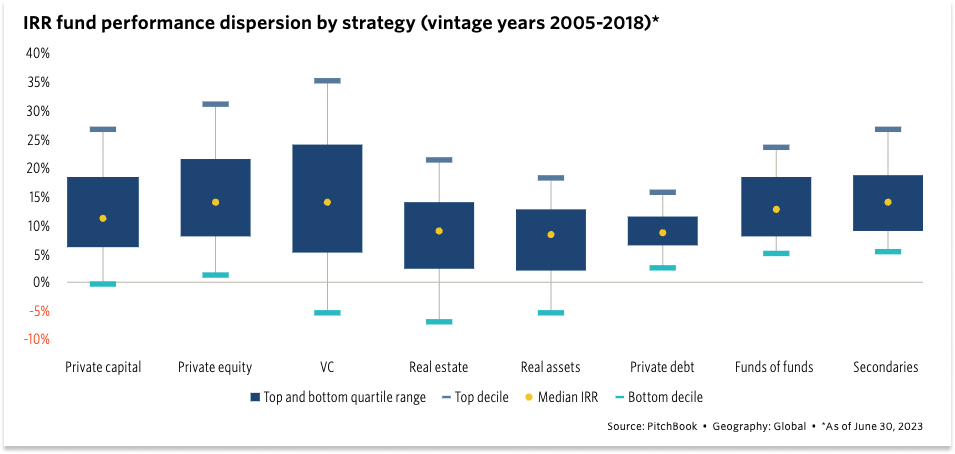

I’ll admit that venture capital isn’t perfect. It’s risky, illiquid, and highly variable. The best venture funds perform amazingly well; the worst ones are horrendous.

Even the best venture funds are wrong much more often than they’re right. Peter Lynch said of public markets investing, “In this business if you’re good, you’re right six times out of ten.” In venture capital, if you’re good, you’re right maybe three times out of ten, possibly twice, probably once, but when you’re right, you’re really right.

Therein lies the beauty.

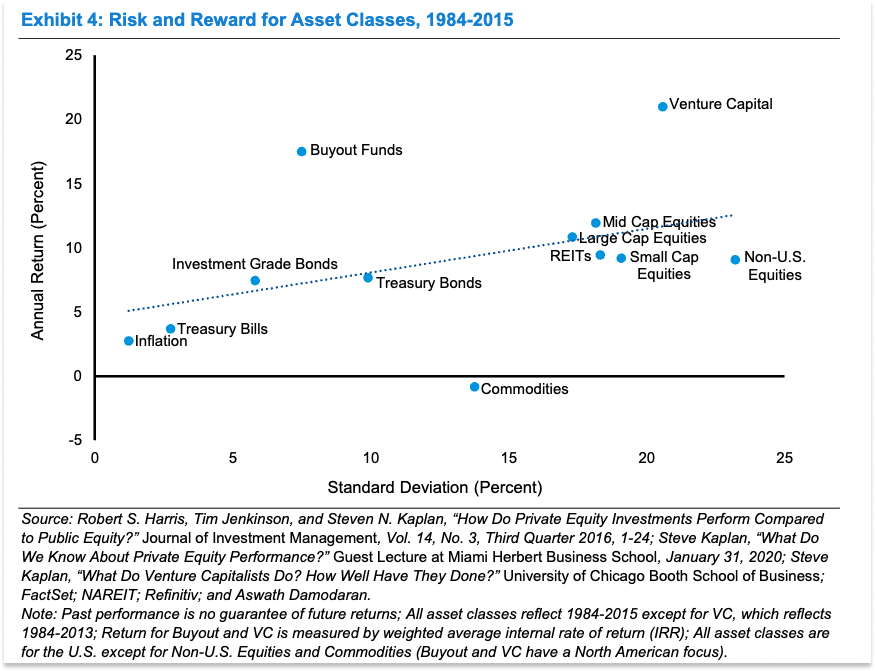

No asset class’ constituents fail at a higher rate than venture capital’s, yet venture capital’s returns match or exceed all the others’.

Think of the dumbest fucking investment your least favorite venture capitalist has made. FTX, WeWork, Quibi, Juicero, Theranos, pick your poison. Choose all of them, if you’d like. Sprinkle in some Clubhouse, the 9,000th dating app, the 78,000th social network, the 19th best foundation model company, the 10,000 PFP NFT project.

All of those screaming zeroes are included in these returns:

The data isn’t super clean. Depending on the time horizon and whether you’re talking risk-adjusted returns, venture capital may or may not be the best performing asset class. And investing in venture capital requires locking your money up for a decade, unlike stocks or bonds which you can go sell right now.

But the fact that venture capital is even in the running, and wins on some time horizons, means that the world gets all of that innovation – from failures and winners alike – for free.

There is no such thing as a free lunch, except, perhaps, when it comes to venture capital.

Free Lunches

This doesn’t mean that venture capitalists are smarter than anyone else. As I mentioned earlier, they’re wrong a lot.

What it does mean is that venture capital, with its Power Laws, is the asset class best designed to embrace variance.

Would returns look better if VCs simply funded the good companies and didn’t fund the bad ones? Maybe in the short-term, maybe not in the long-term, but it’s a moot point, because no one knows what the great ones are going to be ahead of time. Venture is beautiful for embracing that.

Venture capitalists can fund the wildest ideas in the world, many of which won’t work, some of which will work bigly, and their returns as a group end up being pretty great.

And on top of that, we get the fruits of innovation, because venture capital is the only asset class that funds truly new things.

Take the current hype cycle in AI. Venture capitalists are pouring stomach churning amounts of money into foundation model companies. Billions of which will, for all intents and purposes, be lit on fire. The problem is: it’s hard to tell which billions until you put the money up and watch it play out. Venture capital is designed to put those chips on the table and see what happens.

If history is a guide, most AI companies will go to zero, and a small handful will generate enough returns to carry the rest. Those returns will go to venture funds’ limited partners, the charities, endowments, pensions, and other individuals and institutions who invest in venture funds, who will take that money, reinvest some into the next generation of venture funds, and operate their institutions with the rest.

Way back in 2007, before he became a VC himself, Marc Andreessen wrote:

The best VCs get to improve society in two ways: by helping new companies take shape and contribute new technologies and medical cures into the world, and by helping universities and foundations execute their missions to educate and improve people’s lives.

The world, for its part, may get AGI in the bargain.

It is not from the benevolence of the venture capitalist that we expect our AGI, but from their regard to their own self interest.

The Visible Invisible Hand

The invisible hand is more visible in venture capital than it is in any other asset class.

Venture is an ecosystem made up of parties acting in their own self-interest that seems to operate with some sort of collective intelligence on a longer timescale.

If you zoom in on the behavior of any one participant at any given time, you might think that they’re behaving stupidly. In many cases, they are. The ecosystem works not in spite of, but because of, the stupidity of some of its participants.

Venture capitalists are willing to fund companies creating new technologies even if those companies don’t seem to have a viable business model in sight. The best venture capitalists try to fund companies that marry new technology with viable business models, but some technologies are just too early to make any economic sense. That’s OK! There are venture capitalists willing to fund those, too.

Maybe they believe that the team is smart and will figure out a model. Maybe they hope the company will be acquired for its technology. Maybe they hope the market will catch up while the company is still a going concern. Maybe they just got really excited and bought into the hype.

It’s easy to make fun of VCs for buying into hype so quickly. My X feed is chock full of memes about VCs who went from being web3 investors to AI investors to Gundo investors faster than you can say “Patagonia vest.”

I think hype-buying is one of venture capitalists’ most endearing qualities.

Hype is usually an indicator that there’s something there, even if that something is a long ways away. As I wrote in Capitalism Onchained, “Any technology that is sufficiently valuable in its ideal state will eventually reach that ideal state.” But it takes years, sometimes decades, of winding experimentation, and millions, sometimes billions, of dollars to reach that state, or even to reach a pre-ideal state in which the technology can be built and sold profitably.

Who’s going to fund that experimentation period? A bank? The public markets? Nope. Venture capitalists.

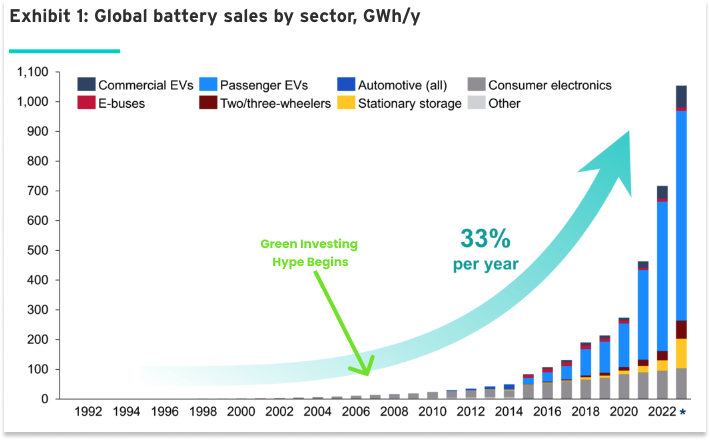

Take the clean tech bubble that Kleiner Perkins helped kick off in the mid-2000s. In 2007, Kleiner Perkins Partner John Doerr said, “Going green is bigger than the Internet. It could be the biggest economic opportunity of the 21st century.”

Kleiner and other venture capitalists ended up investing a tremendous amount of money investing in clean tech – on the order of tens of billions of dollars. They lost money on the vast majority of those investments. But their investment attracted talent to the industry and provided an incentive to improve clean technologies that helped lay the groundwork for the dramatic increase in renewable and storage capacity we’re benefiting from today, nearly two decades later. And Tesla, which at a $626 billion market cap is worth multiples of all of the money invested in clean tech.

Along with the government, which funds basic research, venture capitalists often fund too-early technologies as they take their first steps out of the lab and into the cutthroat world of the market. They provide the capital that sustains technologies through the flat-looking parts of eventually exponential curves, and often lose that capital. Then, when the curves go exponential, the next generation of venture capitalists take advantage to make investments that actually deliver returns.

That’s what I mean when I say that there seems to be collective intelligence at play on longer timescales. The opportunity to generate returns today might not exist if someone hadn’t been willing to lose money decades ago. No venture capitalist does this altruistically – they’re driven by the small, against-all-odds chance that this too-early technology might be the next big thing – but in their mistakes they create opportunity for others.

Losing money is all fun and games for VCs because it’s not their money, right?

But What About the Pensioners?

Whenever a specific investment goes south, a cry goes up for the poor pensioners, charities, and endowments who are really the ones funding all of these experiments behind the scenes.

I’m here to tell you that those pensioners are doing just fine, thank you very much.

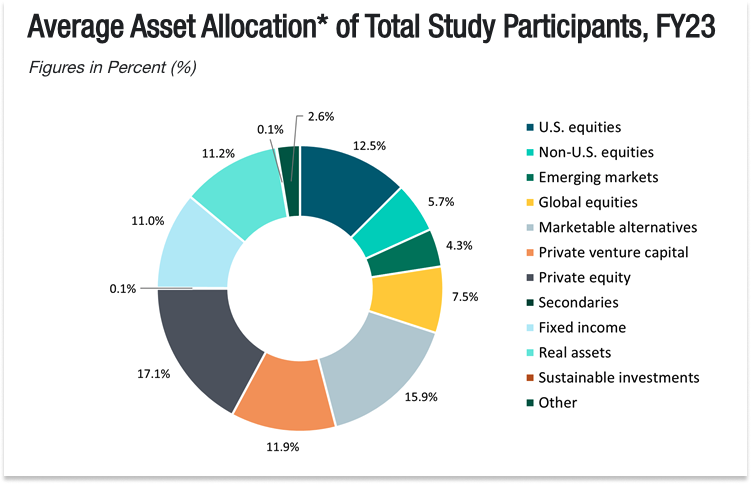

Limited Partners (LPs) often manage large pools of capital that they invest across a number of asset classes. Yale’s endowment, for example, is roughly $42 billion.

NACUBO (The National Association of College and University Business Officers) does an annual survey on endowments’ asset allocations. When Marc Andreessen wrote The Truth About Venture Capitalists in 2007, NACUBO found that endowments allocated 3.5% of their assets to venture capital. In 2023, that number grew to 11.9%.

LPs build portfolios that are diversified across asset classes, and then further diversified within asset classes. Within venture, they will invest in a number of funds, each with its own strategy: some early stage, some late stage; some generalist, some vertical. They continue to invest across vintages, meaning that every year, they’ll invest in new funds or re-invest in funds they’ve already invested in. Those funds, in turn, diversify across a number of investments that fit their criteria over a number of years.

From the LPs’ perspective, venture capital is a small but growing high-risk / high-reward piece of a much larger portfolio. If any individual investment that one (or multiple) of their venture managers make fails, no matter how spectacularly, it’s unlikely to have a big impact on the overall portfolio. What’s more important to LPs is that venture as an ecosystem continues to take the kinds of risks that have a shot at driving higher returns.

If one venture firm makes a bunch of too-early investments that lose a lot of money, that firm may go out of business, but the LP will still be around when the fruits of those too-early technologies ripen.

From their gods-eye perspective, LPs can invest in all of the messiness – the successes and the failures – and expect that on the other side, in ten or so years, they’ll get multiples of their money back. Then they’ll keep investing, and harvest the seeds sown by the previous generation’s losers.

More returns means more money to donate to charity, fund growing pensions, run universities, and continue to invest in venture capital.

The Fund Size Paradox

One of the things LPs do with those returns is continue to invest in the funds that got them there, inflating those funds’ assets under management over time.

The rise of the resulting megafunds has drawn criticism, occasionally from venture capitalists themselves, based on the argument that large funds are terrible for returns and exist to generate management fees.

Venture capital funds typically earn “2 and 20”: 2% management fees and 20% carry. They take 2% of the fund size every year for ten years to pay salaries and generally manage the fund, and they keep 20% of what they earn once they’ve paid back LPs.

The thinking behind the criticism of megafunds goes something like this: it’s harder to generate outsized returns on larger pools of capital than it is on smaller pools of capital. Owning 20% of a company that IPOs for $10 billion means a 20x for a $100 million fund, but doesn’t even return a $3 billion fund! But they don’t care, because they make 2% of a big number every year no matter what.

So if megafunds exist solely to milk fees out of LPs, why the hell do LPs definitionally invest more money in these larger funds than they do in smaller funds?

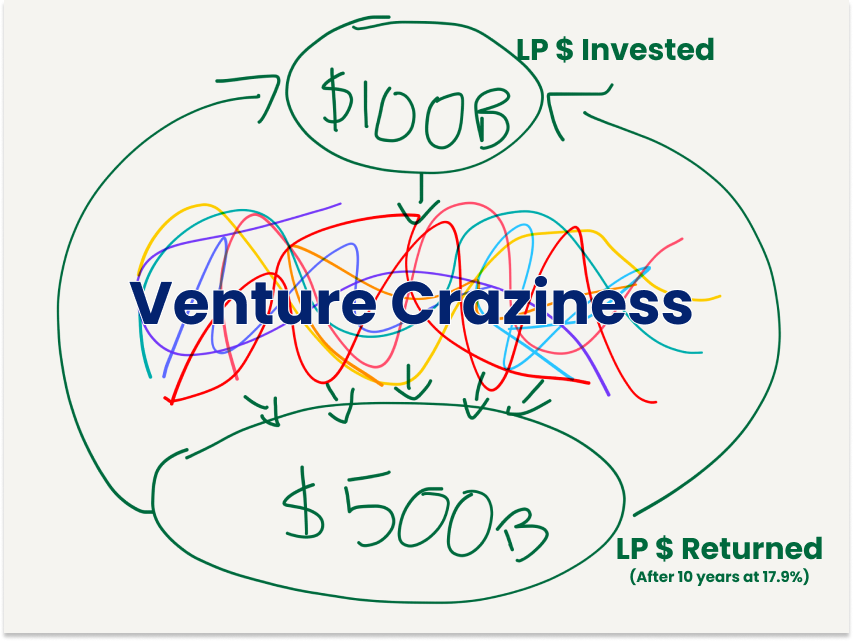

Let’s go back to this graphic:

Assume that every year, there’s a certain amount of money that’s going to get allocated to venture capital and a certain number of companies that are going to generate returns.

If all of the money that’s currently allocated to megafunds instead got allocated to smaller early stage funds, there would be a few issues.

First, those small funds’ extraordinary returns would decrease. More competition at the early stages would likely drive higher valuations and it would mean that each early stage fund would win fewer deals, decreasing the likelihood that they’ll own one of the handful of companies that matter.

Second, and more importantly, there would be less capital available downstream to fund winners. Some companies need hundreds of millions of dollars to get to the point at which they can become profitable. This was somehow true of pure software companies, and it will be increasingly true as venture capital funds more capital intensive foundation model and deep tech companies.

Without megafunds operating at the Series A and beyond, more companies would fail before they have the chance to go public, which would lower overall returns to LPs. That, in turn, would mean that small, early stage funds couldn’t take the types of risks they need to take to generate those outsized returns and give the wildest ideas a chance.

If anything, we need more megafunds. I recently spoke to one of my LPs who’s interested in deep tech investing in India, and his biggest concern isn’t the talent in the space (there’s a lot) or the market (which is growing), but the lack of downstream capital. If even the most promising companies can’t raise the capital they need, then it’s really hard to justify starting or investing in a new company.

There’s that invisible hand making itself visible again: self-interested parties dynamically evolving into an ecosystem with a robust capital pipeline. Larger firms are rewarded for playing their role in fees, smaller firms are rewarded for playing theirs in higher upside when they’re right. One is not better than the other; both are necessary.

Founders win, LPs win, and the world wins.

If megafunds win too by generating a lot of fees in the process, great! If you believe that megafunds earn too much money relative to the service they provide, make like Jeff Bezos, treat their margin as your opportunity, and go start a larger fund with lower fees or something.

An Aside on Fees

Speaking of megafund management fees, I think they’re among the most interesting buckets of capital in the world, and that we’ll see them utilized in increasingly beneficial ways.

The rationale is simple: if megafunds are confident that they’ll benefit from the growth of the early stage tech ecosystem, they can justify paying for all sorts of pro-ecosystem things. If you believe that technology is good, and I do, then management fees applied to strengthen the tech ecosystem are like charity that keeps paying for itself.

It’s unsurprising, for example, that this weekend’s Gundo defense tech hackathon was co-organized by 8VC and sponsored by a number of others, including Founders Fund, or that a16z hosted an unofficial St*****d Defense Tech Club kickoff party the night before.

Those are tiny examples. On a larger scale, a16z recently announced that it would be “supporting candidates who align with our vision and values specifically for technology.” It also built a world-class crypto research team based on the belief that “There is an opportunity for an industrial research lab to help bridge the worlds of academic theory with industry practice.” The team has since built and open sourced a number of useful research-based products, including Lasso and Jolt.

My hunch is that this is the beginning of a larger trend in which venture capital firms use their management fees, which are already netted out of the return numbers I shared earlier, to support the industries they invest in in increasingly creative ways.

For firms with a long view, there’s an economic incentive to support the kinds of things that have long, uncertain payoffs that doesn’t exist anywhere besides government and academia, both of which have become increasingly sclerotic and slow-moving. I wouldn’t be surprised to see more VC-supported basic and applied research labs, for example. In the short-term, it’s good marketing (and a good way to pull more smart people and ideas into their orbit), and in the long-term, it’s a way to increase the number of fundable companies and produce returns (and fees) on ever-larger funds.

The world gets accelerated research and knowledge in the bargain. Another free lunch. Yum.

Viva la VC

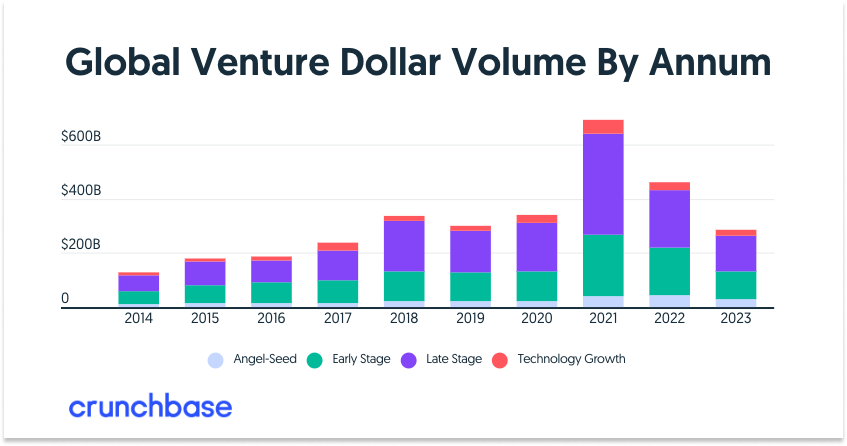

Venture capital is at a low point. According to Crunchbase, the $258 billion venture capitalists invested in 2023 is the lowest amount they’ve invested since 2017.

It’s not particularly popular, either. Certainly, VCs espousing pro-Putin views on Twitter doesn’t help, but there are a number of reasons.

VCs make money (and sometimes take credit) when other people – founders and startup employees – do all of the hard work. They have to tell founders “no, we don’t want to fund your life’s work” much more often than they get to say “yes.” They invest in brash, risky companies that occasionally fail spectacularly. They jump from industry to industry with, often, nowhere near the depth of understanding of those industries as the people who work in them. They write blogs and host podcasts 😬

And some of them are genuinely shitty: either bad investors or worse, as predatory behavior in the downturn exposed once again. They stand in the way of acquisitions that would be life-changing for founders but meaningless for returns. Often, the most helpful thing some VCs can do is write a check and get out of the way. I’ve worked with bad ones from the other side of the table and I know how harmful they can be. The good news is, over time, the market typically punishes the bad ones.

There are a ton of really great VCs as well, but I’m not here to argue that VCs are heroes. The best thing they can do is to identify, encourage, and fund the entrepreneurs who actually create value by building great things.

All I’m saying is that as an asset class, venture capital is way better than it gets credit for. There’s no other asset class that’s been as positive-sum or cooked more free lunches over the past half century.

Founders can walk into a VC’s office with an idea and a dream, and leave with millions of dollars. They’ll hire people and build things that have ever only existed in their imagination. Most of them will fail, and many of those who do will be able to walk back into those same offices and get a fresh bag of money to try again. Some will succeed, and they’ll succeed so outrageously that the value they create will pay for all of the failures and then some. They might even Make the World a Better Place™️ in the process.

I’d argue that even if venture capital underperformed other asset classes, generated 0% returns or something, it would be a net benefit to society to have a pool of capital that funds crazy experimentation. But this is capitalism, and returns are what keeps the machine humming. So the fact that VC has generated such strong returns over a long time horizon is key.

The question is: will venture continue to deliver returns?

I think the answer is undoubtedly, unquestionably yes.

Tech is Going to Get Much Bigger as tech’s total addressable market expands to include large existing industries that have been relatively untouched by technology, including industrials and agriculture. Cheaper energy, intelligence, and dexterity, in the words of Valar Atomics’ Isaiah Taylor, will mean new opportunities to attack old industries with cheaper, better products. Higher margins in large industries will make for very valuable companies. And things that were previously impossible are becoming possible at an accelerated rate.

Venture was created for times like this, when big shifts in underlying technologies create opportunities for crazy geniuses to build products that might change the world.

If anything, the past few of decades of pure software investing were a necessary interstitial period during which bits developed to the point at which they could make a meaningful impact on the world of atoms, and the next few will be the period during which the combination of bits and atoms made the world a magical place.

The speed at which change will happen, the amount of capital these companies will require, and the outlandish ambition of the projects founders will tackle will mean more and bigger blowups than ever before, but it will also mean more and bigger winners. In the process, the world will get a suite of new capabilities – medicines, machines, money, (literal) moonshots and more – practically for free.

So by all means, ape into the Gundo! Fuel that techno-optimism! Lose many, and win some. The only mistake is to play it too safe, to fund things that don’t matter.

As tech gets much bigger, venture capital will get much bigger, too. That’s a beautiful thing. God bless the United States of America, and God bless venture capital 🇺🇸

Thanks to Dan for editing!

That’s all for today! We’ll be back in your inbox on Friday with a Weekly Dose.

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK