How to stay optimistic in these dark times

source link: https://noahpinion.substack.com/p/how-to-stay-optimistic-in-these-dark?s=r

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

How to stay optimistic in these dark times

There are different kinds of optimism; let's think carefully about which we need.

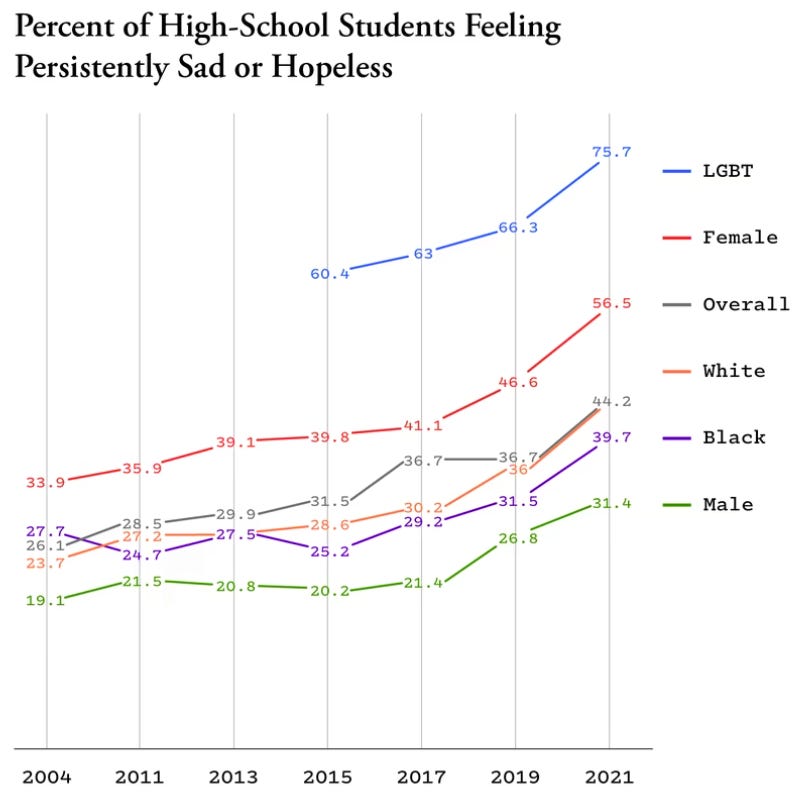

In 1979, President Jimmy Carter gave his famous “Crisis of Confidence” speech (also known as the “malaise” speech, though he didn’t actually use the word). Forty-three years later, it seems as if the country is stuck in at least as bad of a funk. In a recent article, Derek Thompson of the Atlantic reported on rising feelings of hopelessness among teens, and posted this startling graph:

Thompson’s colleague, Molly Jong-Fast, wrote a column around the same time describing how life now seems permeated with fear. And a January poll from NBC News found mounting dissatisfaction with the direction of the country:

Overwhelming majorities of Americans believe the country is headed in the wrong direction, that their household income is falling behind the cost of living, that political polarization will only continue and that there's a real threat to democracy and majority rule…[W]hen Americans were asked to describe where they believe America is today, the top answers were "downhill," "divisive," "negative," "struggling," "lost" and "bad."

While there might be long-term forces at work here — Thompson flags the rise of social media as a potential cause of teen unhappiness — it’s plain to see that recent world events give us plenty of reason to be upset. We are just now beginning to emerge (knock on wood!) from a pandemic that killed over a million Americans and forced many of us into social isolation. Our country has been in a state of social and political unrest for about eight years now, culminating in the protests and riots of 2020 and the coup attempt of 2021. Violent crime is at levels not seen since the 1990s. And now, spiraling inflation is outpacing wages, causing a majority of Americans to become poorer by the month. On top of all that, Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine brings back the looming specter of great-power war.

In other words, it’s a trying time to be alive in this world. I don’t fault anyone for being dejected, afraid, or angry. But at the same time, I think it’s important to stay optimistic.

There are certainly important reasons to be upbeat about the world. I’ve written about a number of these. They include (but are not limited to):

Ukraine’s valiant stand against the Russian invasion, assisted by the U.S. and by a suddenly more united and vigorous Europe

The steady progress of developing countries, especially in Southeast and South Asia

A possible acceleration of technological progress this decade

Improvements in the climate change outlook, thanks to green technology

But it’s obvious that the presence of these facts alone isn’t enough to generate a mood of optimism among the American populace. We need to view optimism as a deliberate strategy — a way of excising our malaise, not just so that we can live more fulfilling and happy lives, but so that we can make progress as a nation and a society. And while looking at the good news is surely part of that, there are a lot of other aspects to optimism besides simply saying “Buck up sailor, it’s not all bad!”.

So I’d like to think about what it means to be optimistic, and then think about how we can craft an intentional strategy for national (and personal) optimism.

Varieties of optimism

Optimism comes in a number of different flavors. One key distinction is how much you focus on your own actions and your own agency — whether you sit there and expect that things will get better, or whether you believe that you both can and must act to make them better. The philosopher Antonio Gramsci thought about this when he declared that he was “a pessimist because of intelligence, but an optimist because of will”. Here’s a quote from Gramsci:

You must realize that I am far from feeling beaten…it seems to me that… a man out to be deeply convinced that the source of his own moral force is in himself — his very energy and will, the iron coherence of ends and means — that he never falls into those vulgar, banal moods, pessimism and optimism. My own state of mind synthesises these two feelings and transcends them: my mind is pessimistic, but my will is optimistic. Whatever the situation, I imagine the worst that could happen in order to summon up all my reserves and will power to overcome every obstacle.

Optimism of the will isn’t necessarily about thinking that you yourself are going to be able to fix the world’s problems. It’s about the confidence and feeling of agency that comes from taking action. Yes, if you’re Volodymyr Zelensky, your decisions will have a big impact on the outcome of the Ukraine war. But if you’re a Ukrainian soldier fighting on the front likes against the Russian invasion, you know that your own antitank missile isn’t going to tip the balance of the war. Yet by shooting that tank anyway, you know that you’re simply being a spectator to the flow of history — not simply looking out the window and waiting for the world to happen to you.

Futurist Jason Crawford calls these “descriptive” vs. “prescriptive” optimism, while economist Paul Romer calls them “complacent” vs. “conditional” optimism. But it’s basically the same thing.

A second distinction is what kinds of things you’re optimistic about. The venture capitalist Peter Thiel distinguishes between what he calls “definite” and “indefinite” optimism — whether you think things will get better in general, or whether you have a specific idea:

You can expect the future to take a definite form or you can treat it as hazily uncertain. If you treat the future as something definite, it makes sense to understand it in advance and to work to shape it. But if you expect an indefinite future ruled by randomness, you’ll give up on trying to master it. … Process trumps substance: when people lack concrete plans to carry out, they use formal rules to assemble a portfolio of various options. … A definite view, by contrast, favors firm convictions.

Not everyone thinks this is a hard-and-fast distinction. My friend Ben Reinhardt points out that most visions of success are hazy at first; he argues that the real difference is whether you start out with a plan or not. In terms of public affairs, maybe the best way to think about this is the degree to which you think you know the concrete steps that need to be taken in order for the world to improve.

It occurs to me that all of these types of optimism have their uses, but in different situations. For people with clinical depression, who often suffer from persistent negative narratives, indefinite optimism of the intellect can be very helpful — the simple realization that things generally aren’t as bad as they seem can act as a lens through which all the events of life seem less catastrophic.

For people just starting out on solving a hard problem like climate change, where the solution isn’t yet apparent, an indefinite optimism of the will might be more appropriate — you don’t know what the solution is yet, but you’re determined to find it.

If you’re already doing all you can for the world, but the news is still getting you down, you might want a definite optimism of the intellect. For example, suppose you’re a battery engineer working hard every day to replace fossil fuels, who nevertheless is upset at the slow pace of policy change. It might help you stay motivated to keep an eye on the things that are going right, like bolder emissions pledges and faster progress in technology.

And if you’re in a situation where you know what you need to do to make the world better, but are daunted by the sheer scale and difficulty of the task, a definite optimism of the will could be just the push you need to get moving.

Now let’s think about these in the context of big national problems like inflation, war, and unrest.

Two historical parallels

The U.S. has faced several deeply troubled periods in its history, where it looked like the country might come apart. In the 20th century there were two such episodes — the Depression and WW2 being the first, and the 1970s being the second. In these eras, the leaders who eventually steered us out of those difficult periods both promoted optimism, but of very different varieties.

In the Depression, Roosevelt and his administration committed to a program of optimism of the will. The New Deal was a strongly activist program — it was clear that the laissez-faire policies of Coolidge and the halfhearted activism of Hoover were insufficient, and so Roosevelt and his administration tried a whole bunch of different stuff, from bank holidays to fixing prices to getting off the gold standard to building infrastructure to creating Social Security. This was often an indefinite sort of optimism, because they didn’t know what would heal the economy, and resolved to simply try things until they figured out what worked. FDR described his approach in a graduation speech in 1932:

The country…demands bold, persistent experimentation It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something. The millions who are in want will not stand by silently forever while the things to satisfy their needs are within easy reach.

We need enthusiasm, imagination and the ability to face facts, even unpleasant ones, bravely…Yours is not the task of making your way in the world, but the task of remaking the world which you will find before you. May every one of us be granted the courage, the faith and the vision to give the best that is in us to that remaking!

It was this relentless drive to do something that won Roosevelt reelection twice, even though the Depression lingered.

When World War 2 came along, however, it became crystal-clear what the country needed to do: Defeat the Axis. The Roosevelt administration maintained a laser-like focus on this goal for four years, remaking much of the U.S. economy in the process. At this point, the main thing that was needed was simply the courage and will to push forward in the face of daunting challenges and terrifying enemies. FDR’s indomitable personality again served him well — Lyndon Johnson, who was in Congress at the time, later said that Roosevelt “was the only person I ever knew—anywhere—who was never afraid…God, how he could take it for us all.”

In the 70s, however, a similar approach didn’t seem to sit well with the American people. If you read the text of Carter’s “malaise” speech, you’ll notice that he calls for a national effort and shared national sacrifice in order to batter down high energy prices. In fact, Carter did deregulate energy, which probably helped a bit. And he took an activist approach toward inflation (by appointing the hawkish Paul Volcker to be Fed Chair) and growing Soviet power (by supporting rebels in Afghanistan). Ultimately, those efforts did yield results, especially against inflation.

But Carter did not win reelection. He lost to Ronald Reagan, a man whose optimism was decidedly of a sunnier, less activist sort. Reagan is often remembered for the “Morning in America” ad that he ran against Walter Mondale in 1984:

This seems like definite optimism, at least about evaluating outcomes; Reagan specifically praises lower inflation and lower interest rates as successes. But those were the successes of Volcker, a man Carter appointed, who did most of his rate hikes before Reagan even took office. So Reagan’s optimism in this ad is a bit passive.

And that generally fit the character of Reagan’s presidency. Though Reagan did cut taxes and engage in a modest defense buildup, his administration was often passive, choosing to wait problems out instead of pursue activist solutions. That worked with oil prices, when OPEC collapsed due to internal disagreements and new non-OPEC oil discoveries, and energy became cheap once again. And it worked with the USSR, which collapsed from its own systemic weaknesses and policy errors. Even in the economic sphere, Reagan’s program of tax cuts and light-touch regulatory enforcement relied on the initiative of the private sector to grow the economy. Nor did Reagan take vigorous steps to address social and economic inequalities, as Nixon and LBJ had tried to do.

So what kind of optimism does America need now?

Which brings us to the present day. It’s possible to make an argument that what we need right now is a Reagan-like approach of laid-back sunny restraint, to chase away the post-Covid mental demons.

You can argue that with core inflation falling, stimulus spending over, and supply chain problems resolving, there’s essentially little we need to do about rising prices other than to wait it out and keep an eye on expectations to make sure they don’t get out of control.

You can also argue that the pandemic is over, thanks to vaccines (and to the unvaccinated acquiring immunity the old-fashioned way), and now we simply have to excise the pandemic mindset.

You can argue that Russia is a colossus with feet of clay, and that all we need to do is support Ukraine with weapons and encourage Europe to rearm, and keep up the sanctions that are choking Putin’s war machine to death.

And finally, you can argue that America’s age of division and unrest simply needs a cooling-off period. If we’re currently in the equivalent of the bitter and exhausted mid-70s, maybe we need something like the silly, shallow, materialistic 80s to distract us from our unhelpful mindset of incipient civil war.

So maybe we need sunny, calm, passive optimism of the Reagan type.

Then again, you can argue that this is not simply a replay of the 70s — that we got lucky back then, and that we’re unlikely to muddle through this time without vigorous national effort.

You can argue that China is very much not Russia, and is indeed the most populous and economically powerful rival we have ever faced. It’s possible China’s rise will simply fall flat on its face of its own accord, but it’s a remote possibility on which to bet our future. That’s an argument for the U.S. government to do a lot more — to actively move supply chains out of China and into allied countries or back to the U.S., to build the kind of weapons that might help us thwart a Chinese attack on Taiwan, and to vigorously seek out and strengthen alliances in Asia.

You can argue that climate change was still a distant threat in 1980 but is bearing right down on us now, that this is crunch time and we need to deploy a lot more green energy very rapidly. Yes, a livable climate is now within reach thanks to improved technology, but we’re going to need to install that technology faster.

And you can argue that there are a whole host of other deficiencies and inequities in the U.S. economic system that were not present in 1980, which are generating strains that exacerbate our recurrent bouts of social unrest. We need to reduce the price of health care, we need to build a lot more housing, and we could sure use a simpler and more effective social safety net. Doing all that will take more than some crappy tax cuts. It’s time to build, build, build.

In truth I think that both of these sets of arguments are convincing. Our problem now is that we have some problems where what makes sense is to just maintain a positive outlook and wait for the problems to resolve themselves, but other problems where a more activist approach is needed. We need to manage the trick of calming society down while also mobilizing it for action against some looming threats. That’s going to be a difficult needle to thread, and will take some bold leadership. In the end, I suspect the most effective method will be to redirect America’s attention away from social conflict (where vigorous efforts often become a negative-sum game) and toward the problems that we can all solve together — strengthening the nation, creating abundance, and pushing technology forward. A judicious combination of passive and active optimism.

I realize, of course, that this is easier said than done.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK