Hadamard product (matrices)

source link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hadamard_product_(matrices)

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Hadamard product (matrices)

Jump to navigation Jump to search

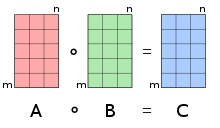

In mathematics, the Hadamard product (also known as the element-wise product, entrywise product[1]: ch. 5 or Schur product[2]) is a binary operation that takes two matrices of the same dimensions and produces another matrix of the same dimension as the operands, where each element i, j is the product of elements i, j of the original two matrices. It is to be distinguished from the more common matrix product. It is attributed to, and named after, either French mathematician Jacques Hadamard or German Russian mathematician Issai Schur.

The Hadamard product is associative and distributive. Unlike the matrix product, it is also commutative.[3]

Definition[edit]

For two matrices A and B of the same dimension m × n, the Hadamard product A∘B{\displaystyle A\circ B}

(A∘B)ij=(A⊙B)ij=(A)ij(B)ij.{\displaystyle (A\circ B)_{ij}=(A\odot B)_{ij}=(A)_{ij}(B)_{ij}.}

For matrices of different dimensions (m × n and p × q, where m ≠ p or n ≠ q), the Hadamard product is undefined.

Example[edit]

For example, the Hadamard product for a 3 × 4 matrix A with a 3 × 4 matrix B is

[a11a12a13a14a21a22a23a24a31a32a33a34]∘[b11b12b13b14b21b22b23b24b31b32b33b34]=[a11b11a12b12a13b13a14b14a21b21a22b22a23b23a24b24a31b31a32b32a33b33a34b34].{\displaystyle {\begin{bmatrix}a_{11}&a_{12}&a_{13}&a_{14}\\a_{21}&a_{22}&a_{23}&a_{24}\\a_{31}&a_{32}&a_{33}&a_{34}\end{bmatrix}}\circ {\begin{bmatrix}b_{11}&b_{12}&b_{13}&b_{14}\\b_{21}&b_{22}&b_{23}&b_{24}\\b_{31}&b_{32}&b_{33}&b_{34}\end{bmatrix}}={\begin{bmatrix}a_{11}\,b_{11}&a_{12}\,b_{12}&a_{13}\,b_{13}&a_{14}\,b_{14}\\a_{21}\,b_{21}&a_{22}\,b_{22}&a_{23}\,b_{23}&a_{24}\,b_{24}\\a_{31}\,b_{31}&a_{32}\,b_{32}&a_{33}\,b_{33}&a_{34}\,b_{34}\end{bmatrix}}.}

Properties[edit]

- The Hadamard product is commutative (when working with a commutative ring), associative and distributive over addition. That is, if A, B, and C are matrices of the same size, and k is a scalar: A∘B=B∘A,A∘(B∘C)=(A∘B)∘C,A∘(B+C)=A∘B+A∘C,(kA)∘B=A∘(kB)=k(A∘B),A∘0=0∘A=0.{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}A\circ B&=B\circ A,\\A\circ (B\circ C)&=(A\circ B)\circ C,\\A\circ (B+C)&=A\circ B+A\circ C,\\\left(kA\right)\circ B&=A\circ \left(kB\right)=k\left(A\circ B\right),\\A\circ 0&=0\circ A=0.\end{aligned}}}

- The identity matrix under Hadamard multiplication of two m × n matrices is an m × n matrix where all elements are equal to 1. This is different from the identity matrix under regular matrix multiplication, where only the elements of the main diagonal are equal to 1. Furthermore, a matrix has an inverse under Hadamard multiplication if and only if none of the elements are equal to zero.[7]

- For vectors x and y, and corresponding diagonal matrices Dx and Dy with these vectors as their main diagonals, the following identity holds:[1]: 479 where x* denotes the conjugate transpose of x. In particular, using vectors of ones, this shows that the sum of all elements in the Hadamard product is the trace of ABT where superscript T denotes the matrix transpose. A related result for square A and B, is that the row-sums of their Hadamard product are the diagonal elements of ABT:[8]x∗(A∘B)y=tr(Dx∗ADyBT),{\displaystyle \mathbf {x} ^{*}(A\circ B)\mathbf {y} =\operatorname {tr} \left({D}_{\mathbf {x} }^{*}A{D}_{\mathbf {y} }{B}^{\mathsf {T}}\right),}Similarly,∑i(A∘B)ij=(BTA)jj=(ABT)ii.{\displaystyle \sum _{i}(A\circ B)_{ij}=\left(B^{\mathsf {T}}A\right)_{jj}=\left(AB^{\mathsf {T}}\right)_{ii}.}Furthermore a Hadamard matrix-vector product can be expressed as:(yx∗)∘A=DyADx∗{\displaystyle \left(\mathbf {y} \mathbf {x} ^{*}\right)\circ A={D}_{\mathbf {y} }A{D}_{\mathbf {x} }^{*}}where diag(M){\displaystyle \operatorname {diag} (M)}(A∘B)y=diag(ADyBT){\displaystyle (A\circ B)\mathbf {y} =\operatorname {diag} \left(AD_{\mathbf {y} }B^{\mathsf {T}}\right)}

is the vector formed from the diagonals of matrix M.

- The Hadamard product is a principal submatrix of the Kronecker product.[9]

- The Hadamard product satisfies the rank inequality rank(A∘B)≤rank(A)rank(B){\displaystyle \operatorname {rank} (A\circ B)\leq \operatorname {rank} (A)\operatorname {rank} (B)}

- If A and B are positive-definite matrices, then the following inequality involving the Hadamard product holds:[10]where λi(A) is the ith largest eigenvalue of A.∏i=knλi(A∘B)≥∏i=knλi(AB),k=1,…,n,{\displaystyle \prod _{i=k}^{n}\lambda _{i}(A\circ B)\geq \prod _{i=k}^{n}\lambda _{i}(AB),\quad k=1,\ldots ,n,}

- If D and E are diagonal matrices, then[11]D(A∘B)E=(DAE)∘B=(DA)∘(BE)=(AE)∘(DB)=A∘(DBE).{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}D(A\circ B)E&=(DAE)\circ B=(DA)\circ (BE)\\&=(AE)\circ (DB)=A\circ (DBE).\end{aligned}}}

- The Hadamard product of two vectors a{\displaystyle \mathbf {a} }

and b{\displaystyle \mathbf {b} }

is the same as matrix multiplication of one vector by the corresponding diagonal matrix of the other vector:

a∘b=Dab=Dba{\displaystyle \mathbf {a} \circ \mathbf {b} =D_{\mathbf {a} }\mathbf {b} =D_{\mathbf {b} }\mathbf {a} } - The vector to diagonal matrix may be expressed using the Hadamard product as: where 1{\displaystyle \mathbf {1} }diag(a)=(a1T)∘I{\displaystyle \operatorname {diag} (\mathbf {a} )=(\mathbf {a} \mathbf {1} ^{T})\circ I}

is a constant vector with elements 1{\displaystyle 1}

and I{\displaystyle I}

is the identity matrix.

The mixed-product property[edit]

where ⊗{\displaystyle \otimes }

where ∙{\displaystyle \bullet }

where ∗{\displaystyle \ast }

Schur product theorem[edit]

The Hadamard product of two positive-semidefinite matrices is positive-semidefinite.[3][8] This is known as the Schur product theorem,[7] after Russian mathematician Issai Schur. For two positive-semidefinite matrices A and B, it is also known that the determinant of their Hadamard product is greater than or equal to the product of their respective determinants:[8]

In programming languages[edit]

Hadamard multiplication is built into certain programming languages under various names. In MATLAB, GNU Octave, GAUSS and HP Prime, it is known as array multiplication, or in Julia broadcast multiplication, with the symbol .*.[13] In Fortran, R,[14]APL, J and Wolfram Language (Mathematica), it is done through simple multiplication operator *, whereas the matrix product is done through the function matmul, %*%, +.×, +/ .* and the . operators, respectively.

In Python with the NumPy numerical library, multiplication of array objects as a*b produces the Hadamard product, and multiplication as a@b produces the matrix product. With the SymPy symbolic library, multiplication of array objects as both a*b and a@b will produce the matrix product, the Hadamard product can be obtained with a.multiply_elementwise(b).[15]

In C++, the Eigen library provides a cwiseProduct member function for the Matrix class (a.cwiseProduct(b)), while the Armadillo library uses the operator % to make compact expressions (a % b; a * b is a matrix product). R package matrixcalc introduces function hadamard.prod() for Hadamard Product of numeric matrices or vectors.

Applications[edit]

The Hadamard product appears in lossy compression algorithms such as JPEG. The decoding step involves an entry-for-entry product, in other words the Hadamard product.[citation needed]

In image processing, the Hadamard operator can be used for enhancing, suppressing or masking image regions. One matrix represents the original image, the other acts as weight or masking matrix.

It is used in the machine learning literature, for example to describe the architecture of recurrent neural networks as GRUs or LSTMs.[16]

It is also used to study statistical properties of random vectors and matrices. [17][18]

Analogous operations[edit]

Other Hadamard operations are also seen in the mathematical literature,[19] namely the Hadamard root and Hadamard power (which are in effect the same thing because of fractional indices), defined for a matrix such that:

and for

The Hadamard inverse reads:[19]

A Hadamard division is defined as:[20][21]

The penetrating face product[edit]

According to the definition of V. Slyusar the penetrating face product of the p×g matrix A{\displaystyle {A}}

![{\displaystyle {B}=[B_{n}]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/45506cf4a375f39c45f90de563b9205a11583669)

![{\displaystyle {A}[\circ ]{B}=\left[{\begin{array}{c | c | c | c }{A}\circ {B}_{1}&{A}\circ {B}_{2}&\cdots &{A}\circ {B}_{n}\end{array}}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/66b68d039b99d242c23c28f1e3903da7089202d9)

Example[edit]

![{\displaystyle {A}={\begin{bmatrix}1&2&3\\4&5&6\\7&8&9\end{bmatrix}},\quad {B}=\left[{\begin{array}{c | c | c }{B}_{1}&{B}_{2}&{B}_{3}\end{array}}\right]=\left[{\begin{array}{c c c | c c c | c c c }1&4&7&2&8&14&3&12&21\\8&20&5&10&25&40&12&30&6\\2&8&3&2&4&2&7&3&9\end{array}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/22cfbfc085d4db857aa37b904582490684c468ea)

![{\displaystyle {A}[\circ ]{B}=\left[{\begin{array}{c c c | c c c | c c c }1&8&21&2&16&42&3&24&63\\32&100&30&40&125&240&48&150&36\\14&64&27&14&32&18&49&24&81\end{array}}\right].}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/583d6366905bb0028a53c16817a4a22f861a61b1)

Main properties[edit]

A[∘]B=B[∘]A;{\displaystyle {A}[\circ ]{B}={B}[\circ ]{A};}![{\displaystyle {A}[\circ ]{B}={B}[\circ ]{A};}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4b37f0dbd03375c1a75119b2819674c1be473510)

where ∙{\displaystyle \bullet }

c∙M=c[∘]M,{\displaystyle \mathbf {c} \bullet {M}=\mathbf {c} [\circ ]{M},}![{\displaystyle \mathbf {c} \bullet {M}=\mathbf {c} [\circ ]{M},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e2d3e0488429a71b50662fe2babe262dadf73c32)

Applications[edit]

The penetrating face product is used in the tensor-matrix theory of digital antenna arrays.[22] This operation can also be used in artificial neural network models, specifically convolutional layers.[23]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Horn, Roger A.; Johnson, Charles R. (2012). Matrix analysis. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Davis, Chandler (1962). "The norm of the Schur product operation". Numerische Mathematik. 4 (1): 343–44. doi:10.1007/bf01386329. S2CID 121027182.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Million, Elizabeth (April 12, 2007). "The Hadamard Product" (PDF). buzzard.ups.edu. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ "Hadamard product - Machine Learning Glossary". machinelearning.wtf.

- ^ "linear algebra - What does a dot in a circle mean?". Mathematics Stack Exchange.

- ^ "Element-wise (or pointwise) operations notation?". Mathematics Stack Exchange.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Million, Elizabeth. "The Hadamard Product" (PDF). Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Styan, George P. H. (1973), "Hadamard Products and Multivariate Statistical Analysis", Linear Algebra and Its Applications, 6: 217–240, doi:10.1016/0024-3795(73)90023-2, hdl:10338.dmlcz/102190

- ^ Liu, S.; Trenkler, G. (2008). "Hadamard, Khatri-Rao, Kronecker and other matrix products". International Journal of Information and Systems Sciences. 4 (1): 160–177.

- ^ Hiai, Fumio; Lin, Minghua (February 2017). "On an eigenvalue inequality involving the Hadamard product". Linear Algebra and Its Applications. 515: 313–320. doi:10.1016/j.laa.2016.11.017.

- ^ "Project" (PDF). buzzard.ups.edu. 2007. Retrieved 2019-12-18.

- ^ Slyusar, V. I. (1998). "End products in matrices in radar applications" (PDF). Radioelectronics and Communications Systems. 41 (3): 50–53.

- ^ "Arithmetic Operators + - * / \ ^ ' -". MATLAB documentation. MathWorks. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ^ "Matrix multiplication". An Introduction to R. The R Project for Statistical Computing. 16 May 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- ^ "Common Matrices — SymPy 1.9 documentation".

- ^ Sak, Haşim; Senior, Andrew; Beaufays, Françoise (2014-02-05). "Long Short-Term Memory Based Recurrent Neural Network Architectures for Large Vocabulary Speech Recognition". arXiv:1402.1128 [cs.NE].

- ^ Neudecker, H.; Liu, S.; Polasek, W. (1995). "The Hadamard product and some of its applications in statistics". Statistics. 26 (4): 365–373. doi:10.1080/02331889508802503.

- ^ Neudecker, H.; Liu, S. (2001). "Some statistical properties of Hadamard products of random matrices". Statistical Papers. 42 (4): 475–487. doi:10.1007/s003620100074. S2CID 121385730.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Reams, Robert (1999). "Hadamard inverses, square roots and products of almost semidefinite matrices". Linear Algebra and Its Applications. 288: 35–43. doi:10.1016/S0024-3795(98)10162-3.

- ^ Wetzstein, Gordon; Lanman, Douglas; Hirsch, Matthew; Raskar, Ramesh. "Supplementary Material: Tensor Displays: Compressive Light Field Synthesis using Multilayer Displays with Directional Backlighting" (PDF). MIT Media Lab.

- ^ Cyganek, Boguslaw (2013). Object Detection and Recognition in Digital Images: Theory and Practice. John Wiley & Sons. p. 109. ISBN 9781118618363.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Slyusar, V. I. (March 13, 1998). "A Family of Face Products of Matrices and its properties" (PDF). Cybernetics and Systems Analysis C/C of Kibernetika I Sistemnyi Analiz. 1999. 35 (3): 379–384. doi:10.1007/BF02733426. S2CID 119661450.

- ^ Ha D., Dai A.M., Le Q.V. (2017). "HyperNetworks". The International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR) 2017. – Toulon, 2017.: Page 6. arXiv:1609.09106.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK

![{\displaystyle {M}\bullet {M}={M}[\circ ]\left({M}\otimes \mathbf {1} ^{\textsf {T}}\right),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/77ac436dde23cffd0b06482d2aede5b33f46f46e)