How to use OKRs toward product-market fit

source link: https://uxdesign.cc/how-to-use-okrs-toward-product-market-fit-e575f0b58c51

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

How to use OKRs toward product-market fit

And track progress with confidence

When starting with OKRs, I found great inspiration by looking at practical examples from other product teams. And there’s lots of excellent content out there (tip: check out Tim Herbig’s stuff). However, most existing OKR literature lacks practical examples for brand new product initiatives. With this article, I hope to change this.

It is not easy to define the OKRs toward product/market fit

Finding and bringing forward a new idea to product/market fit is, for many, the nirvana of product development. But, how can we leverage the power of OKRs toward this beautiful state? While it might be easy to define the O (objective), e.g., “to demonstrate product/market fit, things get trickier with the KRs (key results). It’s unclear how to define success and measure progress toward something as daunting.

First, let’s try to agree on what product/market fit means. There are a lot of different definitions flying around. My favorite is Marc Andreessen’s: “being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market.” The definition is simple, concise, and understandable. Yet, it doesn’t provide clear pointers to how we can track progress towards it.

Choosing the right OKR type might help gauge and prioritize the work, define the ambition level and formulate the key results. Next, we will therefore evaluate three types; committed -, learning -, and aspirational OKR.

Committed OKRs

By using committed OKRs, the team pledges to 100% completion of their key results. Indications of delays should be escalated to management immediately, so that they together can take measures to get back on track. There are two circumstances in which committed OKRs could be beneficial:

- Everything is clear — you can get predictable results with little or no risk.

- The context is complicated, but not complex — there are known unknowns, and it requires judgment to move forward.

These circumstances might apply if we know with a high degree of confidence that customers would value our solution, we can deliver it in time, and it will predictably drive the business results (read more about high-integrity commitments). In other words, these circumstances do not apply to the early days of product development — when we know the least.

Learning OKRs

Learning OKRs are best suited to definesuccess when the outcome is uncertain or undefined (Head and Panchadsaram). Studies have shown that learning goals are more effective than performance goals when it is unclear how to proceed (check out this summary). All of this sounds like we are on the right track. On the other hand, typical key results for learning OKRs are as follows:

- Conduct 10 interviews

- Understand the top five pain points.

- Produce a document analyzing users’ pain points.

It quickly becomes very activity-based, rather than focusing on meaningful outcomes. Even if executed perfectly, completing these activities does not necessarily bring you closer to achieving the objective. The point should be to show progress and results, not to show that you are busy. So, learning OKRs with activity-based key results might not be beneficial for our case.

Aspirational OKRs

“Aspirational OKRs are, by definition, beyond reach. Taking big risks and falling short is somewhat expected. But failure is celebrated as a valiant attempt to get closer to the finish line, rather than evidence of a team’s shortcomings.” — Lisa Shufro

Going for and demonstrating early signals of product/market fit is certainly stretching for something beyond reach. In that regard, it might look like our context best fits in the aspirational OKR bucket. But, we still need a tangible approach to start measuring progress and defining success. To get closer, we must dig deeper into what challenges we have to overcome.

Tracking progress with confidence

According to Marty Cagan, successful products are valuable, usable, feasible, and still viable from a business perspective. These four attributes have associated risk:

- Value risk: Do the customer want this?

- Usability: Can the users figure out how to use it?

- Feasibility: Can we make this?

- Viability: Can we generate more revenue than costs?

The risks exist because your idea is based on imperfect information and guesses. Regardless of how much you believe in your new product idea, it still consists of assumptions that pose varying degrees of risk to its success. Some, if proven wrong, will break your entire idea. The product team’s job is to de-risk the new product initiative to a level where one can comfortably decide whether to keep investing in it. The comfort level ties directly to the confidence level, which measures how much you believe in the evidence gathered (more on evidence shortly).

This is where I want to make a bold suggestion that we should phrase the key results using confidence levels. I know confidence levels are not objective, but a very subjective thing. And thereby, we are making a cardinal sin in the OKR space. “Either you meet a key result’s requirements or you don’t; there is no gray area, no room for doubt.” (Measure What Matters, John Doerr). Despite fully agreeing with this statement, I still plead that we can and possibly should disregard it in the pre-product phase. For most, being confident that, e.g., your customers want whatever you are about to make should be an outcome worth pursuing.

Further, when used correctly, confidence levels can indicate progress towards product/market fit. What we need is a way to operationalize and quantify the confidence level.

It is time to look at a practical and very simplified example.

The A-Team putting confidence to the test

Company X is a SaaS company selling directly to consumers. The company has been performing well for years, but the growth rate is declining. Additionally, there is a need for new means to achieve its product vision. Therefore, the firm starts new product initiatives to serve existing customers, acquire new ones, generate additional revenue, and get closer to its vision.

The A-Team, one of the product teams at Company X, has been challenged with an end-of-year objective to demonstrate product/market fit for a brand new product. However, the company doesn’t want to keep investing in an initiative, quarter after quarter, without any sign of progress. Thus, the quarterly objective is to demonstrate early product/market fit signals. After discussing the strategic fit and context, The A-Team starts defining what a successful quarter might look like.

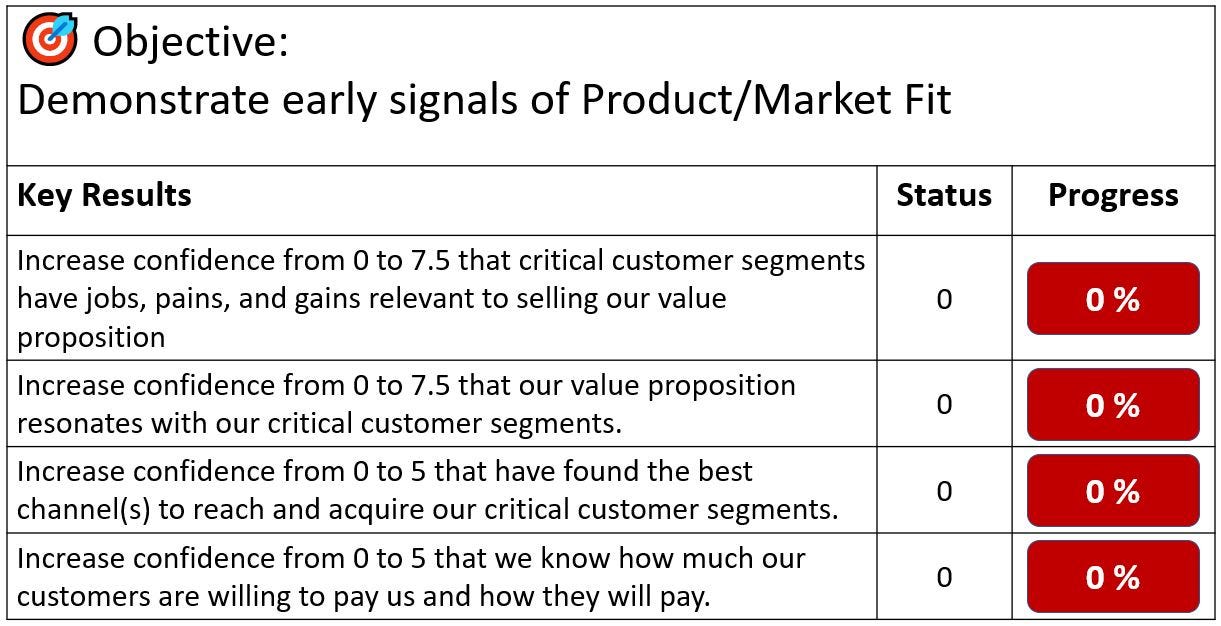

They assume that the main risks relate to whether the customer wants whatever they may make. Therefore, they want to reduce the desirability (another word for value) and viability risk. Using the Innovation project scorecard, they propose the following key results:

Key result proposals from The A-Team for the first quarter.

Management agrees to the ambition level, and the product team is off to work.

Because the A-Team already has a deep understanding of the customers and the market, they start generating ideas and hypotheses about what jobs customers like to get done in a better way. Then they de-risk the new ideas by conducting customer interviews, a lightweight experiment. The team determines the strength of the evidence using the following figure:

Evidence strength. The figure is inspired by Testing Business Ideas. Bonus tip: Read the book. It contains much content on evidence-based product development and has a library of useful experiments.

The evidence strength from the customer interviews is deemed weak (1/5), and the resulting confidence level does not move much. Nonetheless, it provides excellent qualitative insights and signals that the team might be on the right track with some tweaks. Having improved its understanding of the customers, The A-Team decides to test different value propositions with online ads. One of the ads outperforms the rest and passes all the pre-determined success criteria. Users clicking ads provides stronger evidence than what people say. Still, the level of commitment is minimal, and therefore the team deems it relatively weak (3/5). Seeing that there are now two different experiments indicating desirability, the team updates their key results as follows:

Key results after two rounds of experiments. Note that online ads may provide insights into whether the acquisition channel works.

And so the spiral continues. The team puts the idea through gradually more demanding tests, learning more from each step. After each test, the team determines the strength of evidence and the confidence level contribution. The insights also inform whether to abandon, change, or continue testing the idea. So, the process does not only provide a chance to validate the idea, but also to improve it.

“most great ideas are not born great (no eureka moment), they become good through the process of testing, learning and refinement/pivots.” Itamar Gilad.

At the end of the quarter, the status is as follows:

End of quarter status.

Overall, the results are pretty good. The team did not meet all metrics in full on time. But, that is not to be expected with an aspirational OKR like this. They did demonstrate early product/market fit signals. Further, they tracked progress, corrected the course when needed, and involved management along the way. So when it was time for the quarterly OKR check-in, the conversation did not contain any surprises. Everyone who came into the conversation was fully aware of what had happened, and they had also participated in determining the confidence levels based on gathered evidence.

Because of the progress made, management decided that The A-Team should continue its quest toward product/market fit in the next quarter. And then, the rest of the conversation focused on what was next.

Summary

Defining success and measuring progress toward product/market fit is challenging. There are many great examples of how to use OKRs when you already have a product, but there are few usable examples of how to leverage the power of OKRs in the pre-product/market fit area. With this article, I hope to have shown that using aspirational OKRs with key results metrics framed around confidence levels could be a good approach.

I’d love to hear your feedback.

Thank you for reading.

References and recommended reading

Testing Business Ideas by David Bland and Alexander Osterwalder

Evidence scores — the acid test of your ideas by Itamar Gilad

Product Management OKRs Resources Hub by Tim Herbig

The only thing that matters by Marc Andreessen

Coaching — Strategic Context by Marty Cagan

Discovery — Judgement by Marty Cagan

Measure What Matters by John Doerr

Building a Practically Useful Theory of Goal Setting and Task Motivation: A 35Year Odyssey by Locke and Latham (note that Teresa Torres refers to this research in her book: Continuous Discovery Habits)

Innovation Project Scorecard: Evidence Trumps Opinion by Tendayi Viki

Committed vs. Aspirational OKRs: What’s the difference? by Lisa Shufro

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK