Kaspersky in the Middle – what could possibly go wrong?

source link: https://palant.info/2019/08/19/kaspersky-in-the-middle--what-could-possibly-go-wrong/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Kaspersky in the Middle – what could possibly go wrong?

Roughly a decade ago I read an article that asked antivirus vendors to stop intercepting encrypted HTTPS connections, this practice actively hurting security and privacy. As you can certainly imagine, antivirus vendors agreed with the sensible argument and today no reasonable antivirus product would even consider intercepting HTTPS traffic. Just kidding… Of course they kept going, and so two years ago a study was published detailing the security issues introduced by interception of HTTPS connections. Google and Mozilla once again urged antivirus vendors to stop. Surely this time it worked?

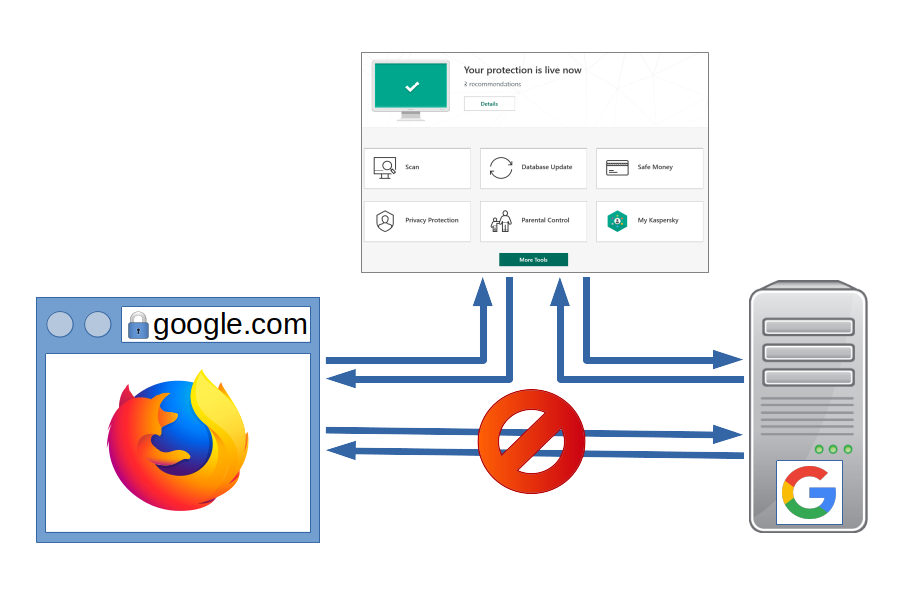

Of course not. So when I decided to look into Kaspersky Internet Security in December last year, I found it breaking up HTTPS connections so that it would get between the server and your browser in order to “protect” you. Expecting some deeply technical details about HTTPS protocol misimplementations now? Don’t worry, I don’t know enough myself to inspect Kaspersky software on this level. The vulnerabilities I found were far more mundane.

I reported eight vulnerabilities to Kaspersky Lab between 2018-12-13 and 2018-12-21. This article will only describe three vulnerabilities which have been fixed in April this year. This includes two vulnerabilities that weren’t deemed a security risk by Kaspersky, it’s up to you to decide whether you agree with this assessment. The remaining five vulnerabilities have only been fixed in July, and I agreed to wait until November with the disclosure to give users enough time to upgrade.

Edit (2019-08-22): In order to disable this functionality you have to go into Settings, select “Additional” on the left side, then click “Network.” There you will see a section called “Encryption connection scanning” where you need to choose “Do not scan encrypted connections.”

The underappreciated certificate warning pages

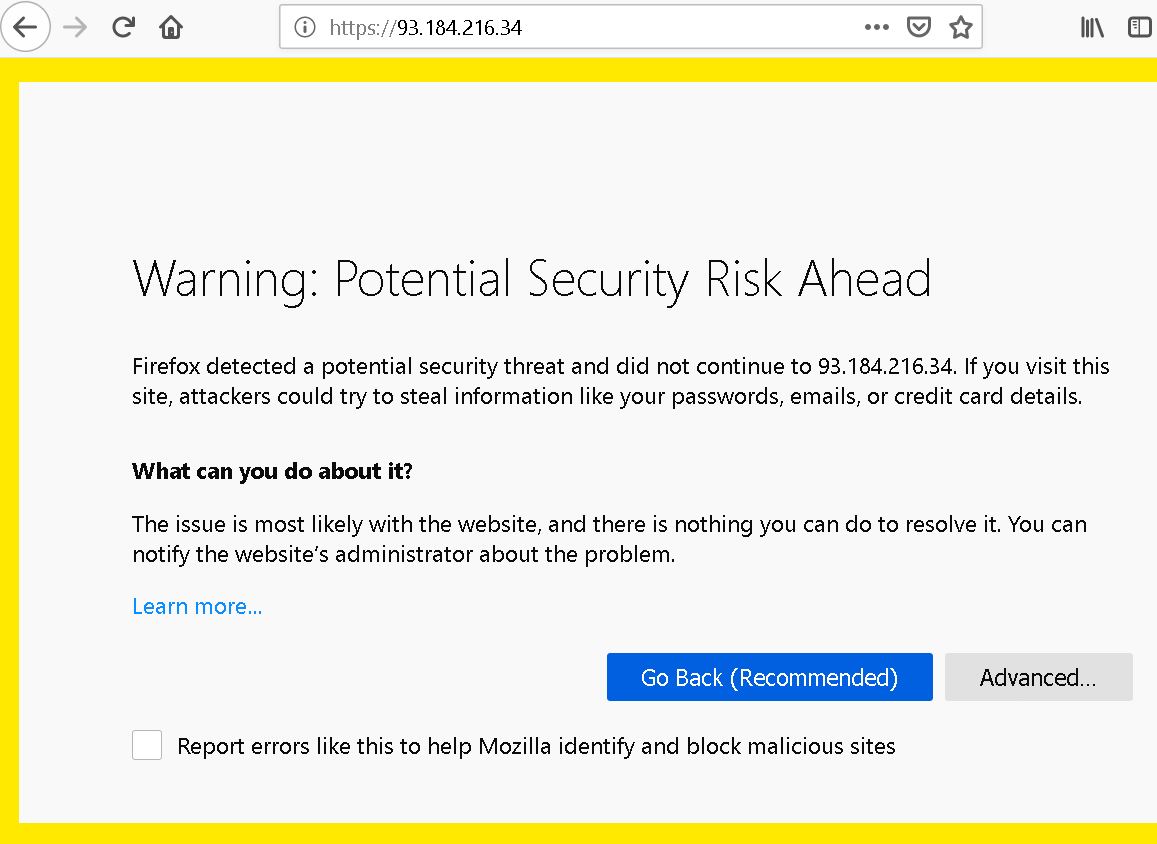

There is an important edge case with HTTPS connections: what if a connection is established but the other side uses an invalid certificate? Current browsers will generally show you a certificate warning page in this scenario. In Firefox it looks like this:

This page has seen a surprising amount of changes over the years. The browser vendors recognized that asking users to make a decision isn’t a good idea here. Most of the time, getting out is the best course of action, and ignoring the warning only a viable option for very technical users. So the text here is very clear, low on technical details, and the recommended solution is highlighted. The option to ignore the warning is well-hidden on the other hand, to prevent people from using it without understanding the implications. While the page looks different in other browsers, the main design considerations are the same.

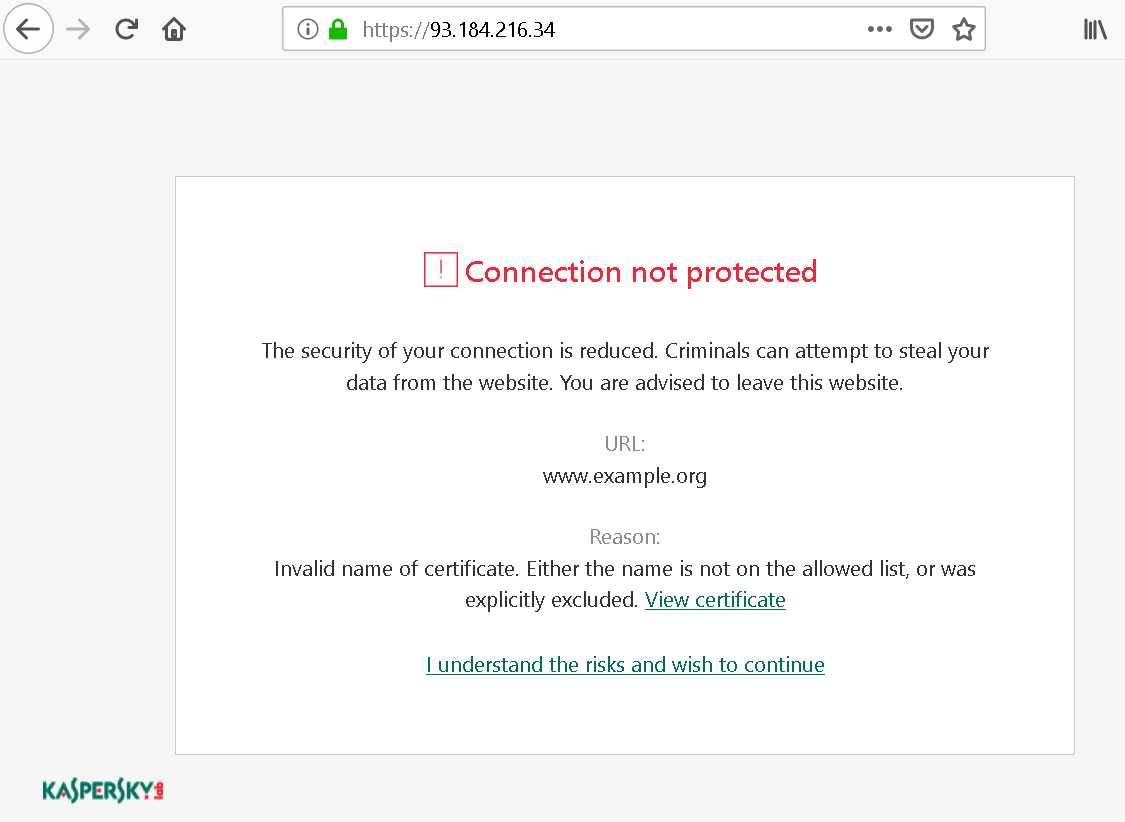

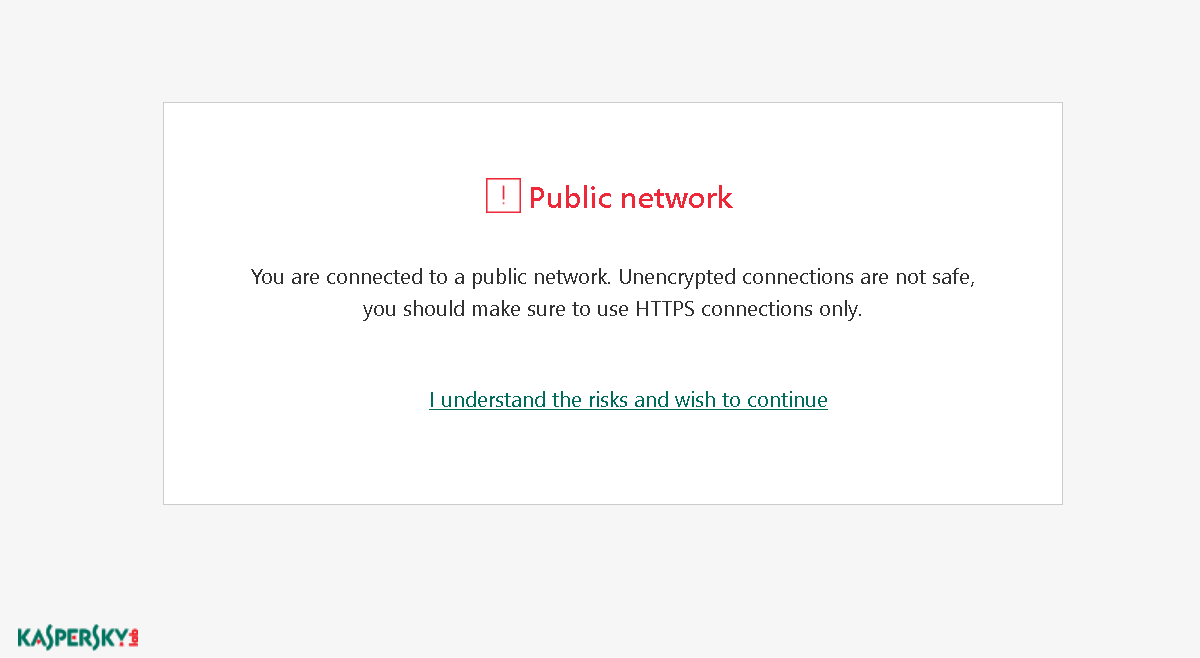

But with Kaspersky Internet Security in the middle, the browser is no longer talking to the server, Kaspersky is. The way HTTPS is designed, it means that Kaspersky is responsible for validating the server’s certificate and producing a certificate warning page. And that’s what the certificate warning page looks like then:

There is a considerable amount of technical details here, supposedly to allow users to make an informed decision, but usually confusing them instead. Oh, and why does it list the URL as “www.example.org”? That’s not what I typed into the address bar, it’s actually what this site claims to be (the name has been extracted from the site’s invalid certificate). That’s a tiny security issue here, wasn’t worth reporting however as this only affects sites accessed by IP address which should never be the case with HTTPS.

The bigger issue: what is the user supposed to do here? There is “leave this website” in the text, but experience shows that people usually won’t read when hitting a roadblock like this. And the highlighted action here is “I understand the risks and wish to continue” which is what most users can be expected to hit.

Using clickjacking to override certificate warnings

Let’s say that we hijacked some user’s web traffic, e.g. by tricking them into connecting to our malicious WiFi hotspot. Now we want to do something evil with that, such as collecting their Google searches or hijacking their Google account. Unfortunately, HTTPS won’t let us do it. If we place ourselves between the user and the Google server, we have to use our own certificate for the connection to the user. With our certificate being invalid, this will trigger a certificate warning however.

So the goal is to make the user click “I understand the risks and wish to continue” on the certificate warning page. We could just ask nicely, and given how this page is built we’ll probably succeed in a fair share of cases. Or we could use a trick called clickjacking – let the user click it without realizing what they are clicking.

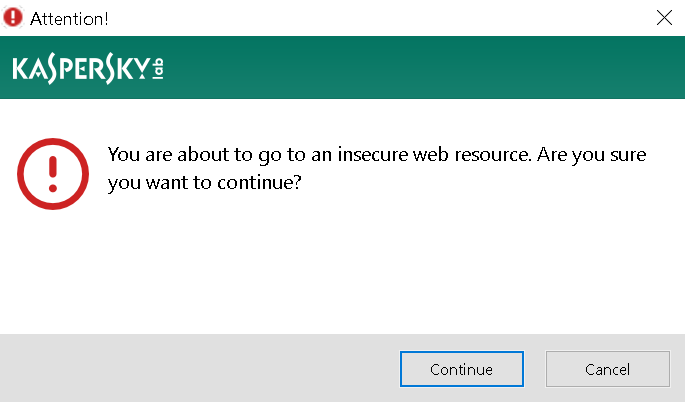

There is only one complication. When the link is clicked there will be an additional confirmation pop-up:

But don’t despair just yet! That warning is merely generic text, it would apply to any remotely insecure action. We would only need to convince the user that the warning is expected and they will happily click “Continue.” For example, we could give them the following page when they first connect to the network, similar to those captive portals:

Looks like a legitimate Kaspersky warning page but isn’t, the text here was written by me. The only “real” thing here is the “I understand the risks and wish to continue” link which actually belongs to an embedded frame. That frame contains Kaspersky’s certificate warning for www.google.com and has been positioned in such a way that only the link is visible. When the user clicks it, they will get the generic warning from above and without doubt confirm ignoring the invalid certificate. We won, now we can do our evil thing without triggering any warnings!

How browser vendors deal with this kind of attack? They require at least two clicks to happen on different spots of the certificate warning page in order to add an exception for an invalid certificate, this makes clickjacking attacks impracticable. Kaspersky on the other hand felt very confident about their warning prompt, so they opted for adding more information to it. This message will now show you the name of the site you are adding the exception for. Let’s just hope that accessing a site by IP address is the only scenario where attackers can manipulate that name…

Something you probably don’t know about HSTS

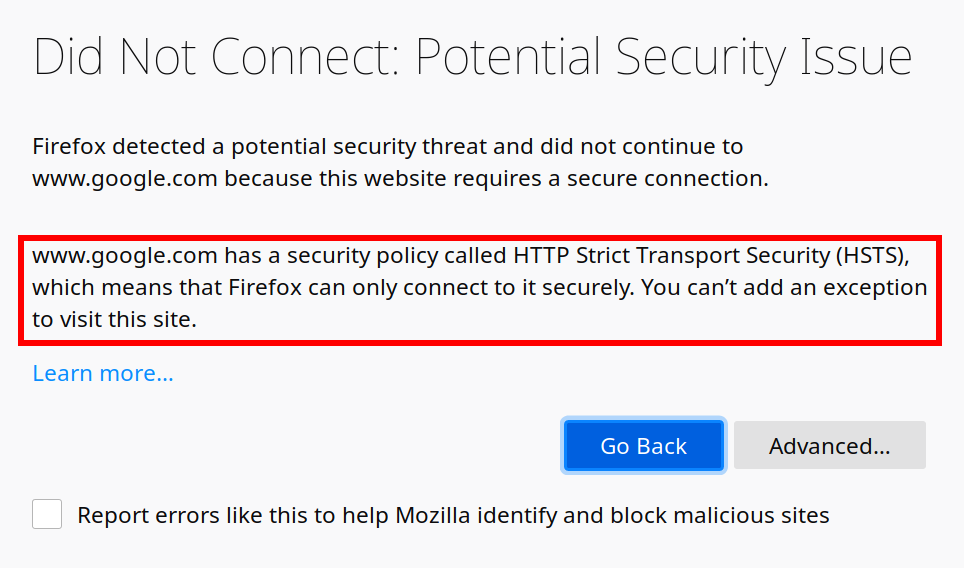

There is a slightly less obvious detail to the attack described above: it shouldn’t have worked at all. See, if you reroute www.google.com traffic to a malicious server and navigate to the site then, neither Firefox nor Chrome will give you the option to override the certificate warning. Getting out will be the only option available, meaning no way whatsoever to exploit the certificate warning page. What is this magic? Did browsers implement some special behavior only for Google?

They didn’t. What you see here is a side-effect of the HTTP Strict-Transport-Security (HSTS) mechanism, which Google and many other websites happen to use. When you visit Google it will send the HTTP header Strict-Transport-Security: max-age=31536000 with the response. This tells the browser: “This is an HTTPS-only website, don’t ever try to create an unencrypted connection to it. Keep that in mind for the next year.”

So when the browser later encounters a certificate error on a site using HSTS, it knows: the website owner promised to keep HTTPS functional. There is no way that an invalid certificate is ok here, so allowing users to override the certificate would be wrong.

Unless you have Kaspersky in the middle of course, because Kaspersky completely ignores HSTS and still allows users to override the certificate. When I reported this issue, the vendor response was that this isn’t a security risk because the warning displayed is sufficient. Somehow they decided to add support for HSTS nevertheless, so that current versions will no longer allow overriding certificates here.

It’s no doubt that there are more scenarios where Kaspersky software weakens the security precautions made by browsers. For example, if a certificate is revoked (usually because it has been compromised), browsers will normally recognize that thanks to OCSP stapling and prevent the connection. But I noticed recently that Kaspersky Internet Security doesn’t support OCSP stapling, so if this application is active it will happily allow you to connect to a likely malicious server.

Using injected content for Universal XSS

Kaspersky Internet Security isn’t merely listening in on connections to HTTPS sites, it is also actively modifying those. In some cases it will generate a response of its own, such as the certificate warning page we saw above. In others it will modify the response sent by the server.

For example, if you didn’t install the Kaspersky browser extension, it will fall back to injecting a script into server responses which is then responsible for “protecting” you. This protection does things like showing a green checkmark next to Google search results that are considered safe. As Heise Online wrote merely a few days ago, this also used to leak a unique user ID which allowed tracking users regardless of any protective measures on their side. Oops…

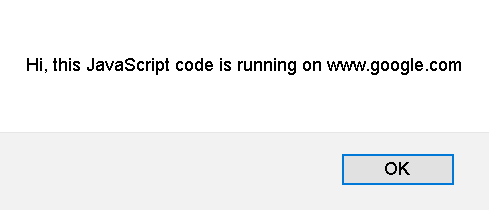

There is a bit more to this feature called URL Advisor. When you put the mouse cursor above the checkmark icon a message appears stating that you have a safe site there. That message is a frame displaying url_advisor_balloon.html. Where does this file load from? If you have the Kaspersky browser extension, it will be part of that browser extension. If you don’t, it will load from ff.kis.v2.scr.kaspersky-labs.com in Firefox and gc.kis.v2.scr.kaspersky-labs.com in Chrome – Kaspersky software will intercept requests to these servers and answer them locally. I noticed however that things were different in Microsoft Edge, here this file would load directly from www.google.com (or any other website if you changed the host name).

Certainly, when injecting their own web page into every domain on the web Kaspersky developers thought about making it very secure? Let’s have a look at the code running there:

var policeLink = document.createElement("a");

policeLink.href = IsDefined(UrlAdvisorLinkPoliceDecision) ? UrlAdvisorLinkPoliceDecision : locales["UrlAdvisorLinkPoliceDecision"];

policeLink.target = "_blank";

div.appendChild(policeLink);This creates a link inside the frame dynamically. Where the link target comes from? It’s part of the data received from the parent document, no validation performed. In particular, javascript: links will be happily accepted. So a malicious website needs to figure out the location of url_advisor_balloon.html and embed it in a frame using the host name of the website they want to attack. Then they send a message to it:

frame.contentWindow.postMessage(JSON.stringify({

command: "init",

data: {

verdict: {

url: "",

categories: [

21

]

},

locales: {

UrlAdvisorLinkPoliceDecision: "javascript:alert('Hi, this JavaScript code is running on ' + document.domain)",

CAT_21: "click here"

}

}

}), "*");What you get is a link labeled “click here” which will run arbitrary JavaScript code in the context of the attacked domain when clicked. And once again, the attackers could ask the user nicely to click it. Or they could use clickjacking, so whenever the user clicks anywhere on their site, the click goes to this link inside an invisible frame.

And here you have it: a malicious website taking over your Google or social media accounts, all because Kaspersky considered it a good idea to have their content injected into secure traffic of other people’s domains. But at least this particular issue was limited to Microsoft Edge.

Timeline

- 2018-12-13: Sent report via Kaspersky bug bounty program: Lack of HSTS support facilitating MiTM attacks.

- 2018-12-17: Sent reports via Kaspersky bug bounty program: Certificate warning pages susceptible to clickjacking and Universal XSS in Microsoft Edge.

- 2018-12-20: Response from Kaspersky: HSTS and clickjacking reports are not considered security issues.

- 2018-12-20: Requested disclosure of the HSTS and clickjacking reports.

- 2018-12-24: Disclosure denied due to similarity with one of my other reports.

- 2019-04-29: Kaspersky notifies me about the three issues here being fixed (KIS 2019 Patch E, actually released three weeks earlier).

- 2019-04-29: Requested disclosure of these three issues, no response.

- 2019-07-29: With five remaining issues reported by me fixed (KIS 2019 Patch F and KIS 2020), requested disclosure on all reports.

- 2019-08-04: Disclosure denied on HSTS report because “You’ve requested too many tickets for disclosure at the same time.”

- 2019-08-05: Disclosure denied on five not yet disclosed reports, asking for time until November for users to update.

- 2019-08-06: Notified Kaspersky about my intention to publish an article about the three issues here on 2019-08-19, no response.

- 2019-08-12: Reminded Kaspersky that I will publish an article on these three issues on 2019-08-19.

- 2019-08-12: Kaspersky requesting an extension of the timeline until 2019-08-22, citing that they need more time to prepare.

- 2019-08-16: Security advisory published by Kaspersky without notifying me.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK