Why Are Christian Video Games So Bad?

source link: https://medium.com/@mediocratesgames/why-are-christian-video-games-so-bad-ec1ef47afa0b

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Why Are Christian Video Games So Bad?

Why Are Christian Video Games So Bad?

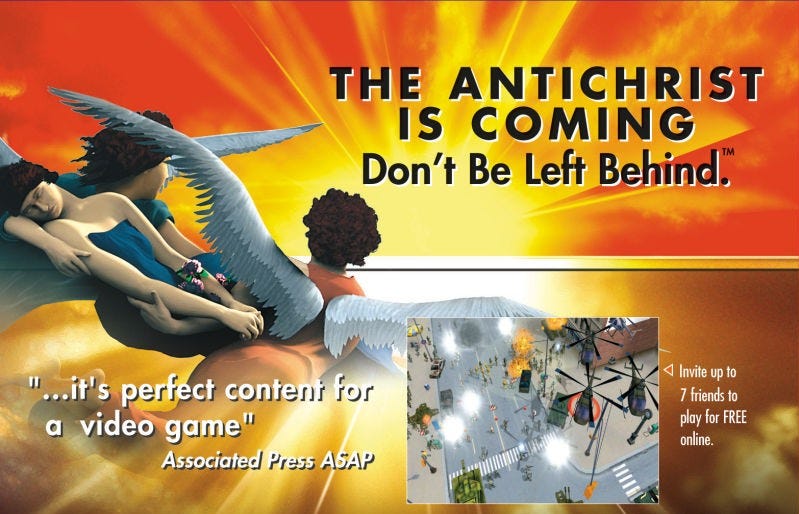

Perhaps naively, I had high hopes for 2007's Left Behind: Eternal Forces. The IP on which it’s based can best be described as Bible-spinoff-fanfiction turned into a best selling series of political thriller novels. They’re based on a particular interpretation of the book of Revelation and other end-times focused biblical texts. They even got spun out into a mediocre trilogy of movies featuring the one and only Kirk Cameron and later rebooted into one movie starring — wait, Nic Cage?

Being political thriller fluff, I assumed that the IP might at least translate well to an RTS, seeing as an evil world government & military are the major antagonist of the series.

I was wrong.

All the Christians (and children) have left the earth. Left Behind are the doubters, unbelievers, and anti-Christian government forces, and it’s up to you (Leonard) to convince people that the mass disappearance wasn’t because of an electromagnetic pulse, but God taking his faithful away from earth before plunging it into an apocalypse. And so you set off to find your friend Brad, using clunky RTS controls to convert folks to Christianity via a single click.

Perhaps the only use of the word “perfect” in connection with this game.

Wandering the abandoned streets of New York City, its building emblazoned with ads for EB Games, you encounter an unhinged street preacher who tells you to avoid the EVIL MUSICIANS. Surely, the game wants us to talk to the guitar-playing punks about Jesus and not run away from them.

Wrong.

The evil musicians are actually evil. The evil musicians will actually rip fat metal solos to convince you to their side.

You actually die if that happens.

Dedicated to finding your friend Brad, you restart the level. Another woman warns you not to go down a certain street because the local gang hangs out down there. Surely, the game’s creators want us to talk to the financial-district-street-inhabiting-street-thugs about Jesus, not scared of flesh-and-blood enemies. (By the way, the opening cutscene explicitly quotes the Bible to say that our struggle is not against flesh and blood enemies.)

The gang members will actually kill you. If you run away, they will follow you mercilessly until they can kill you.

You can’t pray for or convert these hoodlums.

Trust me, I tried.

The game’s entire message, from opening FMV to “tactical” unit movement, ends up being that Christians should be frightened of everything, no matter what verses they quote to the contrary. Be scared of the New World Order. Be scared of the UN, and all the non-Christian US presidents, and gang members, and teens with unnaturally colored hair who listen to metal, and basically anyone from New York City.

Left Behind is propaganda, top to bottom, that plays into the core fears and identity politics of rightwing Christian America. It wears its message on its sleeve, and its hat, and its sweater vest: the world is out to get us for being Christians. The fears that made the Left Behind books immensely popular on release in 1995 are eerily similar to those bandied about by talking heads on Twitter and Fox News nearly thirty years later.

Eternal Forces spends SO much time preaching its pseudo-gospel that no space was given to actually making the game good. Every character has a paragraph(s)-long background about how they did or didn’t come to faith in God. There are loading screens which play the Kirk Cameron/Ray Comfort evangelism hits about MACROEVOLUTION and Something-versus-nothing creation. There are worship songs put into the game and links to “talk about it” with someone (though they don’t work anymore in 2022).

But none of the space dedicated to preaching at the player makes the game any better. It is clunky, unintuitive, and ugly. There are, as far as I can see, about 6 character models in the game and only one song, not counting the CCM hits on loading screens. It is a flat, forgettable vehicle where only one thing matters: a gospel of fearful identity politics.

The actual video game? It never mattered.

Christian Didacticism

No funny joke on this caption. Play Adios! It’s really freaking good.

I started thinking a lot more deeply about Christian games when I came across Doc Burford’s excellent essay should art say things? Burford’s not just waxing poetic, either: he actually writes for great video games, like Hardspace Shipbreaker and Adios. Not coincidentally, Adios is one of the most moving games I’ve ever played, and stands as a shining example of just how powerful games can be. In the essay, he argues against the idea that art always has some hidden meaning or some philosophy it’s trying to instill in the audience.

“Art is so many more things than something so small and limited as commentary. Art is a rhythm, a smell, a taste. Sometimes art is that creeping sense of dread you feel in your heart when the bills are due. It’s heartbreak. It’s elation. Sometimes it’s a way of helping you cry. And that’s just the audience-facing stuff. Art, for the artists, is a release and therapy as well.”

Far too much Christian art fails here. It’s preaching, but with some set dressing; it’s a political soapbox evangelist wearing a costume. The arts allow us to express and to feel so deeply in ways that words alone could never. When Christians make movies about how being a good dad is like being a “good” cop or whatever, they’re not interested in those emotions too-deep-for-words. The movie is only a vehicle to get you in the door of some ideological church; the medium is fundamentally compromised in favor of the message, and so nothing resonates with the viewer unless they were there already.

Hemingway knew this, too. Referencing The Old Man and the Sea, he said that, “No good book has ever been written that has in it symbols arrived at beforehand and stuck in… I tried to make a real old man, a real boy, a real sea and a real fish and real sharks. But if I made them good and true enough they would mean many things. The hardest thing is to make something really true and sometimes truer than true.” Christian efforts at the arts have, for centuries, arrived first at meaning and symbols; and thus, nothing feels real.

Contemplation, Interpretation, & Liturgy

run? uh, no thanks, he looks BADASS

The Reformation radically redefined how Christians thought about art. Scholar & professor Daniel Siedell tracks this change in his book God in the Gallery.

“The role of art (and the aesthetic)… was changed, from a primary means of spiritual contemplation and communion to a supportive function as a tool of education and communication.”

Eventually, post-reformation liturgical art was almost always accompanied by some sort of interpretive, explanatory lens. Ambiguity and the subjective experience of the viewer were obstacles to avoid at all cost in a church setting that believed in a faith that was primarily preached- “the ‘I believe’ of ancient Christian faith was transformed into an ‘I believe that.’” In broader church history, Christian liturgical art was meant to communicate truths that mere verbal communication couldn’t. But belief, reduced to an acceptance or rejection of doctrinal statements, gives way to a weak sort of art: art that is primarily (if not solely) concerned with communicating explicit doctrines to the viewer and leaves no room for the experience of the work. This, in turn, renders the artwork itself pointless: if the truth it contains could merely be spoken aloud, why not simply preach it and be done? Christian art, concerned primarily with being didactic, is therefore useless.

lmao kirk, you absolute clown

Art that attempts to bait-and-switch the viewer into hearing the real truth carries no real weight of its own. It’s an ineffective sham, too: how many non-Christians do you know walked out of KIRK CAMERON SAVES CHRISTMAS wanting to worship Jesus? (That’s barely a hypothetical! I know the answer’s zero!) Art has to be more than a vehicle; it has to stand on its own; it has to contain something more than dogma repackaged & regurgitated.

I don’t want to drown you in Bible verses here, but I think a couple will be instrumental in getting to the heart of the flaw of Christian video games.

When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers,

the moon and the stars, which you have set in place,

What is man that you are mindful of him,

and the son of man that you care for him?

Psalm 8:3–4

David, in the eighth Psalm, was overwhelmed by the sheer majesty of the world around him, and in it was truth that he couldn’t have grasped by merely hearing it spoken. Again, in the nineteenth Psalm, he wrote that The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork. (Psalm 19:1) The Bible itself testifies to the fact that there is truth to be absorbed, not mere factoids to be memorized, by witnessing the beauty of the world. The Bible says what Christian video game developers have been missing for decades: there is truth- profound truth- that can be found only outside the confines of human language.

Random Bible Verses

Well I don’t remember Moses having to do THIS in Exodus

The Christian games I played lacked David’s divine imagination: the “game” parts of the games were chaff, discarded in favor of randomly and obtusely inserted Bible verses. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they almost always completely broke the flow of play: in The Bible Game, you could press Select to view a verse. (Weirdly, you’re only able to look at each verse once before it disappears from your inventory.) As far as I could tell, looking at those verses served no practical function in the game. In Exodus, between rounds of its Boulder Dash clone, you answered trivia questions about Moses’ life, and as a reward, you got, uh, extra Bibles? Ominous Horizons’ whole plot revolves around retrieving pieces of Gutenberg’s first Bible which has been ripped to pieces and spread over the earth by Satan? And you pick them up but they don’t serve a function outside of just being on the screen while you shoot sand dudes or whatever? And Gutenberg can’t just make a new one because he’s depressed?

Christian games are weird, man.

Gutenberg, my man, take a Zoloft and get back out there.

These games are overtly other kinds of games with Bible verses shoehorned in. If you strip them out, what’s left? Lackluster clones of better games. Ralph Bagley, CEO of N’Lightning and developer of Ominous Horizons, said “We’re going to hold the word of God up and illuminate the place. We’re taking the land back from Satan.” It’s revealing, but I don’t think Bagley meant it to be: they never wanted to make a new thing, or to build a new place. Ominous Horizons feels like bad-Quake with or without the Bible verse pickups, because its creators were chiefly concerned with putting the Bible in front of players. The devs never learned tight, speedy level design from Doom or weapon variety from Quake. The art of game design was discarded for the sake of the message. N’Lightning merely tried to hold the word of God up, inside of somebody else’s creation. They could never have made something new: they didn’t know how.

The Work Should Brighten The Minds

In 1135, Suger, abbot of St. Denis, began to lead reconstruction of the local church just north of Paris. He recorded their building efforts, and his thoughts on the project, in what was eventually collected into a book which serves as a counterargument to modern Christianity’s lowbrow didacticism. Abbot Suger’s verses were inscribed on the church’s doors in copper and encapsulate the way that art pivots the natural mind from the low & material to the high & sacred.

Whoever thou art, if thou seekest to extol the glory of these doors,

Marvel not at the gold and the expense but at the craftsmanship of the work.

Bright is the noble work; but, being nobly bright, the work

Should brighten the minds, so that they may travel, through the true lights,

To the True Light where Christ is the true door.

In what manner it be inherent in this world the golden door defines:

The dull mind rises to truth through that which is material

And, in seeing this light, is resurrected from its former submersion.

Abbot Suger refused to compromise on the medium of the art of architecture. The doors of the Basillica of St. Denis’ church didn’t overtly preach the biblical gospel, but the verses provide the lens through which viewers should view the magnificence of the building. The church wasn’t opulent for opulence’s sake; it was crafted in excellence because God was deserving of excellence. When attendants viewed its majesty, they should be reminded of the greater majesty of Jesus: the nobly bright work was a mere shadow of how much more noble and bright God was. In comparison to the goodness of God, the magnificent church was merely a shadow, but Suger’s hope was that it would cause the dull mind to rise to truth through that which is material.

On the other hand, when Christian art sinks to didacticism, it compromises on beauty & excellence. It doesn’t demand the finest architects and artisans, it hires the cheapest available workers to build its shoddy structures. In poor script, it graffitis its own message onto the face of its building, so that no one will mistake it: this building may welcome in the people who have already bought the message, but only by distracting from the structural flaws with the crudeness of its communication. Anyone else, though, can see its inevitable collapse. Why would anyone see God as worthy of worship if His own followers settled for mediocrity?

But, surely, there’s a video game out there- a real, Christian video game- that doesn’t fall so short. Right?

Enter The Sleeptime

i will erase every last trace of that bastard gumshoe gooper from our world if it kills me

You would be forgiven for not recognizing that Hypnospace Outlaw is, in fact, a Christian game. At first blush, it assaults your senses with bright, clashing colors, too-loud midi-music and robotic text-to-speech that hearkens back to an internet still in its infancy, full of mystery and hope for what the world could be. To be clear, this is not a faithful recreation of late-90s internet; in universe, Hypnospace is one of many “sleeptime” internets- ones you access via neurally-linked headband connected to your PC while you, well, sleep. And while that technology never existed in our world, it feels real & alive. To explore Hypnospace is to travel through memories that were never actually yours, or anybody’s.

The pages of The Cafe and Teentopia were made out of an affectionate nostalgia for 90s internet, but not a rose-colored one. Users’ homemade pages are broken; broken aesthetically, but also personally. Imperfection coats the Hypnospace experience: there are real humans behind these pages who make mistakes and try to present better versions of themselves. Reading their pages and interactions with one another reveals quiet hopes and insecurities. Edgelords and oId folks worried about communists may not engender much sympathy at first, but look closely enough, and you’ll see hints of the sadness and tragedy that haunt their waking hours.

But what makes Hypnospace Outlaw a Christian game? After all, it contains none of the dogmatism of the other games I mentioned. Jesus doesn’t come back to save the Hypnospace users. At no point does it stop and demand the player read through a gospel tract. By the measure of the other games in the video, Hypnospace Outlaw is an abject failure as Christian art, an indication of the developer’s own desire for worldliness and not Jesus. Or is it?

please let me kill gumshoe gooper please let me kill gumshoe gooper please let me kill gumshoe gooper

Hypnospace Outlaw is a Christian video game because it is a video game by a Christian. It is an effective one because, unlike games beholden to didacticism, it is good for the sake of being good. Jay Tholen, the developer, doesn’t make good art to bait-and-switch players into hearing a gospel presentation: he makes good art because he couldn’t do otherwise. God created the world, made it beautiful, and called it “good”; artists, because God is good, can imitate His creative acts. The sky itself proclaims God’s goodness by its beauty, not by skywriting Bible verses; Tholen imitates this act of creation by making a work that is beautiful & good all on its own (no preaching required).

God made the world, and made it perfectly. God designed everything, from the beauty of the natural environment to the pure joy of friendship. And though we have the Bible to testify to His desire to be in relationship with us- mankind- we are also surrounded every day by beauty and goodness which testifies in a way too deep for words to the beauty and goodness of God. Artists, then, can’t compromise on their creative imitation of God’s creative work: they can’t stop short to explain what could never be put to words in the first place.

Tragically, Reggie never actually uploaded any woodworking tips.

Hypnospace Outlaw is a richly detailed, believable work. Tholen’s Christian worldview is revealed by its fictional (and real-life) creators’ love of beauty. It bursts at the seams with color and sound. It’s revealed by the game’s earnestness, quality, and attention to detail. It’s revealed in its belief in its own characters: in their tragedy and misdeeds, but also their redemption and desire for forgiveness. Hypnospace is carefully, lovingly crafted; simultaneously realistic and beautiful. How could a Christian make anything else?

Christian art can, and must, rise above the mediocrity of crude didacticism. For art to be any good, artistic imagination has to be unshackled from art-as-education kind of thinking. Christians needn’t fear their audience might miss the point: our deepest-held philosophies will always break through into our creations, shaping and molding them into something we can believe in as well. That much is as evident in Hemingway as it is in the church at St. Denis as it is in Hypnospace Outlaw. That art can and does exceed itself has perhaps never been put better to words than by Van Gogh in a letter to his sister: “One can speak poetry just by arranging colours well, just as one can say comforting things in music.”

Let the art speak.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK