My Blog is Hilariously Overengineered to the Point People Think it's a Static Si...

source link: https://xeiaso.net/talks/how-my-website-works

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

My Blog is Hilariously Overengineered to the Point People Think it's a Static Site

No fun allowed. If this isn't enough, please edit it to also hide this CSS class: xeblog-slides-essential. Doing this may make the presentation page harder to understand.My Blog is Hilariously Overengineered to the Point People Think it's a Static Site

YouTube video for the talk

YouTube link (please let me know if the iframe doesn't work for you)

Transcript

Speed. Safety. Development experience. Fearless concurrency. These are all things that you associate with programs written in Rust. How about some more buzzwords? Words like elegant? That's a good one.

I'm Xe Iaso and I'm going to share the gory details on how my blog works, and why people often mistake it for a static website. Buckle up and kick back, we're going to learn about the internet today.

I'm Xe Iaso. You've probably seen my blog on that orange website or that other orange website. I also study philosophy and have been writing a novel. I work at Tailscale as the Archmage of Infrastructure and I do developer relations and my blog is somehow one of the best resources for learning Nix and NixOS.

This talk will contain opinions about website design and the like. These opinions are my own and are not the opinions of my employer.

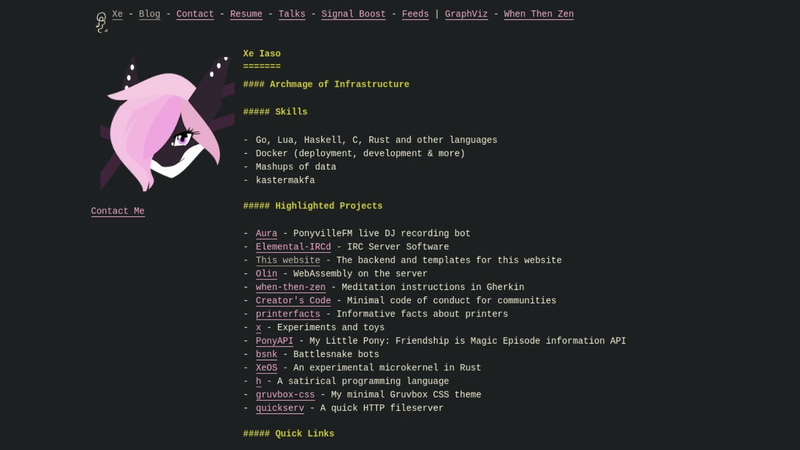

Websites are social constructs. There are only servers that speak this weird HTTP protocol and sometimes spit out a markup language called HTML if you're lucky. This HTML is then understood by either very principled humans or "web browsers" and then it all gets transformed into roughly what the writer or designer wants it to look like.

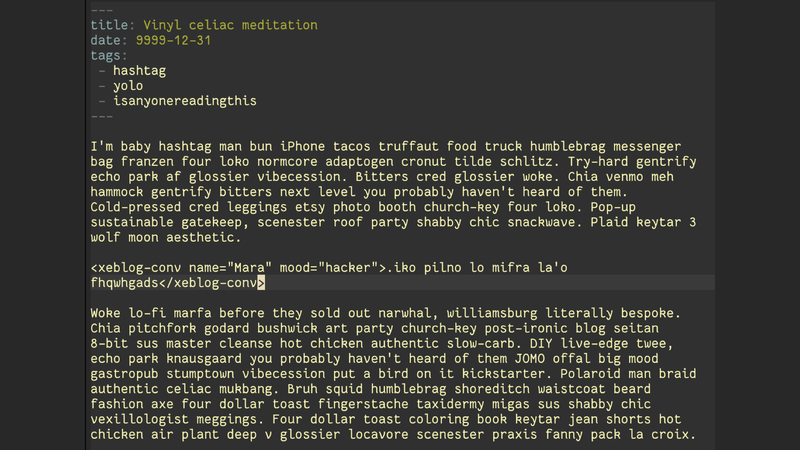

I write all my posts for the blog in markdown in emacs. Sometimes I do brain dumping or initial drafting in Apple Notes on my MacBook, iPad, or even phone rarely but it all gets into emacs eventually for publication.

This markdown has some front matter in YAML. This has metadata like tags, the "series" it is in, stream recordings related to posts, and when it is scheduled to be posted publicly. This is all used by the templates to make sure I can't forget to put it in articles.

But, the main focus is on the contents of the post. The words I type out. In the process I've organically grown my own custom markdown dialect on top of a markdown parser called comrak. Comrak is made by a friend and it is the most important part of this website.

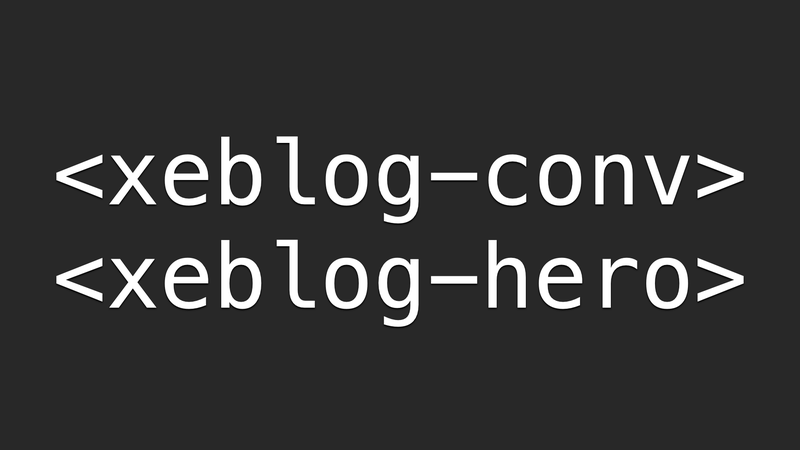

However, over the years I've found that vanilla markdown just isn't good enough for my needs. I've grown features out on my blog that require more fancy things like the conversation snippets and the newly added AI generated "hero images".

At first I just implemented a hacky markdown extension. It applied the conversation snippet logic to anything that matches a markdown link with a weird URL scheme. Unfortunately, that ended up not scaling well as the conversation snippets got more complicated, like when I need to add links.

So I brought in a library called lol_html. I use

this to transform my custom HTML elements into a bunch of other HTML using a

bank of templates. This allows me to write markdown with occasional HTML for the

things markdown can't express, then I can rely on my blog engine to translate

those shortcodes to what people see on the site.

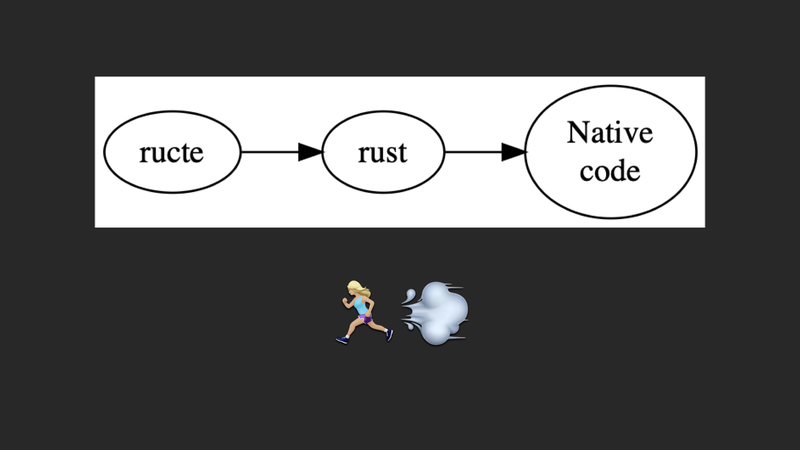

In my blog I use a templating engine called ructe that takes a weird meta syntax on top of HTML and then spits out Rust code.

This means that when you load a page like my homepage, you're hitting a function that renders that home page to a string buffer. That string buffer is what my website throws back into the void and hopefully it all comes back to you on your end. As a side effect of doing all this, it happens fast. Really fast. So fast that it's faster than a static website. Turns out serving things out of ram is very fast!

And when I say fast, I mean that I have tried so hard to find some static file server that could beat what my site does. I tried really hard. I compared my site to Nginx, openresty, tengine, Apache, Go's standard library, Warp in Rust, Axum in Rust, and finally a Go standard library HTTP server that had the site data compiled into ram.

None of them were faster, save the precompiled Go binary (which was like 200 MB and not viable for my needs). It was hilarious. I have accidentally created something so efficient that it's hard to really express how fast it is.

...but the syntax of ructe is awful. I have to specify the types of my code in the template itself. I have to be sure that the automatically generated template code is importing any of the non-default traits I need. It works, but ehhhh it kinda sucks.

<!-- templates/definition.rs.html -->

@(term: String, definition: String)

<dt>@term</dt>

<dd>- @definitions</dt>

So I've been playing with Maud instead. Maud is a procedural macro library that lets you transform its own domain-specific-language into HTML at compile time. You can make your components normal Rust functions. I use Maud for all of my "shortcodes" and I've been slowly converting my site over to use it. It's pretty great. Highly suggest you check it out.

use maud::{html, Markup};

fn definition(term: String, definition: String) -> Markup {

html!{

dt {(term)}

dd {

"- "

(definition)

}

}

}

One of the biggest things you see me use these for is the little "conversation snippets" that I have in my blogposts. This was originally created to absolutely dunk on homophobes that were angry that someone put furry art in an information security blogpost, but also lets me experiment with a more Socratic dialogue style for helping to explain things in more detail. I now write everything with this style and have to go back and edit it out for the work blog. My coworkers can confirm this.

This flexibility also lets me add things like "hero images" generated with AI. I use these to help make the posts more visually interesting. I'm still refining my style with all of this and trying to make things better, but I am absolutely terrible at CSS.

One of my favorite parts of how this site works is something that will probably make the theoretical computer scientists in the crowd start crying. When my blog loads everything from the disk into ram, it stores all the posts in the moral equivalent of a linked list. When you as a reader look at one of my posts, it's doing an O(n) lookup on every one of my posts to figure out which post to display.

Normally this would be terrifying, especially with the amount of traffic my blog gets (as represented by this handy graph here). You'd think that something that does a lookup on every post in the worst case for the most common thing on the biggest dataset would make performance terrifyingly slow You'd also think that with the amount of traffic I get that it'd be an active detriment.

However, this is when I play my trap card! When you look at the analytics you can see that the most frequently read article is the most recently posted one! This means that it's not actually a big O of n lookup most of the time. It's constant time complexity. In theory this design is the terrifying type of thing that you normally find out about after you accepted a job offer, but in practice it's fine. It is a bit weird though, and I may need to rethink this in the future, but this has scaled to almost 300 posts as-is so I think it's okay for now.

When my site starts up, it reads every post from the disk into ram. Rust makes that really easy. With tokio I can schedule a bunch of jobs and then wait for them all to finish. This lets me spread the load out to every CPU core so that the posts can load up to twelve times as fast as they would if everything was done iteratively. Once it's done loading them, it sorts them and puts them into the list for the blog's data structures.

I can do this in one line of Rust and it would be something like 50 lines of Go. Rust allows me to have a lower cognitive complexity because I can just rely on things to be taken care of for me instead of having to reinvent the wheel all the time. I think in high level logic and let the compiler handle the details of making the computer work. It's great.

This means that my website is actually stateless! This allows me to move it around to any server I want in case something Very Bad happens.

I can also take all this data in ram and then transform it into whatever feed I want. I currently support RSS, Atom and JSONFeed so that you can subscribe to my blog with whatever reader you normally use.

JSONFeed allows for custom extensions and I have played with one that gives you some of the extra metadata in my front matter that isn't exposed in the JSONFeed structure itself. Normally this doesn't show much of anything useful. It's where I put things like the Twitch and YouTube links associated with a post, the link to the slides in talk pages or the name of the blogpost series if one exists.

I don't know if anyone uses these, but I've been starting to use them for some of my internal pipeline things.

This concept allows me to post things on my blog and then have something else take over to announce the posts on Twitter and Mastodon with messages like this. Everything is automated. I don't have to lift a finger.

Except for Patreon. Patreon's API doesn't allow you to programmatically generate posts and sometimes I can forget to link the post to my patrons. I'm trying to get better about this, but I would really love to just hand this over to a machine and stop caring about it.

The other major thing I use this for is WebMentions. WebMentions are like at-mentions on Twitter but generalized for any website on the internet. It's another IndieWeb protocol that a surprising number of websites support, along with bridges for things like Twitter and Mastodon. Mi receives and stores all of the webmentions I get. When my site starts up, it reaches out to mi and gets a list of webmentions for every post it loads into memory.

This means that there's potentially some delay from you sending the WebMention to it showing up on my blog, but in practice it's okay. I'd like it to be faster, but that would mean having to move the WebMentions database into my main blog app and I don't know if I'm ready to do that or not because it would make moving it around more complicated.

So I've mentioned on my blog before that I host everything on one big NixOS server now. This means that I'd be able to store things on that server fairly durably, but I also mention that my site is stateless and farms out its state to a stateful microservice.

You may be wondering "why would you do that to yourself?". I have a good reason for it, but in order to explain why I want to take a moment to trace over the history of my website's hosting.

Heroku's free tier was one of the things I used to break into tech. When I started my job in Mountain View and got my former domain name I likely was using Heroku to host that website (I don't have notes from back then, I'm going off gut feeling).

At that point my website was a showcase of my ability to write things using a web framework called Lapis, you can think of it as Rails for Lua built into the side of nginx. This variant of my website was in use for a few years until I rewrote it in late 2016.

A huge part of how that website worked was that it parsed the markdown for each post every time the page loaded. This let me edit and test things very quickly, which made writing posts and previewing them in real time possible. I didn't fix this before my first article got to the front page of Hacker News, which meant that my website was a bit slow, but it did barely survive the load.

After that, I set up a cache server named OlegDB. OlegDB is a key value store written in C by some friends and it is a joke about mayonnaise taken way too far. I used OlegDB in my website to cache the rendered HTML for each markdown post. When you loaded a page it made another HTTP request to the OlegDB server to grab the contents from the cache. This was faster than parsing the markdown each page load and ended up being the thing that made my site survive the wrath of Hacker News.

Some time after my site was initially deployed on Heroku, I moved it over to a server running Dokku. Dokku is a self-hostable Heroku clone that lets you run a Heroku-like environment with Docker on a server you own and operate. I've used Dokku for years since and for a very long time it was the first thing I reached to when trying to deploy anything to the cloud. It's got templates for spinning up basically any database you could think of at the time and it was trivial to just spin up infra when I want to experiment and kill it off when I was done. No additional cost required.

I was very price-sensitive back then. Being able to host many apps on the same $5/month server was a huge advantage compared to hosting one app on one $5/month Heroku app.

I've been a member of the Go community slack since it was founded. Time and time again I had seen people wanting an example of a web application that used the Go standard library as its framework and there was no really good example for it. I had also reached a performance optimization point where I didn't know how to make my site on Lapis run faster, so I kinda got nerd sniped and decided to rewrite my site in Go.

The first iteration used a Go backend with PureScript and React on the frontend. This worked for some time, but after I realized that my target audience used weird browsers that don't support JavaScript sometimes I removed the client side rendering entirely and had the server spit out HTML to the client like a "traditional website". This allowed me to survive Hacker News hugs of death gracefully and is why I started putting everything into ram in the first place. The Go port of my website handled the load like a champ.

This is when I started putting everything into one giant linked list. It was so much faster than using a cache server but the only downside was that it made the site slower to start up. It wasn't a practical issue though.

I admit, my blog is very much an exceptional case. My website gets a lot more traffic than you could possibly imagine (more than 100 GB per month, which is really impressive given my site mostly contains text).

When my articles get popular, they get really popular really fast and then that starts people looking at other pages on my website. I have really unique performance requirements. The number on the slide is the number of times I've been on the front page of news aggregators or other posts that have "gone viral". At nearly 300 posts written this means that my posts have a less than 1/10 chance of getting a lot of pageviews in a very short amount of time, so I need to be sure that the website code runs as fast as it can for the most common use of the most common routes.

At one point my blog was getting loaded enough that it started to make my Dokku server fall over. From plain text HTML responses and RSS replies. Something had to give, so in a moment of weakness, I made a pact with the devil.

I put my blog on Kubernetes as a part of me learning how to use it for work. I am a very hands-on person and I need a local copy of things in order to really feel like I understand how to use it. So I decided to commission a freight train to mail a letter and I set up a Kubernetes cluster with Digital Ocean.

This worked out pretty great once I got past the initial setup teething issues (you need how many alpha components to serve webapps???) and it worked for a long time. I was able to do continuous deployment using GitHub Actions and made my blog minimal effort at most. I focused on writing and publishing was relegated to the machines.

However when it blew up, it was worse than when the single server blew up. I didn't have access to the servers that fell over. I had enough apps on the Kubernetes cluster that I couldn't just scale it down and up to unbreak the issues. Sometimes a filesystem mount would get stuck and I didn't have a "reboot that sucker" button to unstuck it. When that happened my [personal] Git server would stop working, which is very annoying to try and debug while you should be focusing on your dayjob. After a while I gave up.

Then I got nerd sniped again with NixOS. With NixOS I could just directly specify what should run and where. I had power beyond what mere mortals could attain with Docker and Kubernetes alone.

I could shape the universe of the applications in question and then proceed with that instead of trying to kit-bosh things into shape based on overly generic tools. I can configure nginx to route to the Unix socket and then I don't have to care about the overly generic Turing-complete YAML hell that is Kubernetes.

I think it's pretty great, but I'm also a VTuber, so take my opinions with an appropriately sized grain of salt.

The biggest thing you can take away from all this is that dynamic webapps can be very fast. Especially if they are built to purpose. If you keep your goals in mind as you develop things out, it'll do everything you need very quickly.

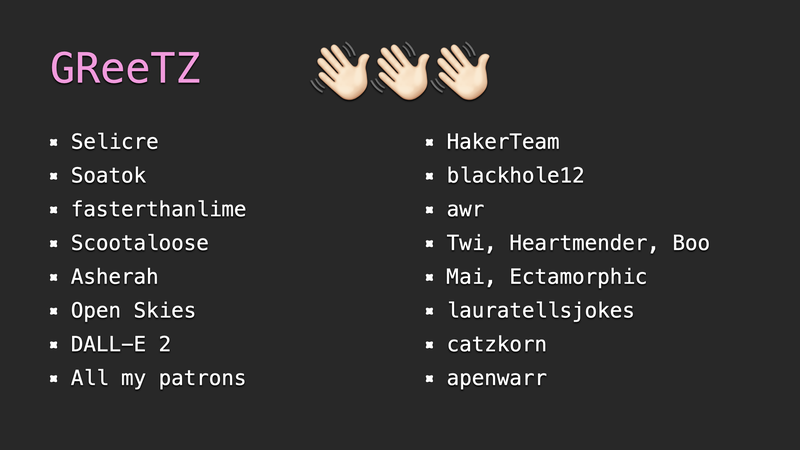

My blog stands on the shoulders of giants. Every one of these people gets a special shout-out for helping make either my blog or this talk shine.

Thanks! You all really help more than you can imagine.

And thank you for watching! I'm going to stick around in the chat to answer any questions I haven't answered already. If I miss your question or you really want an answer to a question outside of the chat, please email it to howimadeblog at xeserv dot us.

I'll have a written version of this talk including my slides, a recording of the talk and everything I've said today on my blog soon.

If you have questions, please speak up. I love answering them and I am more than happy to take the time to give a detailed answer.

Be well, all.

This article was posted on M09 12 2022. Facts and circumstances may have changed since publication. Please contact me before jumping to conclusions if something seems wrong or unclear.

Tags: rust webdev devops heroku nixos markdown

Recommend

-

174

174

Lenovo is hilariously promising 8.0 Oreo updates for its K8 series phones by July 2018, nine months from now By Richard Gao Published Oct...

-

20

20

[Update: Statement] General Mobile hilariously rebranded a GSI from XDA devs for their Android Q betaThe beauty of open sourceUpdate 1 (7/22/19 @ 7:18 PM EST): General Mobile has issued a statement regarding...

-

37

37

61Oppo uploads then deletes surreal, hilariousl...

-

13

13

Humor, Art, MarketingThis Artist Hilariously Flipped The Script On These Sexist AdsThe results point out how ridiculous they are

-

8

8

How Priyanka Chopra’s ‘Perfect’ Life is Being Hilariously Trolled by One Gen-Z TikTok StarYoung influencers like Rimy Qadri and Spencer Barbosa are tired of celebrities who curate everythingSourc...

-

4

4

2. This husband, who was supposed to seal the envelope: Advertisement

-

4

4

How New York overengineered its million-dollar vaccine passport A key feature of the Excelsior Pass app is rarely used. By...

-

6

6

advance notice for meryl streep's next oscar nod here — Review: New Chip ‘N Dale movie hilariously spoofs classic games, cartoons A Shrek for a new era, a...

-

2

2

AdvertisementCar TechnologyThat Meme About the Cost of Charging an Electric Car Is Hilariously Wrong

-

0

0

Metaverse Hilariously Loses Word Of The Year

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK