Why are there so few economies of scale in construction? Part I

source link: https://constructionphysics.substack.com/p/why-are-there-so-few-economies-of

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Why are there so few economies of scale in construction? Part I

(Note: trying an experiment where I write somewhat shorter posts somewhat more frequently. Any feedback is welcome.)

Producing goods and services is typically subject to economies of scale - as the volume of output rises, the unit cost of each thing being produced falls. Economies of scale are common - we don’t find it surprising when a large company like Walmart or Amazon or Borders (rip) can drive a smaller “mom and pop” competitor out of business with low prices that the competitor can’t match, and we’d expect that a giant company like Toyota can produce cars much more cheaply than a small boutique manufacturer like Aston Martin.

Economies of scale are common in manufacturing, in agriculture, in transportation, and in process industries. But they seem to be very uncommon in construction.

For one, we see few economies of scale at the level of individual buildings - a large building is only marginally less expensive on a per-square foot basis than a small building is. For instance, the construction estimating guide RS Means provides adjustment factors for building cost based on how much larger or smaller a building is than “typical”. Making a building seven times as large only drops the cost per square foot by just under 20%:

And Erkison 2021, using RS Means data, finds a very shallow cost-per-square-foot reduction as building floor area increases:

Likewise, when we looked at construction costs across different cities, the construction cost per square foot for single family homes in the US was only slightly higher than for low-rise apartment buildings, which use similar construction technology (light framed wood) but are 10x to 100x larger [0]:

And of course, the very concept of “cost per square foot” suggests a cost function that is largely independent of overall building size.

Similarly, we see few apparent economies of scale in production methods. Large volume builders use substantially the same methods of construction that small volume builders do, and do not in general produce buildings more cheaply. For instance, this new retirement community is built by a small regional homebuilder (Paran Homes), and the homes are priced at roughly $220 per square foot. Right down the street is another new retirement community built by Pulte Homes, the third largest homebuilder in the US that builds more than 20,000 homes per year, and the homes are priced at approximately $230 per square foot.

DR Horton, the largest homebuilder in the US, specifically mentions economies of scale in their annual report, but make no mention of production methods (instead they emphasize economies granted by market power):

We believe that our national, regional and local scale of operations provides us with benefits that may not be available to the same degree to some other smaller homebuilders, such as:

-Greater access to and lower cost of capital, due to our balance sheet strength and our lending and capital markets relationships;

-Volume discounts and rebates from national, regional and local materials suppliers and lower labor rates from certain subcontractors

-Enhanced leverage of our general and administrative activities, which allows us flexibility to adjust to changes in market conditions and compete effectively across our markets.

DR Horton, like most homebuilders, mostly subcontracts out the actual homebuilding to regional builders - cost control is achieved via competitive bidding, not by taking advantage of any type of high-volume production method:

Substantially all of our land development and home construction work is performed by subcontractors. Subcontractors typically are selected after a competitive bidding process and are retained for a specific subdivision or series of house plans pursuant to a contract that obligates the subcontractor to complete the scope of work at an agreed upon price

…We control construction costs by designing our homes efficiently and by obtaining competitive bids for construction materials and labor. We also competitively bid and negotiate pricing from our subcontractors and suppliers based on the volume of services and products we purchase on a local, regional and national basis.

Lennar Homes (the second largest homebuilder in the US), similarly states that they subcontract all their actual construction, and that “we generally do not own heavy construction equipment.” Homes built by Lennar and other large builders use largely the same systems, put together in largely the same way, that smaller builders use.

We also see the lack of economies of scale reflected in firm size - construction companies are much smaller than we might expect, given the size of the industry. To return to homebuilding, for instance, the largest US homebuilder (DR Horton) built 81,965 homes in 2021, 8.4% of the 970,000 total single-family homes built in the US that year [1]. The top 4 homebuilders (DR Horton, Lennar, Pulte, and NVR) accounted for 20% of the single-family home market in 2021, compared to over 54% of the US market for the top 4 car manufacturers, and 75% of the market for the top 4 industrial robot manufacturers. As of 2017 there were an estimated 66,000 homebuilding firms in the US.

If we look at real estate developers, we see even more fragmentation. The largest US multifamily developers, for instance, build fewer than 10,000 units a year, or just over 2% of the 370,000+ multifamily units built in a year in the US.

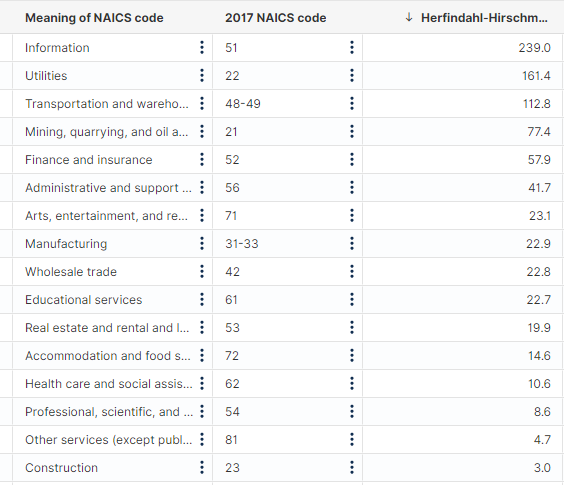

The same is true if we look at the construction industry more broadly - the US construction sector, for instance, has lower concentration than any other sector. The largest homebuilders have a market cap in the range of $25 billion, and the largest commercial construction companies have substantially lower valuations, compared to the $100B+ company valuations in most other sectors. By market cap, the largest US construction company is smaller than the 15th largest mining company, and the 20th largest car company, despite the fact that the construction industry is larger than the car industry and the mining industry combined.

So the question is, why do we see so few economies of scale in construction? This series of posts will try to answer this question.

[0] - Average new single family home size is 2500 square feet. A low-rise apartment building will vary, but a typical garden apartment will be in the neighborhood of 20,000 square feet, and a large 5-over-2 might be 250,000 square feet.

[1] - This increases somewhat if you restrict the denominator to “new single family home sales”, which excludes owner and contractor-built homes, as well as homes built for rent. By this metric DR Horton is over 10% of the market.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK