In Defense of Missile Defense

source link: https://www.navalgazing.net/In-Defense-of-Missile-Defense

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

In Defense of Missile Defense

Probably the most curious gap in the current debate around defense issues is the subject of missile defense. Despite the possibility to meaningfully reduce the danger from nuclear war, it is largely ignored, and when it does come up it is widely misunderstood. I’ve referenced this before, but figured it was time to lay out the argument in more detail.

The basic case for missile defense is quite simple: nuclear weapons aren’t something you want detonating in your country, and shooting them down seems like a good idea. But as appealing as this is, it is usually countered by a pair of counterarguments, that it’s far too hard to shoot down all incoming missiles, and that it would be destabilizing if it was possible. But this relies on the basic premise that any missile defense system which can’t shoot down all missiles is useless, and there’s no reason that would be true unless someone was smuggling it in to defeat missile defense for other reasons. (We’ll come back to that in a bit.) A system which stops 50% of incoming missiles means that only half as many people will die in a nuclear war,1 obviously a desirable result.

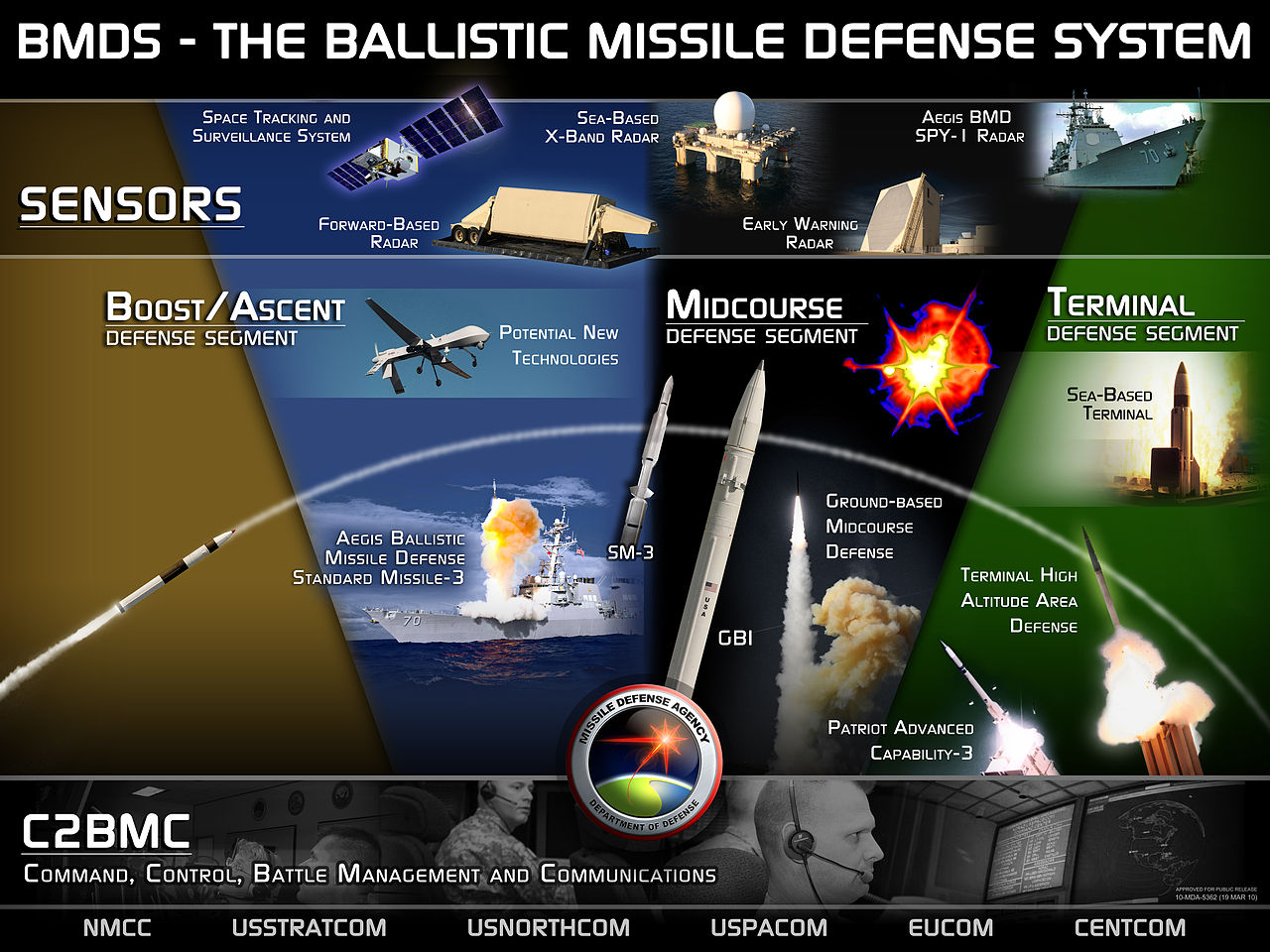

The difficulty of shooting down an incoming missile is broadly overstated. We routinely play sports (baseball, cricket, skeet shooting) where an unaided human has to intercept a ballistic target, and while those humans don’t have a perfect success rate, they also don’t have radar, computers, or multiple chances. More practically, the US has invested a fair bit in this field over the last 30 years, and those efforts have paid off, leaving us with an array of anti-missile systems. The big three are GMD, which is designed to protect the continental US from ICBMs, Aegis BMD, a ship-based system intended for use against theater missiles that has gained anti-ICBM capability in recent years, and THAAD, a mobile ground-based system intended to counter shorter-range missiles. All of these have performed well in testing, getting over 50% of hits, sometimes well over, with failures having far more to do with hardware issues than with the inherent difficulty of hitting an incoming warhead. Obviously, these are one-off tests in ideal conditions, and there’s at least a chance that the testing setup obscures some significant systemic issue that will render the whole thing useless when missiles actually start flying. I can only point out that the defense industry has generally proved to be pretty good at building robust systems given enough time and money, although it usually takes more of both than anyone would like.

The other thing usually brought up as a counter to missile defense is the potential use of decoys, flooding the system with targets at low cost. In practice, this seems to be far more difficult than it first appears, although details are elusive and the best source of information is what missile designers actually did to try to penetrate missile defenses. The basic problem with decoys is that they only work so long as they are indistinguishable from the warhead, and thanks to modern computers and sensors, this is much harder than it used to be. Even back in the 60s and 70s, there were serious concerns about the effectiveness of decoys, prompting the designers of Poseidon to decide that the best decoy would be the same size and weight as an actual warhead, in which case they might as well put the nuclear payload in as well. The British Chevaline decoy system was a major technical challenge in the late 70s, and it seems doubtful that the techniques used then would still be effective. The last half-century has seen very little in the way of better decoy technology, and massive improvements in discrimination.

But the uncertainty of any missile defense system brings us naturally to the second prong of the argument of missile defense, that it is inherently destabilizing. The theory goes that a 100% impenetrable missile defense would undermine deterrence, allowing the nation that owned it to strike with impunity, and thus prompting the opponent to launch before the system is ready. While this is true as far as it goes, we should instead examine what happens in the real world, where any missile defense system is necessarily going to be imperfect. In that case, it’s far from obvious that missile defense is destabilizing. Even if we assume that the US builds a system capable of shooting down 99% of all incoming missiles, that’s still going to mean that China can land 3 or so warheads on US territory, and Russia probably 10-15. In practice, no leader this side of Stalin is likely to court those kind of losses unless they really need to, no matter how much they stand to gain from it. People are remarkably scope-insensitive when it comes to nuclear weapons, with North Korea deterring the US with 6 warheads (one for every 7 American interceptors) nearly as effectively as Russia does with 1550. A strong ABM shield would also provide a great deal more security against accidental launches. A few ICBMs inbound for whatever reason are less concerning when most or all of them can be dealt with before impact, giving decision-makers more time to respond and reducing the risk of escalation.

But if the case for ABM is fairly straightforward, why is the case against it so common in discussions? This goes back to that root of all kinds of evil, Robert McNamara and the Kennedy/Johnson Administration. When they entered office, they inherited the Nike-Zeus ABM system, which was almost ready for deployment. McNamara didn’t think it was a particularly cost-effective system, but chose to justify his cancellation on the basis of general ineffectiveness instead of poor value for money. This critique was later picked up in the 80s by critics of Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, whose opposition often seemed to flow more from political opposition to Reagan than from a technical evaluation of the merits of the system.2

But the obvious conclusion of all of this is that the US is in a position where we can easily build a missile defense shield, the biggest problem being the political will to buy the weapons in sufficient quantities. Procurement has lagged for years, with only 44 interceptors for the GMD system currently installed to protect the US mainland and no more planned. The situation is slightly better for theater missile defense, with the Navy having about 265 SM-3s and a few hundred more THAADs for the Army. The obvious solution, underscored by recent events in Ukraine, is to expand our missile defense net. The lowest-risk way to do is to buy more SM-3s for the Navy, as SM-3 has proven the most effective of the systems and the line is still hot. The SM-3 Block IIA’s capability against ICBMs should also make us take a close look at installing Aegis Ashore near our major cities and military bases. In addition to providing proven ABM protection with minimal development costs, this would also give the areas around the installations a world-class air defense system, capable of dealing with atmospheric threats, which American cities have had no reliable protection against since the Nike system was shut down in the 1970s. As the GMD interceptors were rather rushed into service, it probably makes sense to wait on expanding that system until the new interceptor currently in development is ready.

Nor should the US limit this system to its own use. We’ve already partnered with Japan on Aegis BMD, installed Aegis Ashore in Romania and Poland and sold THAAD to the Saudis and the UAE, who used it to shoot down a missile in early 2022. Ensuring that these systems are widely distributed will not only allow us to spread the costs across a larger buy but also significantly decrease the impact of any potential nuclear conflict. The ballistic missile is a threat that can be mitigated, and for both strategic and humanitarian reasons, it should be mitigated.

1 Assuming, of course, that the number of warheads remains constant. This was probably the best argument against missile defense during the Cold War, when it was at least theoretically possible that the Soviets could double their arsenal in response to the threat. It’s a lot less feasible today, given arms control treaties and the shaky state of the Russian economy. It’s plausible that China could pull it off, but they’ve long taken a rather more minimal approach to deterrence than Russia has, which means a reasonable missile defense system probably wouldn’t worry them too much. Also worth noting that yes, it’s possible to overcome a 50% effective system by shooting two warheads at each target, but the number of targets is cut by 50% either way. ⇑

2 This shouldn’t be read as a strong defense of the technical merits of SDI as laid out in the 80s. It was definitely compromised by the need to work around the ABM treaty, and a great deal of what was proposed was intended to send the Soviets on a wild goose chase, spending money all the way. It’s not entirely clear what falls into that category, and what was serious. Reagan also seemed to push the “getting rid of nukes” position pretty hard, which I am less sure is a good idea. ⇑

- by bean

- 19 comment(s)

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK