Smuggling of silkworm eggs into the Byzantine Empire

source link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smuggling_of_silkworm_eggs_into_the_Byzantine_Empire

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Toggle the table of contents

Smuggling of silkworm eggs into the Byzantine Empire

This article or section appears to contradict itself. Please see the talk page for more information. (November 2022) |

The Silk Road | |

| Date | Mid-6th century (552/563 CE) |

|---|---|

| Location | Central Asia |

| Participants | Two monks |

| Outcome | Establishment of Byzantine silk industry |

In the mid-6th century CE, two monks, with the support of the Byzantine emperor Justinian I, acquired and smuggled living silkworms into the Byzantine Empire, which led to the establishment of an indigenous Byzantine silk industry that long held a silk monopoly in Europe.

Background[edit]

Silk, which was first produced sometime during the third millennium BCE by the Chinese and/or Indus Valley Civilisation,[1] was a valuable trade commodity along the Silk Road.[2] By the first century CE, there was a steady flow of silk into the Roman Empire.[2] With the rise of the Sassanid Empire and the subsequent Roman–Persian Wars, importing silk to Europe became increasingly difficult and expensive. The Persians strictly controlled trade in their territory and would suspend trade in times of war.[3] Consequently, the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I tried creating alternative trade routes to Sogdiana, which at the time had become a major silk-producing centre:[4] one to the north via Crimea, and one to the south via Ethiopia.[5] The failure of these efforts led Justinian I to look elsewhere.

565AD. Byzantine Empire, blue and purple; Sassanid Empire in yellow. Sassanid vassals, in orange, encompassing the Persian Gulf to the south, and reaching the Indus river in the southeast and the Kingdom of Khotan in the northeast (both silk-growing areas).

Sogdiana, located in Central Asia north of the Sassanid states. Silk was also produced in the Kingdom of Khotan (east of Sogdiana) at this time, and in the Indian subcontinent, east of the Sassanid Empire

Silk production also occurred in these areas of East Asia in 560AD, in the Northern and Southern dynasties or Six Dynasties period

Expedition[edit]

Two unidentified monks (most likely members of the Nestorian Church[2][5]) who had been preaching Christianity in India (Church of the East in India), made their way to China by 551 CE.[6] While they were in China, they observed the intricate methods for raising silkworms and producing silk.[6] This was a key development, as the Byzantines had previously thought silk was made in India.[clarification needed][7] In 552 CE, the two monks sought out Justinian I.[5] In return for his generous but unknown promises, the monks agreed to acquire silkworms from China.[clarification needed][4] They most likely traveled a northern route along the Black Sea, taking them through the Transcaucasus and the Caspian Sea.[8]

Since adult silkworms are rather fragile and have to be constantly kept at an ideal temperature, lest they perish,[9][clarification needed] they used their contacts in Sogdiana to smuggle out silkworm eggs or very young larvae instead, which they hid within their bamboo canes.[clarification needed][8][5]Mulberry bushes, which are required for silkworms, were either given to the monks or already imported into the Byzantine Empire.[8] All in all, it is estimated that the entire expedition lasted two years.[10]

Impact[edit]

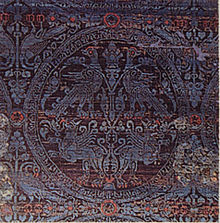

Shortly after the expedition there were silk factories in Constantinople, Beirut, Antioch, Tyre, and Thebes.[5] The acquired silkworms allowed the Byzantine Empire to have a silk monopoly in Europe. The acquisition also broke the Chinese and Persian silk monopolies.[8] The resulting monopoly was a foundation for the Byzantine economy for the next 650 years until its demise in 1204.[11] Silk clothes, especially those dyed in imperial purple, were almost always reserved for the elite in Byzantium, and their wearing was codified in sumptuary laws.[2] Silk production in the region around Constantinople, particularly in Thrace in northern Greece, has continued to the present (see: Silk museums of Soufli).

In popular culture[edit]

In Season 1, Episode 4 of the Netflix series Marco Polo,[12] released in 2014, two men are caught smuggling silkworms in their walking sticks. Kublai Khan must decide whether or not to kill them for their crime, which is punishable by death, but he ultimately shows mercy and allows Marco Polo to decide their fate.

Sources[edit]

- ^ Good, I. L.; Kenoyer, J. M.; Meadow, R. H. (June 2009). "NEW EVIDENCE FOR EARLY SILK IN THE INDUS CIVILIZATION". Archaeometry. 51 (3): 457–466. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.2008.00454.x.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Silk". University of Washington. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Norwich, John (1988), Byzantium: The Early Centuries pg. 265

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clare, Israel (1906), Library of Universal History: Mediaeval History pg. 1590

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Norwich, pg. 266

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clare, pg. 1589

- ^ Clare, pg. 1587

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Patrick Hunt. "Late Roman Silk: Smuggling and Espionage in the 6th Century CE". Stanford University. Archived from the original on 26 June 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ "The Smithsonian on Silk Production". Archived from the original on September 27, 2009.

- ^ "History of Silk - The Silk Museum". Archived from the original on 21 May 2021.

- ^ Muthesius, Anna (2003), Silk in the Medieval World pg. 326

- ^ ""Marco Polo" The Fourth Step (TV Episode 2014) - IMDb" – via www.imdb.com.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK