Why The UK Is Exporting Refugees To Rwanda

source link: https://medium.com/@cailiansavage1/why-the-uk-is-exporting-refugees-to-rwanda-5990e0f05d36

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Why The UK Is Exporting Refugees To Rwanda

Although more complex than the media is suggesting, it’s still not an adequate solution

In the past week, the UK government has incited a firestorm of criticism for a new scheme in which some asylum seekers will be exported to Rwanda.

It has been condemned as cruel, wasteful, illegal, infeasible, and just downright absurd. In truth though, Britain’s scheme is not really all that different from what other rich nations have done for a long time — and it probably won’t be the last either.

For years, Britain has attracted large numbers of arrivals across the English Channel, most of whom come on boats organized by smuggling gangs. There has long been significant public debate about the true nature of most of these arrivals — are they refugees (in which case they may have a legal right to come to Britain), or simply illegal immigrants in search of better jobs?

The answer, as with most political questions, is probably “a bit of both.” British Home Secretary Priti Patel has claimed that 70% of Channel crossers are single, male, economic migrants.

Home Office stats do suggest that 90% of Channel crossers are male.

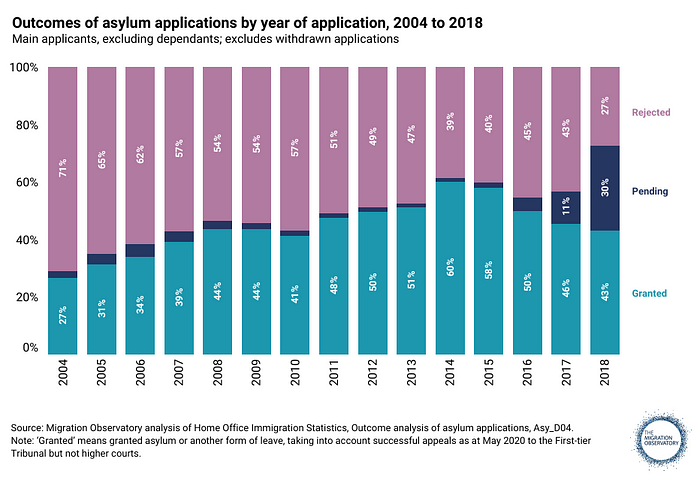

The University of Oxford’s Migration Observatory has compiled data on the success rates of UK asylum applications generally (but not for those crossing the Channel by boat specifically), which suggests that between 2004–2016, over 53% of applications were rejected (I have left out 2017 and 2018 due to a large number of pending cases).

Of those, some will be accepted on higher court appeal, though these figures take into account first-level appeals already.

For those crossing the Channel, the Director-General of UK Visas and Immigration stated in September 2020 during oral evidence to the Home Affairs Committee that of the 5,000 who had come over by boat at that point in the year, around 98% had claimed asylum.

Half of those had received an initial decision, the vast majority of which were rejections: 10% on the basis that they were not valid refugees, and another 70% on the basis that they may be, but responsibility for their claim belongs to another EU member state due to having passed through or applied for asylum in another country.

Given that crossing the Channel means one is already in France by default, these results are not surprising. International law does allow for refugees to pass through safe countries on their way to a final destination, but this is generally dependent on family connections in the final destination — presumably, this explains the 20% of accepted applications.

In summary, then, asylum seekers have a roughly 50/50 chance of being granted refugee status in the UK generally, and the odds are lower still for those crossing the Channel.

Priti Patel is probably in the right range when claiming that 70% don’t have the right to be in the UK, although calling them “economic migrants” is certainly inflammatory since a fair number of those will be entitled to asylum elsewhere, albeit often in poorer countries like Greece or Hungary with fewer job opportunities.

So if these migrants might be granted asylum elsewhere, why are they crossing the Channel to come to Britain? The UK isn’t noticeably richer than France, after all, so why make the extra journey?

Asylum seekers themselves mainly chalk their motivations up to

- language (the average asylum seeker is more likely to speak some English than French or Greek)

- family connections

- cultural factors, particularly that British society is more tolerant of religion in the public sphere than France, where the tradition of laïcité has made it harder for observant Muslims to integrate

It’s worth noting that in 2018 (80%) and 2019 (66%), a clear majority of Channel crossers were Iranians, who have few legal routes of applying for refugee resettlement in the UK while being based in Iran, but are quite likely to receive refugee status once on UK soil. Iranians are also more likely to have money to pay smugglers than those from poorer countries.

Since Covid, the nationalities of Channel crossers have become more diverse, as conventional refugee resettlement has been suspended. However, over 50% are still from countries in the Islamic world.

For some, there’s another reason for making the journey: the UK is easier to work clandestinely in than France (and most of Europe), due to the large informal economy and lack of compulsory ID cards.

That brings us to another tricky part of the whole discussion: what is to be done about failed asylum seekers? You might imagine that they are simply sent home.

The reality, however, is much thornier. Deporting migrants usually requires close relationships with the countries of origin, which have to agree to take back the failed asylum seekers. Britain tends to have strained relationships with the governments that asylum seekers hail from, such as Iran and Iraq, and many governments are disinterested in taking back deportees.

Further complicating the picture is that for those who should be processed in another EU country, it can be difficult to establish a chain of responsibility.

Clearly, those crossing the Channel by boat are more likely to be France’s responsibility than Britain’s (from a legal, if not a moral point of view).

However, France is probably also not most asylum seekers’ point of arrival into the EU. That point is more likely to be along an EU border, like Bulgaria or Greece.

Many countries that receive lots of early-stage asylum seekers (like Hungary or Poland) are vociferously opposed to hosting refugees, while others (like Greece and Italy) are simply overwhelmed and unable to physically process any more.

Add in the need for Britain to negotiate bilateral immigration agreements with numerous separate EU countries since Brexit, and it’ll come as little surprise that fewer than half of failed asylum seekers are actually removed from the UK. After Brexit, the number being sent back to the EU fell to 1%.

The current British government came to power partly on the back of a promise to control borders. Although those crossing the Channel in small dinghies probably have little impact on UK society or economics, their frequent and illegal arrival serves as a constant humiliation to the government, and a symbol of the impotence of the state to impose law and order.

That’s where Rwanda comes in.

Up to now, people have been willing to go to Britain, knowing that this will rarely lead to a worse outcome regardless of the outcome of their asylum claim.

The Rwandan scheme, however, would introduce a new consideration: although Rwanda is largely safe from conflict and religious persecution, and in fact already hosts ~130,000 refugees, it is still a very poor country, more so than most countries asylum seekers are leaving.

That means that Rwanda will still serve as a safe haven for an Iraqi escaping war, or an Iranian Kurd afraid of government prosecution.

However, if that Iranian wasn’t experiencing persecution, and was just hopeful of a more comfortable life in a rich country like Britain, they’d be insane to leave France and risk being sent to Rwanda, which is much less affluent than any EU country, or even Iran itself.

The facilities in Rwanda are only capable of hosting a few hundred asylum seekers, and the UK has stated that they will prioritize young men without a valid asylum claim. Once in Rwanda, they can go through the Rwandan asylum system. If successful, they’ll receive permanent residency and full working rights. If unsuccessful, they would supposedly be deported, although that would be unlikely in practice.

The UK has described this agreement as a trial, with the potential to be expanded to as many people as necessary over the coming years.

Notably, several other countries (like Denmark, and Israel) have either struck similar deals with Rwanda or are currently in the process of doing so.

In estimating the efficacy of these agreements, the most commonly studied example is Australia, which has offshore processing centers in Nauru.

The Australian scheme has been bitterly criticized too. It formerly operated processing centers in Papua New Guinea as well, now shut due to human rights abuses, and the facilities on Nauru have also been described as inhumane.

The Australian government counters these claims by stating that the Nauru scheme saves lives that would be lost on longer boat journeys to Australia.

Has the Australian scheme led to a reduction in asylum seekers? No, but it is widely recognized as having disrupted the trade of human smugglers, which is a core aim of the UK scheme. It’s also not really an apples-to-apples comparison, since those setting out for Australia are not leaving a safe, developed country like those in France are.

The scheme is likely to be expensive. The UK is investing £120 million over 5 years into Rwanda’s development, as well as agreeing to pay processing costs similar to those that would be incurred in the UK (£20,000 to £30,000 per head), scrapping any ideas that Rwanda might be an opportunity to cut costs.

Priti Patel still believes the scheme will save money overall; it might, but this is entirely speculative until we have evidence of a deterrence effect.

For now, Rwanda’s processing capacities suggest that very few asylum seekers will actually be sent there, and so the influx of boats will probably not slow anytime soon.

However, if the scheme is expanded, it could have a considerable effect on the tens of thousands of people in Britain who have been rejected asylum but are staying anyway, as well as new arrivals without valid grounds for claiming asylum. Faced with a choice between Sub-Saharan Africa or their home countries, they may well decide that their time in Britain is up.

That may eventually fulfill the government’s stated goals of disrupting human trafficking and expelling economic migrants, but it will do little to dissuade economic migrants with refugee claims in other countries.

Iraqis or Libyans with asylum rights in Greece or Italy will still come to Britain in search of friends and English-speaking jobs, safe in the knowledge that they can simply fly back to continental Europe if threatened with a one-way flight to Rwanda.

Furthermore, Iranians and Iraqis, even those with real ties to Britain, will continue to cross by boat until they have formal pathways of applying for resettlement as refugees from outside Britain, rather than applying for asylum (which requires being on British soil).

It’s good that Britain can negotiate seriously with Rwanda.

In the future, hopefully it will be able to negotiate seriously with the countries capable of actually solving the migration crisis: its neighbors in Europe, and the Middle-Eastern countries most of these asylum seekers hail from.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK