Codebase as Database: Turning the IDE Inside Out with Datalog

source link: https://petevilter.me/post/datalog-typechecking/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

2020-7-17

tl;dr: I made a prototype IDE in which language semantics are specified in datalog, powered by a datalog interpreter written in TypeScript, running the browser.

Motivation

What is an IDE?

When we write code, we’re not just writing text — we’re weaving together a web of names or “symbols” whose definitions reference each other. See, for instance, this small example, which defines variables and then uses them in a later expression:

Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) help us to interrogate and manipulate this web of symbols (which I'll call the reference graph), through several key features:

- Highlighting and jumping between usages and definitions allows quick exploration of the reference graph.

- Semantic code completion helps explore what's in scope, save typing, and avoid typos.

- Renaming a symbol and all its usages enables refactoring with confidence.

- Inline compile errors let us quickly see and fix type errors in context.

- Many others, like call and type hierarchies, help gain an overview of a codebase.

These features have one thing in common: they depend on the IDE’s internal model of the codebase, which it is constantly keeping up to date as the user edits files:

Thus, IDEs, are, at their core, platforms for facilitating the circular dataflow above:

- When the user edits the code, the IDE updates its internal model of the codebase according to language-specific rules.

- When the user requests an action (e.g. renaming a symbol, or jumping to a definition), the IDE queries its internal model to get the data needed by the action (e.g. the locations of the usages and definitions of the symbol in the source) and then makes the edit or navigates to the requested location.

The Potential: Introspectable, Easily Extensible IDEs

In my experience as a programmer, these features have been indispensable while working on large codebases. But as I’ve used IDEs more, I’ve often felt that they have unreleased potential, because this rich internal model of the codebase is locked up within them, inaccessible except by painstakingly writing plugins using IDE-specific APIs. I’ve been wondering: what if this codebase model was as queryable as a database is? What new questions would we ask of our codebases, and what new ways would we find to visualize them? Furthermore, what if the language semantics themselves — types, completions, errors, etc — were specified as queries, which were also introspectable?

I believe that the design of languages and programming environments should not just be the province of a small priesthood of elite developers. Everyone should be able to look under the hood of their IDE, and be free to push its boundaries: embed it in a different context, create a domain-specific language with rich editor support, fork an existing language to play with its semantics, etc.

The opacity of the IDE’s inner model — and the rules by which that inner model is updated — are barriers to this being a reality. For IDEs to be introspectable and hackable, we must first expose this model and these rules: we must turn the IDE inside out.

Limitations of Current IDEs

So, what exactly does this mysterious codebase model data structure look like? How do existing IDEs keep it up to date, and how do they use it to power their UIs? What are the limitations which developers face when trying to add support for a language to one of these IDEs?

My usual IDE, IntelliJ IDEA, defines its codebase model as an intimidating hierarchy of Java classes called the PSI, or “program structure interface”. Its plugin editor allows language extension developers to build parsers for their language, which parse source code into “PSI nodes”. Other Java code then runs to annotate these PSI nodes with types and other information, and then other code — “completion providers,” for instance — runs over this structure to provide completions and other IDE features.

While this architecture has allowed JetBrains to add support for an impressive number of languages to the IntelliJ platform over the years, it doesn’t pass the test of introspectability and hackability: the PSI tree can be viewed, but not queried, while the IDE is running, and the languages' typechecking and completion logic can’t be introspected or edited at runtime; one has to track down the Java sources of a given language’s plugin, if it’s open source.

Microsoft’s Visual Studio Code attempts to ease the creation of language extensions with the Language Server Protocol, which allows language extension developer to implement language support as a server which VSCode calls into for completions, type errors, and other information which it then renders to its UI.

This architecture has the benefit of allowing language extensions to be written in any language, thus allowing them to share code with the languages’ native compilers, which lowers the barrier to entry for adding support for new languages. And, the messages sent back and forth over this protocol are a good introspection point, which could help a developer understand and debug a language extension. Still, I believe this architecture doesn’t go far enough toward the goals of introspectability and hackability, since the codebase models that language extension servers use to respond to the IDE’s requests are still locked up inside the servers, accessible only via a complicated low-level API, not arbitrary queries.

A New Approach: Codebase as Database

So, I was left wondering: is there a simple, elegant data structure and computational framework which can be used as the foundation of an IDE? It would ideally have these properties:

- Incrementality: The ability to efficiently respond to user changes by recomputing only the results which are affected by those changes. Ideally language extension authors should not have to think about this; the IDE should do it “for free” once the authors have expressed their language semantics in its framework.

- Ad-hoc queryability, (aka access-path independence): The ability for language extensions or IDE users to evaluate arbitrary queries against any internal data structure at runtime. The IDE should allow these queries to be expressed logically, and find the optimal way to execute them based on the indexes available. This is especially important because many IDE features, such as “find usages” and “go to definition” or “find implementations” and “go to interface” can be seen as one relation, queried from two different directions. Jordan Scales’ post “functions that go backwards” elaborates more on this perspective.

- Traceability: The ability to follow a result (for instance, a type error or a completion) back through the language’s inference rules to base facts about the program’s AST. The IDE user should be able to see all of the reasoning behind what the IDE is telling them.

As a database nerd (I was working at Cockroach Labs as these thoughts started to percolate), this started to look like a database problem to me. If a codebase could be represented as a relational database — that is, rows in a set of interlinked tables — it seemed possible to achieve all three of the requirements above: the tables would be inherently introspectable, and with the right query language and engine, perhaps all IDE features could be powered by queries on those tables, which could be kept up to date efficiently by the engine. Essentially, the problem of IDE infrastructure could be reduced to the problem of incremental view maintenance.

This perspective was promising, but the traditional database language — SQL — seemed to be an awfully clunky way to express complicated concepts like type inference rules. Thankfully, SQL has a cousin, Datalog, which is more suited for the task.

Interlude: Brief Intro to Datalog

The universe of a datalog database (sometimes known as a "deductive database") consists of two things: facts and rules. (This places it in the paradigm of “logic programming”, alongside its cousin Prolog).

Facts are statements we tell the database are true, like simple INSERT statements into a SQL database. Here we're inserting one row into the mother table, and one into the father table:

mother{child: "Pete", mother: "Mary"}.

father{child: "Mary", father: "Mark"}.

Rules infer new facts from existing facts. They use variables (conventionally capital letters), and two operators: | (or) and & (and):

# read as "C's parent is P if C's mother is P or C's father is P"

parent{child: C, parent: P} :-

mother{child: C, mother: P} |

father{child: C, father: P}.

# read as "A's grandfather is C if A's parent is B and B's father is C"

grandfather{child: A, grandfather: C} :-

parent{child: A, parent: B} &

father{child: B, father: C}.

Rules can reference both base facts and other rules.

Queries look like facts, but have some variables in them:

grandfather{child: "Pete", grandfather: C}.

My interpreter returns query results as "trace trees", which show the final result as the root node at the top (in this case, my grandfather), with contributing facts and rules as child nodes. A node with two child nodes represents its children being &-ed together; leaf nodes are base facts.

grandfather{child: A@"Pete", grandfather: C@"Mark"}; {A: A, C: C}

parent{child: A@"Pete", mother: B@"Mary"}; {C: A, P: B}

mother{child: C@"Pete", mother: P@"Mary"}

father{child: B@"Mary", father: C@"Mark"}

Through these simple language mechanisms — facts, rules, queries and traces — datalog provides a computational framework which satisfies our goals of ad-hoc queryability and traceability. Whats more, some datalog interpreters, such as VMWare’s Differential Datalog, provide incrementality out of the box.

Implementation

To test the validity of this idea, I wrote a datalog interpreter in TypeScript, and built a prototype introspectable IDE around it.

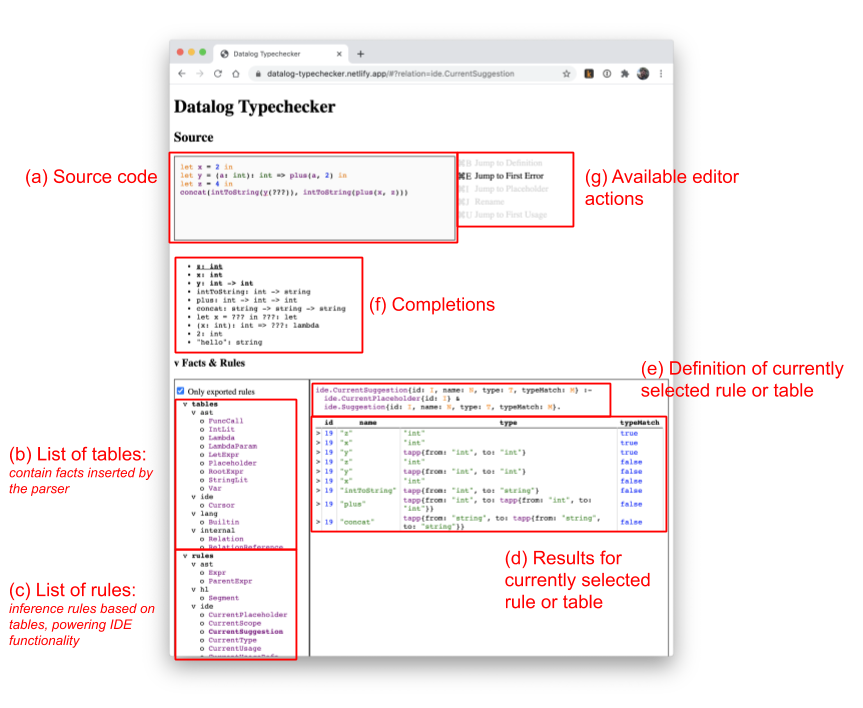

The IDE currently only supports a made-up simple functional language which I call “FP”, which consists only of let expressions, lambdas, function calls, and string and integer literals, although the goal is for new languages to be easy to add. Its UI looks like this:

The user types source code into the box (a). A parser then turns it into an AST, which is then “flattened” into a set of facts in tables (b). Inference rules (c) are defined on these facts. Their definitions (e) and results (d) can be introspected. These inference rules are then queried by the IDE to provide its features, including (f) completions, (g) other actions, such as jumping and renaming, and syntax highlighting.

The following is a worked example of this process (with slightly simplified datalog rules) for a simple expression.

Step 0: Flatten

Before the fun with Datalog can begin, we have to parse the code into a syntax tree, and then flatten that syntax tree into rows into relational tables, which will comprise our set of facts.

FP only has a few syntactic constructs:

- string and integer literals

- let expressions

- lambdas

- function calls

We'll start with a let expression. This let expression:

let x = 2 in x

becomes this AST:

Let(x)

/ \

2 Var(x)

We then assign an ID to each AST node:

0:Let(x)

/ \

1:2 2:Var(x)

and use these IDs to “flatten” the nodes into rows in tables which reference each other:

let_expr:

| id | var | binding_id | body_id |

|---|---|---|---|

0 | x | 1 | 2 |

int_lit:

| id | value |

|---|---|

1 | 2 |

var:

| id | name |

|---|---|

2 | x |

Step 1: Types & Scope

Now that we have our facts, we're ready to write some rules to infer things about them. Let's start with typechecking.

type{id: I, type: T} :-

type_int{id: I, type: T} |

type_var{id: I, type: T} |

type_let{id: I, type: T}.

The type of an int node is always the same:

type_int{id: I, type: "int"} :-

int_lit{id: I}.

Getting the type of a variable requires looking up its name in the scope:

type_var{id: I, type: T} :-

var{id: I, name: N} &

scope_item{id: I, name: N, type: T}.

Which requires us to introduce the scope_item rule:

scope_item{id: Body, type: T, name: N} :-

let_expr{binding_id: Binding, body_id: Body, var: N} &

type{type: T, id: Binding}.

Once we have this, we can write type_let, which gives us the type of the whole let expression:

type_let{id: I, type: T} :-

let_expr{id: I, body_id: B} &

type{id: B, type: T}.

This setup is a bit interesting because type and scope_item are a mutually recursive. Thankfully, that just works!

Typechecking other language constructs like function calls and lambdas is a bit tricker (but not much); see the full typechecker source on GitHub.

Note that there's a weakness here in the datalog approach: I haven't yet figured out how to make this typechecker give good type / scope errors, e.g. for a missing variable; it currently just returns an empty result set if one link in the chain of inference is missing. This is typical datalog behavior, but to give good type errors the language may need to be extended with a notion of "error hints", through which messages can be specified which will bubble up through the trace tree if a certain clause does not match.

We can now query our database for the type of a node:

> type{id: 0, type: T}.

type{id: 0, type: "int"}.

Step 2: Completion

The rules above also let us query for what's in scope at a particular node in the AST:

> scope_item{id: 2, type: T, name: N}.

scope_item{id: 2, type: "int", name: "x"}.

Can we use this to our advantage to power the IDE's autocomplete feature?

First, we need a way of indicating where in the AST completions are needed. In many real world cases, such as let x = 2 in <cursor>, there's a complication: until something is inserted at the cursor, the syntax is not valid, and won't parse with a conventional parser. Real IDEs address this with an error-recovering parser, which can extract a syntax tree and indicate the position of the cursor within it even when there are parse errors. (See an example explanation of how this works in this talk.)

I opted to avoid the complexity of error-recovering parsing for the time being by introducing explicit placeholder syntax into the language. For example:

let x = 2 in ???

The ??? becomes a placeholder node in the AST, flattened into its own placeholder table.

We can then write a simple rule which gives scope-based completions:

suggestion{id: I, type: T, name: N} :-

placeholder{id: I} &

scope_item{id: I, type: T, name: N}.

Now, how do we get the "current" placeholder; i.e. the one which the cursor is currently on? First, we'll insert a cursor fact (1-row table), which the IDE will keep up to date when the cursor changes:

cursor{idx: 42}.

To know how the cursor position relates to our AST nodes, we'll need to add a column with source location information from the parser into the tables representing our AST nodes:

placeholder:

| id | span |

|---|---|

2 | span{from: 10, to: 13} |

Once we have that (and creating an expr rule which incorporates location information from all expression types), we can write a rule which supplies the suggestions at the cursor:

current_suggestion{name: N, type: T} :-

cursor{idx: CIdx} &

scope_item{id: I, name: N, type: T} &

expr{id: I, span: span{from: FIdx, to: TIdx}} &

FIdx <= CIdx & CIdx <= TIdx.

(This shows a bit more syntax: binary operators. Currently there's only <=, ==, and !=!)

The real implementation defines another rule called expected_type (source on GitHub), which the IDE uses to prioritize suggestions which match the type which is "needed" at the current location — i.e. if we have

let x = 2 in let y = "hello" in plus(x, ???) # where plus : int -> int -> int

…the IDE will recommend both x and y, but highlight x because it has the right type for the function argument.

Step 3: Syntax Highlighting

If we add source location information to the AST node facts produced by the parser/flattener, we can define a relation of “segments” (often known as “tokens") in the source code, each with a type and a location:

segment{type: T, loc: L} :-

segment_int{type: T, loc: L} |

...

segment_int{type: "int", loc: L} :-

int_lit{loc: L}

...

Each segment type can then be mapped to a color.

(Implementation note: I used https://github.com/satya164/react-simple-code-editor, with small modifications, as a simple code editor which allowed me to implement syntax highlighting with a datalog-powered function).

The real reason to power syntax highlighting with datalog (as opposed to a more conventional tokenizer) is that it allows us to do semantic highlighting: for instance, highlighting all usages and the definition of the symbol which the cursor is currently on. This is done by first defining a usage relation:

usage{definitionLoc: DL, name: N, usageLoc: UL} :-

var{id: I, location: UL, name: N} &

scope_item{id: I, location: UL, name: N}.

And then adding clauses to the segment relations which specify that the segment should be highlighted if the cursor is within a usage or definition span.

Step 4: Refactors

Once we can query for a variable's definition and usages, it's a quick addition to allow the IDE to rename that variable. We first query the database to find the source spans of the definition and all usages, then do a string replace of those spans with the new name. This is achieved in a few dozen lines of TS. The implementations of jumping a symbol’s definition or usages are similarly small.

The Result

The result is a passing imitation of a real IDE:

Evaluation

Does this approach hold promise?

The goal of this prototype was to achieve parity with basic IDE features, while demonstrating the increased introspectability of a datalog-based system.

It does demonstrate these benefits:

- Incrementality: not yet; the interpreter is naive and recomputes everything from scratch on each keypress. This makes it slow on even fairly small strings of code. Yet, there are known techniques to incrementalize datalog interpreters.

- Ad-hoc queryability: Yes, rules are written logically and are queried from multiple directions

- Traceability: Yes, you can expand every result to see a trace

But, Has it achieved parity with existing IDEs?

- Realistic language features: not yet; the language is very simple.

- Performance: not yet; the IDE only works on small files.

- Actions: Pretty much — definition/usage jumping, renaming, and highlighting work nicely.

- Type errors: not yet: the IDE puts a red underline under AST nodes that don’t typecheck, yet it doesn’t explain why.

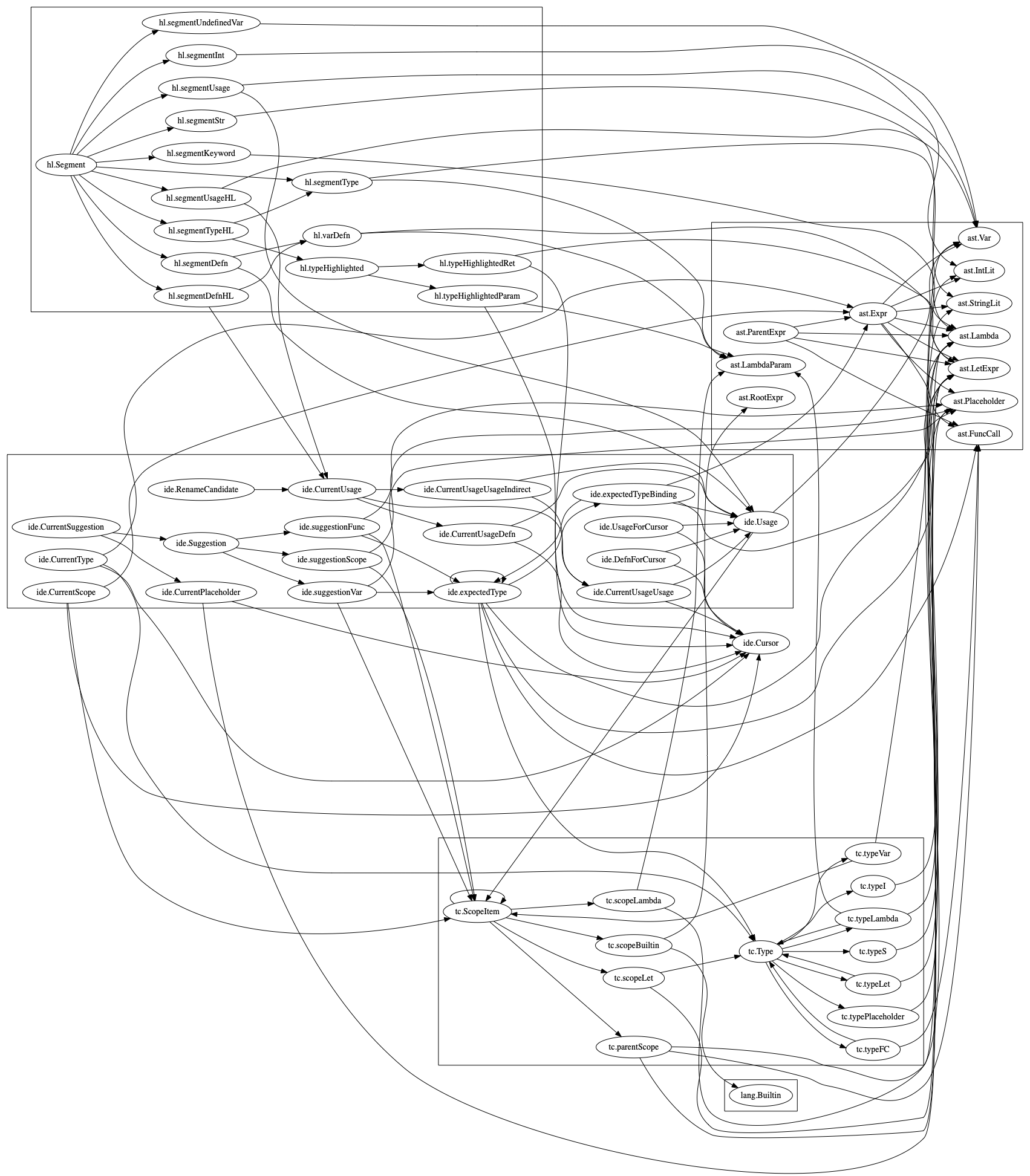

As an added bonus, the graph of rule dependencies (extracted using virtual tables exposed by the interpreter) ended up looking like this:

Future work

If this is to be an approach used in real tools and not just a toy, work is necessary on multiple fronts:

Performance: Upgrading the interpreter to be incremental or use indexes should make it scale to much larger codebases. Plenty of research on query optimization and incrementality exists which can be leveraged here.

Type errors: The biggest semantic issue with a datalog-based typechecker is that when no rules match, it returns an empty result set instead of an explanation of what went wrong. I haven’t found a precedent for dealing with this in vanilla datalog; it seems like some kind of extension to the interpreter is necessary to make it return “near miss” traces: traces which say what additional facts would be necessary to make a rule match.

Perhaps the Jetbrains MPS system, which allows specification and debugging of rule-based type checkers, can provide guidance here.

Language features: I want to see how easy it is to add more advanced features to FP, like generics, custom type definitions, etc. I expect these to stress test my datalog dialect, which is currently quite simple.

Visualizations: Since half the point of this effort is introspectability, I’d love to build more visualizations into the UI (such as DAGs, via Graphviz), which could be configured to visualize any relation.

Runtime modifiability of language syntax & semantics: The prototype currently has a hardcoded parser (in TS, using the Parsimmon library), and requires a build step to incorporate changes to it or the datalog rules. I’d love for these both to be modifiable at runtime in the IDE, allowing truly immediate language hacking. Whats more, the editor for grammars and datalog rules (syntax and semantics specs, respectively) could be powered by the datalog tooling as well.

I’m optimistic that, with lots more work, this system can grow into at least a helpful exploratory and educational tool, if not industrial-grade IDE infrastructure.

Related Work

- Compiler & IDE infrastructure

- IntelliJ Platform (Jetbrains; multiple languages)

- Jetbrains MPS: An environment explicitly aimed at creating new languages with IDE support; far more sophisticated and heavyweight than what’s presented here.

- Roslyn (Microsoft; C# and Visual Basic). See Anders Hejlsberg’s architecture talk

- Rust Chalk: A prolog-ish interpreter being used as the new implementation of the Rust compiler’s trait system. See this post by Niko Matsakis.

- This post on query-based compilers

- Martin Odersky (Scala): “Compilers are Databases”

- (Update 10/5) Glamorous Toolkit: An IDE focused on enabling custom visualizations and editors. Their philosophy, called "moldable development", is very similar to the one expressed in this post.

- Other tools:

- IncA: a datalog-based incremental program analysis framework

- CodeQL: A query language for ASTs, including at the level of types and dataflow, intended for statically finding security vulnerabilities.

- Eve: An attempt to reinvent programming which went through many iterations, the latest of which was a model inspired by datalog and relational programming.

Also, the title of this post is a reference to Martin Kleppman's classic talk Turning the Database Inside Out, which has similar themes of unbundling and incremental view maintenance.

Thanks to Justin Jaffray for explaining unification to me at the beginning of this project, and Jeremy Archer and Justin Manley for looking at early demos of the work!

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK