Creating a Blackout Poetry Art Show

source link: https://medium.com/write-wild/creating-a-blackout-poetry-art-show-d0ee57828398

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Poetry

Creating a Blackout Poetry Art Show

How I Wrote 22 Giant Blackout Poems in 3 Weeks

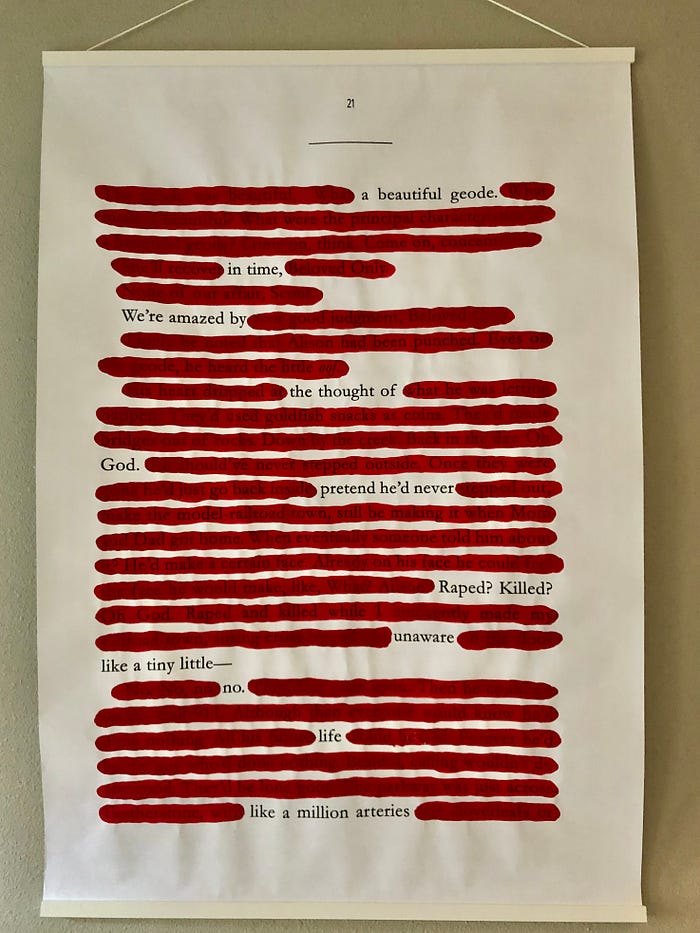

A giant blackout poem. Text: The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

“Every new idea is just a mashup or remix of one or more previous ideas.” — Austin Kleon, Steal Like an Artist

A few years ago, I started experimenting with blackout poetry. Blackout poetry, sometimes called “erasure” poetry, is where the writer uses an existing text and “blacks out” or “erases” words on the page in order to create a new poem. The words that remain after the erasure form the poem.

How to Make a Blackout Poem

1. Choose a text

2. Black out or erase words

3. What remains is a poem

Blackout poetry is a type of Found Poetry. Found poetry is an umbrella term encompassing any poem that uses an outside source text to create a new poem. That text is generally previously published material, although simply using this definition doesn’t exactly hit the nail on the head, as non-literary texts also work well for found poems. (Examples include manuals, informational packets, advertisements, and other texts not meant to be defined as literature.)

Essentially any poet who uses material that is not wholly original to create a new poem is engaging with found poetry. (This may also include poets using their own past texts — old journals as an example.) Found texts may include but are not limited to: Newspapers, books, periodicals, graffiti, other poems, street signs, advertisements, propaganda, online media, Twitter posts, or anything with words that can be rearranged, erased, cut-out, or reformulated to create a new and wholly original piece of poetry.

I got interested in blackout poetry because it is a form of resistance against problematic texts.

One of the first blackout poems I ever published (In Crab Fat Magazine) was created using a short story by H.P. Lovecraft, “In the Mountains of Madness.” This was 2016. It was before Lovecraft Country came out. We were in the midst of the 2016 election. I felt powerless about the sexism I saw in literature and in the world.

Erasure of HP Lovecraft “In the Mountains of Madness”

Much has been said about Lovecraft’s racism, but I always noticed less discussion of his misogyny. Lovecraft considered himself a “puritan” regarding sex and portrayed women as purely sexual animals. Many researchers believe he was terrified of women.

I became fascinated with exploring the work of male authors through erasure. I made a trip to a local used bookstore and bought about 20 used paperbacks, purely for the purpose of taking them home and ripping out the pages to cover them in sharpie.

Amusingly, the clerk at the bookstore was delighted by my book choices. “I love all these writers,” he told me, as I bought a stack of the most problematic, sexist, and well-taught male authors in literature.

When I make an erasure poem, I try to find pages in a book with certain words I’m interested in. I sometimes do a word search in the ebook or public domain version of a book online to find certain words. I started looking at how classic male authors portray women.

Erasure has been called deconstruction, excising, and mutilation. But I’ve found more joy in discovering that an author’s words are not what they seem than I have in taking them apart clinically, piece by piece. By which I mean, hopefully, by engaging with a text, you will have a new understanding of that text.

I learned from these early erasures that not all male authors are what we are led to believe. For example, Ernest Hemingway is often considered the “man’s man” of writing. His work is supposed to be concise and clear, a “hallmark” of manly writing.

But I found Hemingway to be surprisingly soft. His books are full of ephemeral descriptions and stream-of-consciousness passages that ask the reader to delve into a dream. Hemingway is drenched in emotion.

There is a physicality to erasure. It asks you to touch words, rearrange them, skim like a reader, and find meaning like a poet. The key here is connection. If you can find a source text that speaks to you, for whatever reason, then you will find valuable use in erasing that text.

Erasure of Ernest Hemingway “In Search of Lost TIme”

Why Are Your Poems So Big?

I printed my first “large-scale” erasure poem in May of 2019. Below is a photo I snapped of myself, and I think it shows the sheer panic I felt over the idea. It took me another year to paint the poem and yet another year to submit this poem, among others, to an art venue for an exhibition.

I’m not sure where the idea of large-scale poems came from, but I couldn't let it go once it was in my head. Part of it is that erasure poems are like miniature works of art. There’s a limitation in the size of the paper — either a newspaper or a book page.

But what if size wasn’t an issue? I realized that I could reproduce a book page at a large scale and make a piece of art.

The poem is big because the work is big. Scale forces us to see detail.

One of my first large-scale erasures was accepted to the Lawndale Art Center Big Show, a local artist exhibition space.

I then started planning to submit to other artist opportunities to see if I could get anyone interested in my poetry.

And someone said yes! That is how I ended up with a full solo exhibition in April of this year in celebration of National Poetry Month at Sabine Street Studios in Houston, TX.

I was so excited and also a bit terrified. But I knew that giant poems would be a fascinating way to celebrate erasure poetry. There was one problem. The show was three weeks away, and the space for my art was ginormous. I needed to make at least 20 pieces in three weeks.

Trust the Process

We often consider writing an act of repetition. Many schools of writing teach revision, revision, and more revision. Less emphasis gets placed on the creative impetus behind the words. I feel this is why many writers struggle to create — what comes out isn’t perfect, and the prospect of revision is daunting.

The art of the erasure poem means there is no revision (or very little). You can plan which words you will erase, but if you make a mistake in the erasing, you have to either embrace that mistake or scrap the work entirely.

You can’t erase the erasure.

A great example is my poem from the show “Taxidermy.” I knew I wanted to cover the poem entirely in bird eggs. I was going for an old-fashioned, sepia vibe. The text is from an old book on women artists. It featured all the standard “women’s” arts at the time (in the Victorian era) of china painting and landscape painting.

But it also had an entire chapter on how women could skin any number of animals for taxidermy purposes.

I didn't like my dainty eggs because they looked too Eastery, so I covered them in blood splotches. Coincidentally, I also managed to cut myself on the plexiglass when framing this piece, so it also contains some of my blood.

Making 22 giant erasure poems in fewer than three weeks taught me much about myself as a creative person. Sure, I was exhausted at the end. I was nervous about what I had created. But I was also deliriously happy.

The best part of writing (for me, at least) is that first idea, which often comes out of nowhere. That first spark of imagination comes from the interior self — the creative part of you. If you lose that part, the writing loses its life.

When creating giant erasure poems, I frame them so the page isn’t flat. I give space between the frame, the glass, and the art. That’s because I want the page to have life for the viewer, to look like a real book page, only ginormous.

This process of hyper-fast creation is akin to April’s NaPoWriMo or National Poetry Month, where writers create 30 poems in 30 days. Putting a time limit on the work forced me to embrace my mistakes and find ways to work around them. The result may not be perfect, but it distills my process.

That’s what “trust the process,” one of my favorite creative sayings, means to me.

Some pieces of art take hours. Some take years. All are part of the process of creative awakening.

“Taxidermy” a large-scale erasure poem

Holly Lyn Walrath is a poet living in Houston, Texas. She is the author of several books of poetry, including Glimmerglass Girl (2018), The Smallest of Bones (2021), and Numinous Stones (2023). She holds a B.A. in English from The University of Texas and a Master’s in Creative Writing from the University of Denver.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK