Everything is Broken

source link: https://www.notboring.co/p/everything-is-broken

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Everything is Broken

Kevin Miao explains a very real crypto use case: fixing the $14T securitization market

Welcome to the 1,483 newly Not Boring people who have joined us since last Monday! If you haven’t subscribed, join 143,885 smart, curious folks by subscribing here:

Today’s Not Boring is brought to you by… Stacker

Stacker is one of Not Boring’s longest-standing sponsors. They are a game changer for companies that want to scale beyond paid acquisition channels.

They’ve worked with 100+ brands — including Angi, GoHenry, Experian, Vivid Seats, Sidecar Health, and Extra Space Storage — to accelerate their organic and earned media strategies.

How it works: Stacker Studio produces newsworthy content for brands and then distributes the stories through their proprietary newswire to hundreds of news outlets, including SFGate, Chicago Tribune, MSN, Houston Chronicle, and 3,000+ other newsrooms.

The results? Hundreds of high quality/SEO-friendly pickups and invaluable brand awareness and authority.

If SEO is on your roadmap, Stacker is a no-brainer. Campaigns start at $6-8k/month, but they guarantee a minimum of 50 high authority pickups for each story and average 150-200 pickups per campaign! That means higher site authority, better search rankings, and the improvement in organic traffic you’ve been looking for. As a Not Boring reader, you get 20% off your first story.

Hi friends ,

Happy Monday! Past Packy here (I wrote this before I took off).

A couple of months ago, I got myself in a bit of internet trouble when I suggested on Cartoon Avatars that one of the use cases for crypto might be bringing mortgages on-chain. Since then, one of the questions I’ve asked myself is what the problem with my answer was:

Is it impossible to improve real-world financial markets by bringing real-world assets (RWA) on-chain?

Or am I an idiot?

I’m happy to report that it’s the latter: I’m an idiot. After the podcast dropped, my friend Kevin Miao reached out to say that he was actually working on investing in non-crypto credit assets and securitizing them on-chain. Kevin, unlike me, knows what he’s talking about in this area. He spent seven years in TradFi credit at Citi, where he was most recently running a structured credit trading desk, before leaving to run operations at Capchase with a focus on risk, underwriting, and portfolio management. After leaving Capchase, he matriculated at Harvard Business School before dropping out to go full-time on crypto as Head of Credit at BlockTower.

A couple weeks ago, we hopped on a call to discuss what he was up to. He began by illuminating how credit securitization impacts our daily lives - buying houses, cars, even cell phones - and launched into an impassioned and detailed 30-minute summary of why lending across trillions of dollars worth of assets was inefficient. The inability to tolerate this inefficiency, along with the clear business case for modernizing our financial infrastructure, informed his life’s mission of removing wasteful basis points from the loans and securitizations that make the economy go ‘round.

Originally a crypto skeptic, Kevin became convinced that blockchains offered a credibly neutral way for lenders to work together more directly and efficiently, and decided to dive in. Over the course of our call, what struck me was that Kevin wasn’t speaking in ideological language at all. He was talking about very specific and unsexy ways that bringing RWA lending on-chain could bring down borrowing costs and increase velocity. At the end of the call, I asked him, “Could you just write down everything that you just told me for Not Boring?”

Luckily, he agreed. This post is a deep and technical dive into why bringing RWA lending on-chain is an improvement over the current model. If Kevin is right, this is an enormous unlock and one that will expand crypto’s opportunity and impact.

My exchange with Kevin is a proof of Cunningham’s Law: The best way to get the right answer on the Internet is not to ask a question; it's to post the wrong answer. By being an idiot online, I was able to get to someone who actually knows what they’re talking about. I hope you learn as much as I did, and I hope that some of the skeptics read this and engage productively.

The revolution doesn’t need to be sexy to be impactful. Removing wasteful bps is a big win.

Let’s get to it.

Everything is Broken

(Click the link to read the full thing online)

Welcome to the clown show

“Oh boy, another crypto guy. Here we go again!” Let me start with an overdue acknowledgement to the haters.

From an outsider’s perspective, I understand why crypto seems like an absolute circus. Among the many mass delusions that the crypto community has hoisted upon itself over the last 12 months, my favorites include:

DeFi created $OHM, a financial perpetual motion machine, rendering millenia of economic teachings obsolete

People would be able to earn ever larger sums by simply walking or even sleeping

WAGMI because our shitcoins had inherent value (and certainly not because of an incestuous daisy chain of leverage)

The crazy thing is this truly does not even scratch the surface of the madness. @DrNickA offers a hilarious and cringeworthy recap here for those interested:

That said, despite being a skeptic of some recent crypto “innovation,” I was so compelled by the vision of a more efficient financial system that I dropped out of Harvard Business School to join BlockTower, a stalwart digital asset investment manager, in February. Founded in 2017 by Matthew Goetz and Ari Paul, BlockTower gave me a window into what was really happening beneath the surface of crypto.

And I have never had more conviction that I am in the right place, at the right time, and in the right industry.

To explain, I’ll frame the opportunity I see in the following way:

The goal: engineering cheaper cost of capital to borrowers

The problem: our anachronistic securitization infrastructure today sucks and extracts a tax on us all

The solution: the pursuit of efficiencies and new possibilities through blockchain

But first, some acknowledgements. Collaborators on this article include: Kevin Chan, Jack Carlisle, Anant Matai, the BlockTower Team, and Not Boring (of course).

The Case for Real-World Lending On-Chain

We know the future

One of my all-time favorite insights is the following from Jeff Bezos:

…'What's not going to change in the next 10 years?’… It's impossible to imagine a future 10 years from now where a customer comes up and says, 'Jeff I love Amazon; I just wish the prices were a little higher,' or 'I love Amazon; I just wish you'd deliver a little more slowly.' Impossible… When you have something that you know is true, even over the long term, you can afford to put a lot of energy into it.

To paraphrase, the man knows the damn future. Bezos knew that customers would continue to want lower prices, more selection, and faster delivery, and thus devoted tremendous energy to pursue those goals through Amazon. When the path forward is uncertain, it’s helpful to have a north star.

So, what do we, BlockTower’s credit geeks, know about the future? What are we certain will never change? To us, that’s easy.

Why do we know this? The core objective of every lender is to borrow money at X% and loan money at X+Y%, capturing a spread in the form of ongoing net interest margin (Y%) or through a one-time “gain on sale” of the underlying loan (roughly Y% * the effective duration of the loan). The cheaper the cost of borrowing (X%), the more profit you stand to make (until efficient markets drive down Y%). With that incentive, who would ever ask for a higher X%?

From the first modern clearinghouses in Liverpool, to the emergence of fractional reserve banking, to the proliferation of AI/ML in modern credit underwriting, driving down the cost of capital has long been the financial market’s north star. To this end, it’s hard to think of a more successful (or notorious) innovation than securitizations. Securitizations, archetypically mortgage-backed securities, are instruments which pool financial assets (loans) into tranches of debt that is subsequently purchased by investors.

Wait - what does the ‘Big Short’ have to do with this?

Securitizations are not sexy. You know that, I know that, and the people who asked me “so what do you do?” in Brooklyn circa 2017 certainly knew that. But, for better or for worse, securitizations have played a critical role in making the provision of credit more efficient. To understand how, let’s use the example of a typical mortgage-backed security (MBS).

Any mortgage-backed security can be thought of as a traditional company. Unlike traditional companies, however, where assets are factories, IP, or human capital; here, the “company’s” assets are mortgages, whose value derives from the contractual obligation of the underlying borrowers to make payments according to a fixed schedule. The company, in the form of a bankruptcy remote SPV, purchases these assets through a sale of liabilities to investors. These liabilities, or the tranches of the MBS, exhibit similar characteristics to any corporate capital structure: there are senior claims (tranches), junior tranches, equity claims (residuals), and so on.

Thus, a basic capital structure of a MBS could look like this:

What’s the point of all this financial engineering? At a high level, securitizations ratchet down the cost of credit through 3 main principles:

Law of Large Numbers

If you had to bet $1,000 dollars on coin flips, would you feel more comfortable betting $1,000 on one coin flip or $1 per coin flip repeated a thousand times? For risk-averse investors (i.e., debt investors), the latter is clearly preferred because one would expect the realized results to trend towards the true odds, or 50/50.

The same is true in lending. Even if I knew the probability that a loan would default, the idiosyncratic risks associated with a single loan are impossible to price. What if the borrower loses their job? What if an asteroid hit the town? Pooling these loans into a securitization dulls the impact of these exogenous, binary risks and increases an investor’s confidence that they will, in aggregate, perform according to the underwritten expectations. As a rule of thumb, the higher an investor’s degree of confidence in the outcome, the lower the returns one will demand.

Standardization (“Narrow Waist”)

If you want many, many things to be able to interoperate with many, many other things, there needs to be a narrow waist that is as constrained as possible between them.

-Alex Danco

Securitization is a form of standardization that enables very distinct forms of debt, ranging from 1-month credit card receivables to 30-year mortgages, to be purchased by and traded amongst investors. The “narrow waist” in securitizations is a 9-character identifier (CUSIP), a unit of ownership somewhat analogous to a unit of stock ownership in the equity markets.

Imagine if you could only trade shares of Tesla for other auto manufacturers; rational investors would require a greater discount to purchase that asset due to the relative illiquidity. Tranches of securitizations, standardized as CUSIPs (with consensus around cashflow waterfalls, legal structures, etc.), allow investors to trade very different forms of debt for each other, increasing the liquidity of their investments and lowering the rate of return they demand.

Product-Market Fit

People are different, and so are investors. Conservative investors, like banks or insurance companies, optimize for principal preservation. Others, like hedge funds, seek higher risk-adjusted returns. By creating senior and junior tranches, whereby higher-yielding junior tranches incur losses before lower-yielding senior tranches, you can cut up an asset into the distinct profiles that investors want. More competition, for both tranches, decreases investor leverage and often results in a lower aggregate cost of financing.

Pooling, standardizing, and tranching a pool of loans via securitization allows lenders to borrow at a lower-rate (X%). Say a lender has originated 100 $1 million loans, each yielding 10%. In securitized form, the senior debt may be a $70 million tranche yielding 4% and the junior debt a $30 million tranche yielding 15% (the standard target for hedge funds). As discussed above, investors are happy to pay this because they get a diversified pool of assets, with greater liquidity, and a better match for their preferences. But those pools of assets are now financed, by banks and hedge funds, at a weighted average cost-of-capital of 7.3%. This is the lower X%!

The question is, though, who gets the 2.7% (or Y%)? Part of this is fair compensation for lenders, but make no mistake: a significant portion of this spread is a symptom of our archaic securitization infrastructure and third-party fee extraction.

Too many hands in the cookie jar

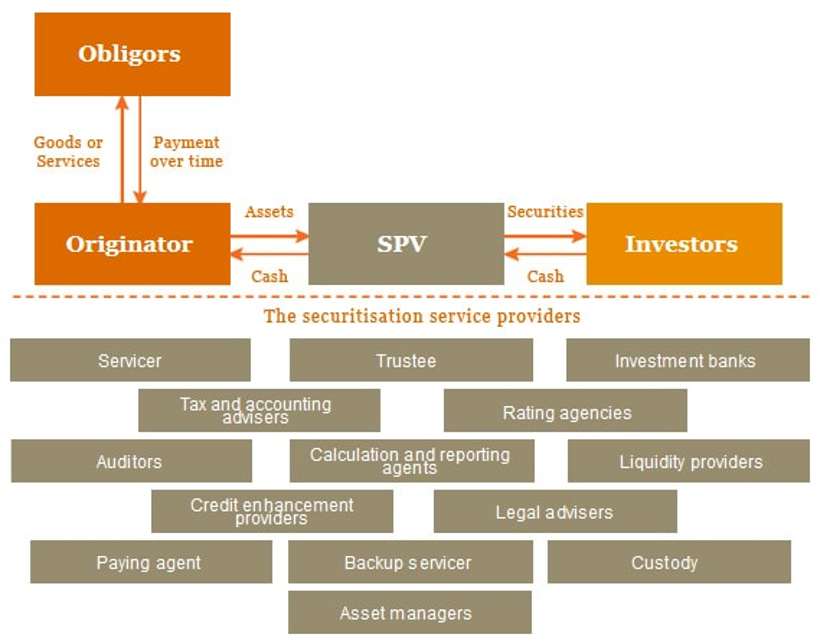

Our modern securitization infrastructure is held together by a patchwork of PDFs, Excel spreadsheets, and an absurd network of third parties that don’t need, or even want, to be involved. To give you a sense, PWC provides a great visual on the typical assortment of external parties and service providers in a typical securitization:

Orange boxes above the dotted line represent the key parties – obligors (the mortgage borrower), the originator (the lender that created the mortgage), and the investor (the buyer of the pooled mortgages). The core function of the securitization is to aggregate cash from the underlying obligors, divvy them up, and distribute the cash to investors.

Why do we need 14 service providers to do that? Let’s dig into the typical monthly flow of funds for a securitization:

Borrower pays: Mortgage borrowers send loan payments to an originator or servicer

Servicer remits the payment: Payments are sent to the securitization’s bank account

Custodial agents track loan performance: The custodial agent, which “owns” the loan (PDF loan documents) on behalf of the securitization, allocates each dollar to the underlying loan to document ongoing loan performance

Calculation agents determine payouts: The calculation agent calculates the principal and interest due to each tranche of the securitization

Paying agents pays: The paying agent debits the securitization’s bank account and wires the dollars due to each tranche to DTCC (a central clearing system that custodies most public U.S. securitization tranches on behalf of investors)

DTCC distributes the payments: The dollars are sent to custodial agents, which are often prime brokers

Prime brokers pays investors : Prime brokers remit the cash due to investors in each tranche, depending on their pro-rata ownership share

Auditors review everything: All transactions are documented by the reporting agent for auditors

Trustees aggregate a report: Trustees generate a monthly “trustee report,” which allow investors to track performance and verify payments were made correctly

Costs are accumulated each step of the way, adding an estimated 1% over the life of a securitization. This might seem small, but even a 0.50% interest rate reduction on a $500,000 mortgage saves $2,500 per year of post-tax salary, which is a meaningful difference in most people’s lives! That is a staggering cost for performing simple arithmetic, distributing cash according to a series of “if/then” statements, and providing an accurate report of transactions.

Assuming I haven’t lost you yet, here’s another example. What if I’m an investor and I want to buy a particular tranche of securitized debt? Today, the process looks something like this:

Instigation: I call up John, my favorite bond trader on Wall Street, and say “hey, I’m looking for this particular tranche and willing to pay $Z.”

Sourcing: John calls up a few hedge funds, but no one knows who owns the tranche I’m looking for. One ventures a guess that it’s Tim, over at Fund A. Luckily, John took Tim out to Lavo last week, so he gives him a call.

Getting an offer: After some posturing, Tim finally acknowledges he’s the owner. John asks him what price he’s willing to sell his bonds. Tim says “I’d sell for $Z.”

Negotiating the broker’s spread: “Just my luck” says John. There’s no money in it for him, buying and selling at $Z, so he tries to negotiate a spread for himself in the middle.

Final price: Ultimately, I decide I’m willing to pay no more than $Z and Tim (whose identity John has kept from me) would accept no less than $ZX. But whatever, right? There’s a buyer and a seller at price $Z, so there’s a trade to do.

F**k it: Wrong! John decides he’d rather wait for one of us to budge and refuses to broker the trade for no commission. Because Tim has only exposed his position to John, I have no way of completing a trade that *should* happen.

While this seems so obviously stupid, I know this is how it works because I was John in a past life. And while stupid can be harmless, I believe the compounding inefficiencies that plague our financial industry are more nefarious than they appear. In the second example, the inability to sell one’s position without going through an oligopoly of Wall Street brokers contributes to an “illiquidity premium” on this debt. That means that, all things equal, investors demand a higher yield on their mortgage-backed securities. This increases X%, or an originator’s cost of borrowing, which is transmitted to consumers in the form of higher mortgage rates.

It may be controversial to say that we’ve reached the theoretical limits of our existing system. But it’s not controversial to say that our existing system is like Windows XP; I’m pretty sure that a good portion of the “tech stack” on Wall Street is still a macro-enabled 1997 Excel Workbook. So what would a new operating system for securitized credit look like? One in which the core first principles - larger scale, more liquidity, and better targeting - were enhanced through new technologies and removing intermediaries?

Can you feel it? You know what’s coming, right? Wait for it…

Crypto fixes this…

When I was a mere peon in Citi’s securitization engine, I stumbled across a seminal 2017 paper titled Applying Blockchain in Securitizations. To the authors, this technology held transformative potential for the $14 trillion U.S. securitization market by:

Increasing efficiencies, disintermediating traditional parties, and lowering costs

Enabling more transparency and regulatory compliance

Improving data security, analytics, and privacy

Unlocking liquidity and new financial market solutions

What really caught my eye, however, were the authors themselves. This wasn’t a white paper written by some pie-in-the-sky prognosticators in a Discord, but a paper commissioned by the securitization industry itself! If the Structured Finance Industry Group (SFIG) saw the potential, I figured I should take it seriously. I volunteered for every internal blockchain initiative I could, including scoping out how blockchain technology could streamline Citi’s own securitization practice in 2019. But you know how it goes when attempting to disrupt yourself…it soon became clear that if someone was going to figure this out, it probably wasn’t someone within the shell of yesterday’s financial hegemons.

Fast forward to today and DeFi protocols like Centrifuge are already replicating the core function of a securitization - aggregating payments, dividing them up, distributing them to investors - by leveraging a public ledger, smart contracts, and stablecoins. Investors on Tinlake, Centrifuge’s marketplace, can purchase DROP and TIN tokens (NFTs that represent a senior or junior “on-chain CUSIP,” respectively) and receive ongoing distributions associated with their investment.

What’s the point? Contrast the traditional flow of funds, laid out above, with the flow of funds through Centrifuge:

Borrower pays: Same story - borrower makes their monthly payment to the servicer

Servicer remits the payment: US dollars are converted into a stablecoin (i.e., programmable money) for interaction with smart contracts, which are allocated to…

Loan-level NFTs: Payments are tracked against NFTs that represent each individual loan on the blockchain (as well as relevant characteristics like interest rate, maturity date, past performance history, etc.)

Automatic payment calculation and distribution: Smart contracts, whose “if/then” payment waterfalls are pre-programmed and auditable by all parties, automatically calculate and apply the payments directly to DROP/TIN holders

The astute may see the conspicuous absence of steps 8 and 9 (auditing and reporting), but I’m not trying to pull a fast one on you! With the loan-level and DROP/TIN transactions ledgered on a public blockchain, auditing and transparent investor reports are done by simply querying the data on a blockchain. Even cooler: unaffiliated companies, like EMBRIO.tech, are already building on-chain reporting technology specifically for Centrifuge’s securitizations.

It’s also worth noting that the emergence of these value-added services being built on top of Centrifuge is enabled by the foundation of a credibly neutral, open, and public blockchain. Just imagine if our new securitization operating system had the superpower of Apple or Android’s app store: the meritocratic, market driven dynamics of app-developers winning customers with superior products! Surely that’s better than the Wall Street oligopoly’s lack of incentive to innovate.

Couple all of this with the blockchain-native capability to identify who owns what asset, trade said asset without an intermediary (facilitated through the narrow waist of ERC-721 token standards), and you might even loosen John’s grip on the mortgage liquidity of the Eastern Seaboard. And while the ultimate savings of streamlining these processes may “only” amount to bps, at the scale of our $14 trillion securitization market, even a 25bps efficiency gain amounts to $35 billion a year back in borrower’s pockets.

Caveat: today, using a blockchain-enabled securitization engine still requires navigating a parallel traditional system (i.e., steps 1 and 2 are handled at least partly off-chain in the good old conventional style). As crypto-natives with deep credit and professional finance expertise, we may literally be the only ones on Earth that can do this right now (not great for the expanding liquidity argument). But our conviction that this will change comes from a number of places including 1) institutional-scale mortgage backed securities already using blockchain technology for servicing and 2) the ongoing innovation around crypto-wide on/off ramps, which can be repurposed (yay composability!) .

I get that shaving basis points off securitizations isn’t exactly the most exciting undertaking. And the reality is that a lot of what I covered above could be done without the blockchain (although I’d argue our existing network of siloed databases and non-modular technical architecture are nearly insurmountable hurdles). But as SFIG already pointed out, one of the core benefits of doing this on the blockchain include:

Unlocking liquidity and new financial market solutions

I am personally sympathetic to the view that applications on the blockchain can’t simply do things better than they’re done today; they need novel applications to compel entire ecosystems and industries to pay the immense switching costs associated with leaving the status quo. While predicting what will come out of this white space - use cases specifically enabled through the blockchain - is definitionally impossible, I can render a few possibilities:

Originators as creators: Today’s NFT creators often collect a royalty (1-10%) every time their NFT is traded in the secondary markets. In credit markets, the originator of a loan gets no such benefit; the spread is captured by John, the broker that facilitates transactions between investors. As lender profits are squeezed, originators could issue loans onto a blockchain-enabled system that offers a SaaS-like stream of recurring revenue via royalties on secondary market trades. In turn, this may reduce the upward pressure on rates they charge their borrowers.

Open credit scoring: Historical performance is the strongest indicator of future performance, which is why FICO scores (despite reports of its demise) generate billions of dollars in revenue for the credit bureaus. The bananas thing, though, is that our payment data is collected by the bureaus and sold back to lenders, who pass the cost back to us. Contrast this with a blockchain-enabled system, where the availability of (anonymized) on-chain payment histories could eliminate the bureau’s stranglehold over this goldmine of data. Even more exciting, perhaps you - instead of Experian - could own and monetize your own credit history.

Reduce gain-on-sale: Fannie Mae estimates that 6% of the total cost of U.S. homeownership is a result of lender gain-on-sale, which compensates lenders for the 1) time lag between origination and loan sale, 2) uncertainty of execution, and 3) embedded process inefficiencies. Originating loans on-chain, with smart contracts executing securitizations for de minimis additional cost, could materially reduce gain-on-sale while increasing lender profits by reducing the time-and-cost-to-securitize (freeing up expensive working capital).

Jurisdiction agnostic securitization: Even though I’ve been ragging on the existing U.S. securitization infrastructure, we are still orders of magnitude ahead of most other countries. In developing nations, the financial infrastructure to create, assess, operate, and generate investor interest in securitizations is basically non-existent. Could this borderless technology - by pooling assets, increasing liquidity, and enhancing investor product-market fit via blockchain-enabled securitizations - decrease the cost of credit to consumers in developing nations? All signs point to yes.

Obviously, we are still a long way away from this future; plenty of legal, technological, and behavioral hurdles remain. But at this point, I can only assume we know the limits of our existing system: securitization infrastructure has barely changed since the 1980s. So what do we have to lose by exploring a new path and the possibilities of this technology?

My rule of thumb: if something can be better, we ought to try and make it so.

Bear markets are for building

At this point, you’re probably wondering if I sincerely care this much about building a more efficient system for securitizations. What kind of freaking psychopath would! But let me assure you that I do and I’m not alone: building a better financial system is the core ethos of DeFi. As Frank Rotman has articulated, crypto is a movement of mass civil disobedience against existing systems that we know can, and should, be better. Yes, this industry is filled with grotesque and ostentatious bullshit, but closer inspection reveals countless individuals who are equally motivated to create a better future.

The question, then, is how to build it.

Personally, I don’t believe that crypto can engineer this new system purely through token incentives or marketing ploys. Instead, the pursuit of systemic change begins by deeply understanding how (and why) our existing systems work and solving little problems, for specific customers, on our path towards securitizing a new future. Put another way: in the words of Henry Ward, CEO and founder of Carta, we know “we want to build a car but…how do we provide utility along the way?”

For us, the “car” is a democratized, end-to-end system where technology-enabled securitizations create efficiencies and unlock new possibilities for us all. We are honest with ourselves about the obstacles and our odds, as an industry, of designing a new operating system for our global credit markets. We are definitively the underdogs. It will take a decade, or longer, to achieve.

We will expend an outrageous amount of our collective energy chasing after the north star: engineering an ever lower cost of capital.

But we know the future. And that’s energy well spent.

Thanks to Kevin and the BlockTower team for writing this piece, and to Dan for editing!

That’s all for today, we’ll see you Friday morning for a Weekly Dose of Optimism!

Thanks for reading,

Packy

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK