Effing the Ineffable: A Writer Takes Psilocybin.

source link: https://medium.com/@markdery/effing-the-ineffable-a-writer-takes-psilocybin-a3ee6bb1eae8

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Effing the Ineffable: A Writer Takes Psilocybin.

I took magic mushrooms in hopes of curing my existential malaise. Instead, the mushroom gave me a master class in the alien strangeness of language, and how even writers are at war with words.

(Part Four of a four-part essay. Part One, “The Thing in the Mirror,” is here. Part Two, “’I is an Other’: The Self is a Gothic Fiction,” is here. Part Three, “A Medicine for Melancholy,” is here.)

What didn’t happen, last year, when I ingested five dried grams of Psilocybe cubensis: an audience with “the self-transforming machine elves of hyperspace” like the one Terence McKenna, the cracked Shackleton of neuronautical exploration, had when he took the potent tryptamine hallucinogen DMT. The drug teleported McKenna to the bejeweled, dizzily tessellated sanctum of the “tryptamine entities” but they weren’t home the unseasonably sunny October morning I came knocking. (Then again, I’d taken magic mushrooms, longer-lasting but not nearly the Large Hadron Collider for the mind DMT is reputed to be.)

Nor was I, like Thomas De Quincey in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, “buried for a thousand years in stone coffins, with mummies and sphinxes” or “kissed with cancerous kisses by crocodiles and laid, confounded with all unutterable slimy things, amongst reeds and Nilotic mud” (Charles Baudelaire, “An Opium-Eater”).

Unlike Michel Foucault, tripping on LSD at Zabriskie Point in Death Valley, I wasn’t granted a vision of the machinery of night gone haywire. “The sky has exploded and the stars are raining down upon me,” the philosopher told one of his companions. “I know this is not true, but it is the Truth” (Simeon Wade, Foucault in California). (I was, after all, wearing an eye mask to screen out distracting sensory input and direct my mental attention inward.)

More to the point, I didn’t experience “ego death.”

Roxy Paine, “Psilocybe Cubensis Field” (1997), The Feldman Gallery.

Taken in sufficiently large doses, psychedelics like psilocybin dial down activity in the default mode network, a command center in the brain some neuroscientists believe is the ego’s HQ. The result, in many cases, is a controlled (and, I hasten to add, short-lived) demolition of the sense of self, colloquially known as “ego death.”

Researchers working in the promising new field of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy (popularized by Michael Pollan’s bestseller How to Change Your Mind) believe that the temporary liquefaction of an ego that has hardened into a rigid, obsessively ruminative, self-defeatingly defensive drill instructor creates a psychological — and neurological — window of opportunity for rewriting the stories we tell ourselves about who we are.

“When the grooves of self-reflective thinking deepen and harden, the ego becomes overbearing,” writes Pollan.

This is perhaps most clearly evident in depression, when the ego turns on itself and uncontrollable introspection gradually shades out reality. [The psychologist and neuroscientist Robin] Carhart-Harris … believes that people suffering from a whole range of disorders characterized by excessively rigid patterns of thought — including addiction, obsessions, and eating disorders as well as depression — stand to benefit from “the ability of psychedelics to disrupt stereotyped patterns of thought and behavior by disintegrating the patterns of [neural] activity upon which they rest.”

This is Your Brain on Psilocybin. Diagram from Michael Pollan’s “How to Change Your Mind” showing new neural connections stimulated by psilocybin, the active ingredient in Psilocybe cubensis (“magic mushrooms”). Pollan writes, “The finding … that the psychedelic experience leads to long-term changes in the personality trait of openness raises the possibility that some kind of learning takes place while the brain is rewired and that it might in some way persist.”

I’d taken Psilocybe in hopes of attaining escape velocity from the existential malaise and low-lying fog of weltschmerz that had shadowed me for much of my life but also because I wanted to know — no snickering, please — whether existence means anything, naïve as that sounds.

In a nation traumatized by a full-blown mental-health crisis, the psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy described by Pollan holds bright promise for the millions who suffer from disorders like anxiety and depression. But it may be a balm, too, for those of us whose agonies of mind have more to do with Man’s Search for Meaning in a Godless Cosmos than the “mood disorders” catalogued in the DSM.

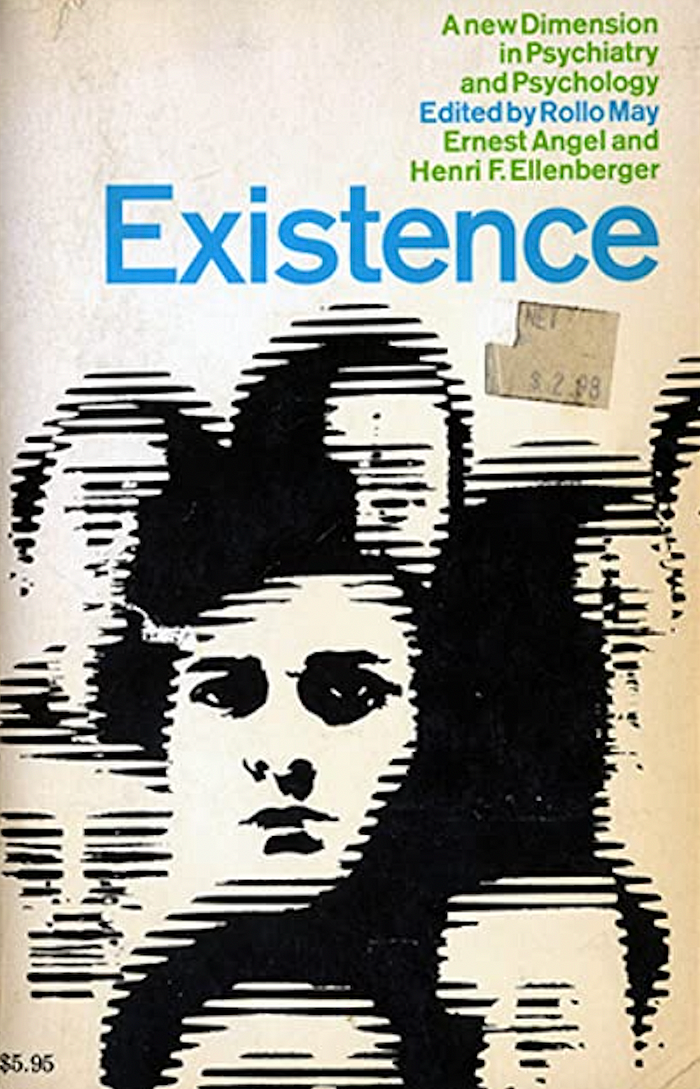

Beckettian emptiness can’t be explained away as a matter of serotonin deficiency. Often, it’s a consequence of the angst and alienation that Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Samuel Beckett wrestled with in their novels, plays, and philosophical writings (and which the existential psychotherapy of Rollo May and Viktor Frankl sought to treat, on the assumption that anxiety is part of the human condition).

For those whose afflictions are more existential than neurochemical, an ego-vaporizing dose of Psilocybe, assisted by philosophy (and paired, if need be, with the Talking Cure), just might be the answer to existentialist prayers. Now is the time for the owl of Minerva — philosophy, in Hegel’s hauntingly beautiful metaphor — to take flight. Psychedelics can be its tailwind.

But we were talking about my ego’s refusal to flatline.

Five dried grams — the fabled “heroic dose” prescribed by McKenna — should’ve done the trick. Maybe the mushrooms had lost their potency during the months they’d lain in my desk drawer (against a more experienced friend’s admonitions to keep them in the freezer). Maybe my ego, buttressed by a sharply defined sense of self and bristling with the perimeter defenses of an only child who resolved, early on, that each man is an island, required a bigger dose to blow its house down.

Which isn’t to say my attempt at grafting philosophical investigation onto psychedelic therapy came to naught.

My default mode network’s refusal to cede control resulted in a trip that felt less like the wrenchingly emotional catharsis experienced by the research participants quoted in How to Change Your Mind and more like a philosophical dialogue with the tutelary deity of Psilocybe odysseys. Or maybe it was a brain-tennis volley between the two faces of my janiform self: my ironizing, deconstructing, linguistically tricksy, perpetually “meta” side and my more emotionally attuned, psychologically minded, self-dissecting half.

Either way, my trip was profoundly “writerly,” preoccupied with questions like: What are the limits of language? What is language’s role in mediating our lived worlds and authoring the selves we inhabit? And: is language “a virus from outer space,” to quote the avant-pulp novelist William S. Burroughs (whose declared objective was to “rub out the word” — and silence the Narrative Self — through his patented “cut-up” method of literary collage)?

Not that you’d have known this if you’d been watching a video feed from my visual cortex. Propped up in bed with pillows, eyes closed behind my slumber mask, I spent most of my trip banking and swooping and soaring, like one of those GoPro-helmeted wingsuit flyers, through a Victorian opium dream rendered in Jack Kirby’s comic-book Baroque — a never-ending, eerily depeopled megalopolis, ancient yet futuristic, extraterrestrial but somehow Moorish and Mughal, its obelisks and pleasure domes, Mandelbulbs and minarets gilded by the sun.

Jack Kirby, “The Eternals” (Marvel Comics).

Dr. Wu (not her real name, obviously), the therapist I’d spent months working with on my flight plan — my psychotherapeutic and philosophical goals — had recommended I record my impressions and insights immediately after my trip ended, before they melted away. Determined to preserve the untrue Truths of my trip, as Foucault might say, I’d begun scribbling even as I made my final approach to everyday reality. At that point, the effects of the drug were reduced to an opalescent shimmer at the edges of things — I’d taken off the eye mask by then — and a subtle billowing: the books on the shelf across the room appeared to be breathing, their spines bulging outward, then contracting (in time with my own inhalations and exhalations, I soon realized).

Filling 25 pages in my trip diary, my stream-of-consciousness jottings are a record of my linguistic mind’s attempts to jump over its own shadow — to use language to think outside language.

You’re thinking, But wait: Isn’t this just the Narrative Self doing what it does — reducing the irreducible to little black marks marching across the page? “To put words to an experience that was in fact ineffable,” writes Pollan, after recounting his own experiences on psilocybin, “and then to shape them into sentences and then a story, is inevitably to do it a kind of violence.” Even so, he adds, “the alternative is, literally, unthinkable.”

Trapping our swarming thoughts in its butterfly net and pinning them to the page, language gives us the illusion of effing the ineffable. But with every translation a world of meaning is lost. “Once you got words you thought the world was everything that could be described, but it was also what couldn’t be described,” writes Edward St. Aubyn in his novel Mother’s Milk, channeling the thoughts of a little child entranced by his newly acquired plaything, language. Still, as Pollan notes, it’s all we have.

Trying to capture my experience in words, I was poignantly aware that the power to put names to things, which gives language its ability to conjure worlds out of thin air and link minds telepathically (as ours are linked now), is also what limits the thinkable to the sayable, and renders the unsayable ungraspable.

With hindsight, my videogame flyover, which had continued in one long uneventful tracking shot for the better half of my trip, looked like my brain’s way of distracting my visual cortex with a bright, shiny bauble while my default mode network got down to philosophical business. As one part of my mind savored the giddy pleasures of a drone’s-eye-view of a Venusian Xanadu, or Antoni Gaudi’s take on the dead cities of Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles, or whatever it was, my linguistic mind was moderating a Socratic dialogue between two disembodied viewpoints, neither wholly “me,” about the uncanniness of language and the Otherness of the Narrative Self; the demiurgic power of words and the ways they cage thought and circumscribe our worlds.

An unthought thought popped into my head: You’re talking to yourself in your mind, it said, teasingly, doing running commentary on your trip. Another observed, Isn’t there something disquieting about language, something that makes us ambivalent about it, spellbound but mistrustful?

“We are engaged in a struggle with language,” Ludwig Wittgenstein declared. Flying past Blade Runner megastructures and Cyclopean ziggurats, an unthought thought recalled his Philosophical Investigations. “Philosophy,” he wrote, “is a struggle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language.”

The early Wittgenstein — the Spock-like logician of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1922) — struggled to pin language, his wriggly opponent, to the wrestling mat of scrupulously factual assertions about the world. The effable world, for Wittgenstein, is “the totality of facts,” nothing more. We must set aside questions that lie beyond the scope of science (such as, “What is the meaning of life?”), not because they’re meaningless or trivial but because they can’t be expressed in language. “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent,” he says, with case-closed finality, at the end of the Tractatus.

Yet here he is in 1933, in Philosophical Occasions, placing his faith in language, or at least in philosophical language: “The philosopher strives to find the liberating word; that is, the word that finally permits us to grasp what up to now has intangibly weighed down upon our consciousness.”

Ludwig Wittgenstein, 1930. Moritz Nähr — Austrian National Library.

Martin Heidegger, the existential phenomenologist, thought about language, too (when he wasn’t brooding about death). In “The Way to Language,” he argues that language “concerns itself purely with itself alone,” a darkly mysterious claim by which he means (or seems to mean — penetrating Heidegger’s Black Forest mysticism can be thorny) that language, considered as language — that is, outside the anthropocentric worldview, which sees it only as a communications medium between humans — has its own agenda. “Language speaks,” says Heidegger. You speak, I speak, but it is language that does the speaking (so to speak).

What does language say when it speaks? It says this is and that is. It points at things. But not just any thing: silently, subtly, yet no less coercively, language directs our attention to that which is sayable. Language “shows what is there to be spoken about,” says Heidegger, “and thereby allows things to either appear or disappear from view.”

Language speaks. “The Abyss” (1989), directed by James Cameron.

There’s a scene in James Cameron’s otherwise forgettable SF film The Abyss (1989) that, if we read it as a parable about our relationship with language, provides a sublime illustration of Heidegger’s point. On a drilling rig far beneath the ocean’s surface, an undulating tentacle of seawater, puppeteered (or possessed?) by the “non-terrestrial intelligences” who dwell in the abyssal depths, snakes through the rig’s compartments. At first, the crew is terrified, but soon they’re reduced to childlike wonder at the sight of the silvery, luminous appendage morphing into the faces of first one, then another crewmember, mirroring their features with uncanny accuracy. “It’s trying to communicate,” exclaims the awestruck scientist. Playfully, she sticks out her tongue, and the alien technology (or is it an entity?), wearing her face, mimics her flawlessly.

Language, in the guise of a giant, prehensile tongue, speaks. (The word derives, we recall, from the Latin lingua, for “tongue.”) The mother of all mother tongues, language is the ur-technology, the “extension of man” (Marshall McLuhan) that made humankind. We created language, but language, in a very real sense, created us. “The essence of man consists in language,” says Heidegger. “We are within language, at home in language, prior to everything else.” Because we possess language, we’re not just the only animal that speaks, we’re the only one that can ask, “What is the meaning of life?” It’s language, says Heidegger, that makes meaning possible. “It lets what is coming to presence” — that which stands out against the background noise of our lived worlds as meaningful — “shine forth.”

Yet language remains somehow alien, uncanny. We speak through language, but the medium has its own message, above and beyond whatever I say, whatever you hear. (“What is spoken, is never, in any language, what is said,” writes Heidegger, cryptically.)

And, just as we can’t stand on our own heads, we can’t use language to penetrate the mystery of language. “We human beings, in order to be who we are, remain within the essence of language,” writes Heidegger. “We can therefore never step outside it in order to look it over circumspectly from some alternate position.” More profoundly, we can’t think outside thought, a truism that fills me with infinite sadness.

At this point, near the end of my trip, I noticed my face was wet with tears, though I had no recollection of when I’d started — or stopped — weeping. “What did I learn?” my trip diary asks. I’d come looking for a cure for existential melancholy and — in my dreams — some answers to the philosophical questions that had plagued me since my Summer of Angst in 1976, when at age 16 I experienced an Existential Crisis of Meaning. “I remember thinking, near the end of my trip, that I’d been seeking something all my life, only to realize that the mushroom’s revelation was that this is all there is. There’s no subtext because life isn’t a text, and the very notion of a ‘Meaning of Life’ is self-parodically Monty Pythonian.” Sartre, speaking through Roquentin in Nausea, had been right all along: “Things are entirely what they appear to be — and behind them … there is nothing.”

Late in the afternoon of a long day, I came to rest in my backyard, seated in a lawn chair facing the bamboo trees that stand sentinel along the fence. I felt like a neuronautical version of Lawnchair Larry, the guy who’d attached a cluster of helium-filled weather balloons to a patio chair, ascended to cruising altitude, and, against all odds, touched down in one piece.

I thought about my lifelong love affair, as a writer, with language; how the witchcraft of words thrills me while, at the same time, the outer limits of language entice me, make me wonder: what’s behind the curtain that separates the sayable from the ineffable? Profundity? Or the void?

I thought of Samuel Beckett’s remark, to a friend, that language seemed increasingly “like a veil that must be torn apart in order to get at the things (or the Nothingness) behind it. … As we cannot eliminate language all at once, we should … bore one hole after another in it, until what lurks behind it — be it something or nothing — begins to seep through.”

Yet the same man once wrote, “Words were my only love.”

To be human is to seek out patterns; to make meaning. In his essay collection Bald, the philosopher Simon Critchley offers an existentialist homily: “Human beings have been asking the same kinds of questions for as long as there have been human beings to ask. It is not an error to ask. It testifies to the fact that human beings are rightly perplexed by their lives. The mistake is to believe that there is an answer to the question of life’s meaning.”

In his magnum opus, Being and Time, Heidegger gives us a mocking paradox: it is only by “being-unto-death” — facing the inevitability of our mortality and acting accordingly — that we’re able to live meaningfully, yet that coming nothingness renders all our meaning-making absurd.

Still, we can’t not make meaning.

At 16, in 1976, I hadn’t read Heidegger. I didn’t know that my existentialist epiphany about the inherent meaninglessness of the world wasn’t a life sentence to the Absurdist limbo of Waiting for Godot; that it could be a kind of liberation. We are, as Jean-Paul Sartre put it, “condemned to be free.” We’re “thrown” into this world, as Heidegger says, and the instant we’re born the clock of our mortality starts ticking. There’s no meaning in this life but what we make of it.

Intentionally or not, Laurie Anderson expresses these thoughts beautifully in her song-poem “Born, Never Asked,” which I’ve always heard as an existentialist hymn:

It was a large room. Full of people. All kinds.

And they had all arrived at the same building

At more or less the same time.

And they were all free. And they were all

Asking themselves the same question:

What is behind that curtain?

You were born. And so you’re free. So happy birthday.

Disclaimer: As Michael Pollan notes in How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence,“It is a criminal offense in the United States and in many other countries, punishable by imprisonment and/or fines, to manufacture, possess, or supply LSD, psilocybin mushrooms, and/or the drug 5-MeO-DMT, except in connection with government-sanctioned research.” This essay, like Pollan’s book, chronicles the author’s experiences with psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. It is intended as a philosophical investigation, not an exhortation to lawbreaking. The author (borrowing more of Pollan’s boilerplate) “disclaims any liability, loss, or risk, personal or otherwise, that is incurred as a consequence, directly or indirectly,” of the contents of this essay or its previous installments.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK