The Smash and Grab of Kroger-Albertsons

source link: https://mattstoller.substack.com/p/the-smash-and-grab-of-kroger-albertsons

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

The Smash and Grab of Kroger-Albertsons

The Kroger-Albertsons supermarket deal is uglier than you might expect. The "special cash division" of $4 billion may be intended to get around antitrust enforcers.

Welcome to BIG, a newsletter on the politics of monopoly power. If you’re already signed up, great! If you’d like to sign up and receive issues over email, you can do so here.

Today I’m writing about a the merger of two supermarket giants, Kroger-Albertsons, with a focus on a weird wrinkle wrought by the private equity investors who are pushing for the deal.

Last week, supermarket chain Kroger announced it would be buying Albertsons for $24 billion, in the largest grocery acquisition in U.S. history. Kroger and Albertsons are both monsters, and the two of them combining would create the second largest chain in the country, after Walmart, with 15% of the national grocery business. Kroger/Albertsons would employ over 700,000 people, have over $200 billion in revenue and more than 40,000 private label brands, and own and operate brands such as Safeway, Ralphs, Smith’s, Harris Teeter, Dillons, Fred Meyer, Vons, Kings, Haggen, Tom Thumb, Star Market, Jewel-Osco, and Shaw’s.

There’s been a lot of good analysis of this deal already, so I want to focus on something a little unusual. The merging parties and their investors know that enforcers will challenge the deal. I mean, Albertsons will get $600 million from Kroger if the government blocks the deal, which is a reasonably sized break-up fee. This merger is no slam dunk, to put it mildly.

What I find weird is that, in just a few weeks, and long before any merger trial, Albertsons will hand up to $4 billion to its private equity investors Apollo Capital and Cerberus Capital Management, in a special dividend. That’s the cash and working capital necessary to keep a supermarket chain functional, gone, to the private equity investors, even if the merger falls through. And that’s worrisome.

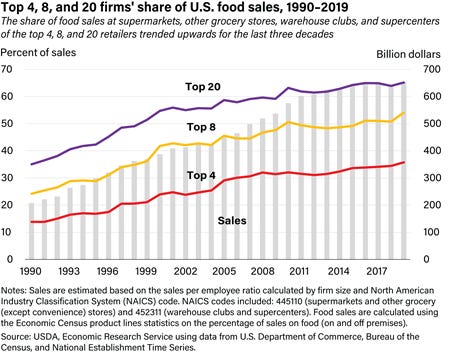

But before I delve into that, let’s talk about what this merger would do, and why it’s so important. The Kroger-Albertsons deal would be the capstone to a broader trend. Over the last thirty years, supermarket chains have consolidated the nearly $1 trillion grocery industry. It’s not just a big business, it’s a critical one - everyone’s gotta eat, and whether we eat healthy food or not is in many ways up to the dominant firms in the industry. This chart from the United States Department of Agriculture shows the broad centralizing trend, and though industry-wide mergers are common, the USDA also explicitly called out Kroger for its acquisitiveness.

There are three markets in which supermarkets operate. The first is at a national or regional level, as supermarkets buy from consumer packaged goods companies, meatpackers, and food processors, as well as use wholesalers and warehouses. The second is at a local level. Consumers shop where they live. If there are two stores in a city, there are only two competitors in that city, even if there are stores in other states. The third market is for supermarket and warehouse workers, and this too is local. People work where they live.

All of these different markets will come into play in this case.

There has been tremendous concentration on both a national and local level already. As Errol Schweizer at Forbes noted in an excellent piece published immediately after the deal came out, “There are already 30% fewer grocery stores than a few decades ago and most major metropolitan areas (with the exception of New York City) are heavily concentrated among just a handful of grocery chains.” That means large chains not only secure better prices for goods than their smaller counterparts, but can also increase prices faster than costs, contributing to inflation. Suppliers, consumers, and workers will all feel the pressure from Kroger/Albertsons, and since suppliers buy from farmers, farmers will feel it too, at least indirectly.

It’s hard to see an upside to this combination. There will be layoffs in white collar jobs such as “office-based marketing, procurement, analytics, digital sales and category management roles,” which the firm calls ‘synergies.’ Kroger will have more bargaining power over suppliers, as it will have 5,000 stores and can “more easily set payment terms, negotiate shelf space and assortment, and extract better costs and greater trade allowances for promotions, couponing, ad placement and slotting fees.”

In addition, deals like this concentrate grocery shelves with the goods of certain dominant firms in packaged foods categories, such as “Pepsico, Kraft Heinz, Nestle and Kelloggs, as well as meat and poultry barons such as Tyson, JBS and Smithfield, centralizing industrial agricultural supply chains.” This will further centralize the food supply overall and could potentially prevent the stocking of more seasonal and local food. Finally, Kroger and Albertsons are combining their data hoards and advertising network, which could be quite significant. Everything is a Big Tech deal when it comes to using data at scale for targeted advertising.

The logic for the deal rests on the idea that supermarkets are a business with tremendous economies of scale, and Kroger/Albertsons will use savings to lower prices for consumers. In any local market where the new firm would have too much of the market, it will simply sell some of its stores in a divestment. It has committed to spinning off up to 650 stores into a smaller firm, creating a new and vibrant competitor.

Of course, this deal makes no sense as anything but an attempt to increase market power. If there are true economies of scale at work, then spinning off competitive stores into a smaller firm will inherently fail. And this is indeed what we’ve seen, in perhaps the all-time most embarrassing merger approval plus divestment by the Federal Trade Commission under the Obama administration, which also took place in the supermarket business and involved Albertsons.

A previous merger involving Albertsons offers a cautionary tale to potential buyers. When Albertsons agreed to acquire peer Safeway for more than $9 billion in 2014, it subsequently won regulatory backing by signing a deal to sell 146 stores to West Coast regional grocer Haggen for $300 million. Haggen filed for bankruptcy months later and blamed the deal with Albertsons for its demise. Albertsons then agreed to buy many of the Haggen stores back for $300 million.

Amusingly, the law firm representing Kroger is Arnold & Porter, whose antitrust practice is headed by Debbie Feinstein, the Obama era FTC Bureau of Competition Director who actually approved the Albertsons/Safeway merger and its laughably stupid remedy.

What worries me most about this deal is the financial engineering that’s taking place up front. Albertsons is owned by Cerberus and Apollo, both of whom want to exit from their investment. Cerberus has owned a chunk of Albertsons for 16 years, which is an extremely long time for a private equity investor. It has helped grow Albertsons through acquisitions, including the Safeway merger, but recently has been frustrated with the poor performance of the firm’s stock relative to peers.

This deal strikes me as a desperate move. I don’t think it gets through the courts. The internal logic - economies of scale are great, though the small spinoff will totally work - is silly. And there are too many stakeholders, including suppliers, rivals, and unions, who are afraid of what Kroger would do with its power. Kroger is already under investigation by the FTC over supply disruptions. But deals like this can take a long time to fall apart. The FTC will have to investigate, which can take six months, and then file a complaint, go through a trial, and maybe an appeal. All told it’s nine to eighteen months before it resolves, one way or the other.

However, Cerberus and Apollo have set this deal up so that two weeks after the shareholder vote on October 22, shareholders take up to $4 billion from Albertsons in a ‘special dividend.’ This is a standard private equity move to shift cash from a portfolio company to investors. This won’t really help normal investors, who could just sell their shares if they want to raise cash. But it will help large shareholders like Cerberus and Apollo, who have so much of the stock that they can’t unload what they have on the market. Instead, they have to take the cash directly from the company rather than selling the company’s shares.

The problem is that in this case, that cash is pretty much all the liquidity that Albertsons has. According to the firm’s latest 10Q, Albertsons has $3.213 billion of cash and $565 million of receivables, which can be quickly sold to raise cash. There’s your special dividend right there.

BIG is a reader-supported newsletter focused on the politics of monopoly and finance. This is journalism and advocacy that challenges power, so please consider a paid subscription. You can always get lies for free. The truth costs a few bucks, but in the long run it’s much cheaper. You can subscribe by clicking here.

It worries me that all of the liquidity will be drained from the firm, as having no cash to draw on, combined with the uncertainty of the merger investigation, will immediately begin weakening the business. Over time, Albertsons executives will begin to claim to the judge that it must be allowed to merge, since it is a weakened party and only Kroger’s acquisition can save it. But of course, it will have weakened itself, or more accurately, Cerberus and Apollo will have weakened it. It’s a bit like a private equity firm blood-letting someone after buying the person a life insurance policy the private equity firm then gets to collect. It’s not a great incentive system. (I hesitated before writing this analogy, I didn’t want give the PE industry any ideas.)

I don’t know if it’s possible to use the antitrust laws to file for an emergency injunction over this special dividend, since one could argue it’s a restraint of trade or a mechanism meant to substantially lessen competition. Or maybe I’m missing something about the deal. But if not, then arson, as long as it’s done via private equity, is legal. Or as the Onion put it…

Thanks for reading!

And please send me tips on weird monopolies, stories I’ve missed, or comments by clicking on the title of this newsletter. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation and democracy. And consider becoming a paying subscriber to support this work, or if you are a paying subscriber, giving a gift subscription to a friend, colleague, or family member.

cheers,

Matt Stoller

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK