Holmes-land: Theranos, Polaroid and the legacy of dropouts

source link: https://uxdesign.cc/holmes-land-theranos-polaroid-and-the-legacy-of-dropouts-fec5a3926ad0

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Holmes-land: Theranos, Polaroid and the legacy of dropouts

Successful college dropouts, especially those from legendary institutions like Harvard or Stanford, are part of the origin story for Silicon Valley giants; Gates, Zuckerberg, Jobs, Dell, Brin, Page, Ellison all dropped out before starting the companies that made them extraordinarily wealthy and changed the world. It’s a tradition, hardly new, with varying results.

Watching the Elizabeth Holmes saga “The Dropout” is endlessly fascinating, as it has been since the very beginning of the story. “Bad Blood” (not the Taylor Swift song or the TV series about the Montreal mob, but John Carreyrou’s book) is a detailed profile of an elaborate fraud, played out in an operatic arc ending in the guilty verdict in 2022.

Elizabeth Anne Holmes could be the Bizarro World mirror (or the East Coast/West Coast mirror) of someone like Edwin Herbert Land, who invented the Polaroid camera among his more than 500 patents (second only to Thomas Edison). Both took on what seemed like an impossible idea, with enormous technical challenges, sparked by a simple personal tale: Holmes was scared of needles and was looking for a painless way to analyze blood and Land was intrigued by his 3-year old asking why she couldn’t instantly see the picture he had just taken of her on a holiday in 1942. He took a walk and solved, in his mind, the basic mechanics and chemistry of the instant picture.

Their similarities are as interesting as their wildly different results.

Land really did change the world with polarizing lenses used during WWII and by inventing the bridge technology between film and digital photography. At one point it was estimated that one half of all American households had a Polaroid camera, a simply astonishing factoid.

Edwin Land demonstrating the instant pictures from the Polaroid processNot quite the Theranos story; Holmes is likely headed to prison for defrauding investors.

Both dropped out of esteemed institutions (Land from Harvard, Holmes from Stanford) and neither was immune from some subterfuge to maintain an authoritative image; Land adopted ‘Dr.’ as his honorific, even though he never earned any college degree, and Holmes adopted a bizarre baritone, maybe from Maggie Thatcher’s example of a powerful woman operating in a man’s world.

Both their companies ended up bankrupt, Polaroid after decades of creating innovative products, Theranos without ever achieving anything other than infamy.

They have both come to symbolize the very American tendency to tackle the impossible…and one of them actually succeeded. The other has come to symbolize the downside of the vaporous morals of Silicon Valley, riding the ‘fake it til you make it’ wave to the very bottom.

They are both very American tales.

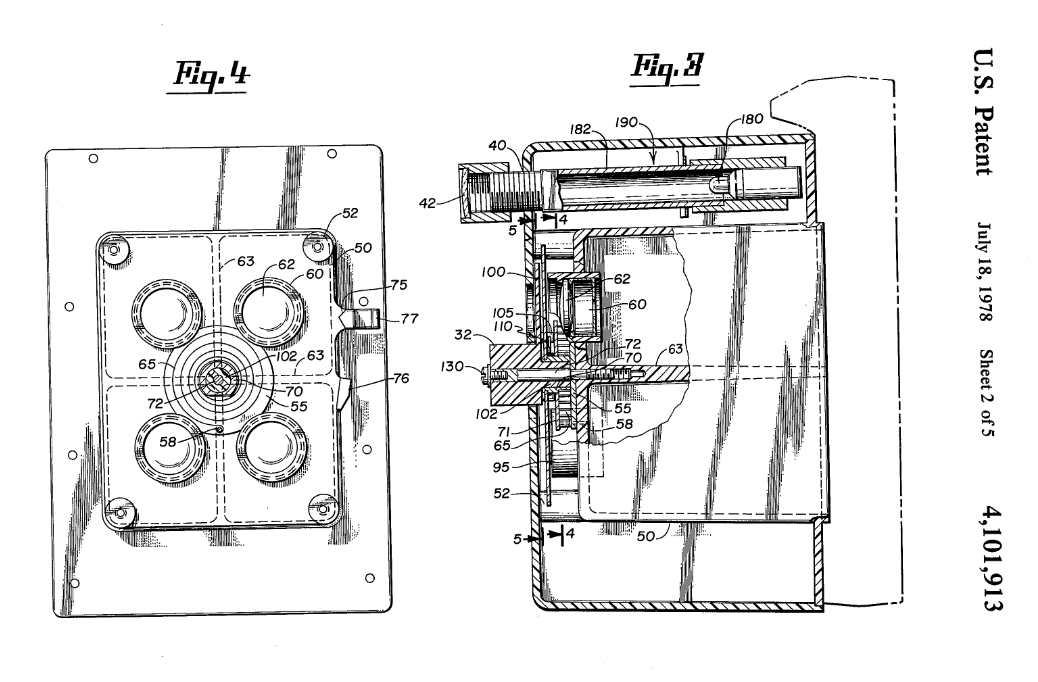

Both tried to tackle exceedingly complex and difficult engineering, but Land (who studied physics and optics at Harvard) actually designed solutions, while Holmes (who studied engineering at Stanford) did little more than define a product in search of a solution. Miniaturization of complex processes into tiny packages was the technical problem they shared; Land packed an entire darkroom process into a flat rectangle fed through a camera, Holmes attempted to fit the processes of an entire blood lab into a small box.

I would have bet on Holmes; it seems more attainable to shrink existing chemistry into a box, the way an entire room of computing power is now exceeded by the computing power in your phone, or watch. But shrinking increasingly speedy electronics and shrinking complex lab processes that require distributing blood and myriad procedures in rigidly controlled environments are two very different problems. The magic of instant pictures in an analog world, especially the later models like the extraordinary SX-70, developed in full daylight in front of your eyes is the height of conjuring. It is still, long after these devices have become functionally obsolete, fascinating to watch. And that whole ‘shake it like a Polaroid picture’ move is simply a bizarre dance to the magic of Land (in the Land of magic).

Elizabeth Holmes is no idiot, she didn’t just dream up some goal and wait for someone else to figure it out (well, not exactly); she studied engineering, she worked in labs, she knew enough to see the possibility and figure out paths to some solutions. Others told her it was impossible (in ‘The Dropout’ that’s Laurie Metcalf playing Phyllis Gardner)…but I’m pretty sure someone told Land he was fighting against basic optics and physics and couldn’t possibly succeed.

Land imagined (and solved) something that had never existed; pictures that were finished seconds after clicking the shutter. It was like a meal that made itself, cutting out the cooking process. He flattened time.

Holmes was determined to shrink every part of an already existing process, seemingly achievable in a world where products are regularly shrinking. But there are physical constants in blood assay that resist shrinkage. It’s a bit like the process of building on site; paint has to dry, concrete has to cure. There are physical constants that can be short circuited but not made to disappear. But one has to believer that there will, inevitably, be technology that makes it possible…just not today.

When I was in architecture school (a long time ago) one professor was fascinated/amused by a student who imagined a building process that was, in effect, a toothpaste tube dispensing its material in a continuous, mechanically programed stream from a central robotic arm, to construct a house, layer by layer like a coiled pot. It seemed to us all technically questionable and guaranteed to produce bad architecture. That was in 1972.

50 years later 3D printed buildings are being conceived and built in almost precisely the same way as the toothpaste buildings were to work. And now it seems both technically possible and architecturally fascinating. In the world of stick-built, prefab, manufactured, precut and modular homes, this is a potentially infinitely programmable, precise, rapid and feasible way to imagine the future of the home.

100 years ago Thomas Edison imagined a way to build houses out of concrete (he formed the Portland Cement Co. that supplied the concrete for Yankee Stadium before going out of business) in a single mono-material pour. It wasn’t just an idea. Edison built a number of these houses and many still exist (tearing down concrete houses is a bit more challenging than bulldozing a wood frame one).

Over a 100-year period this idea has been tried, failed, imagined and finally willed into its nascent being when the technology advanced sufficiently. It may be true (likely is true) of Holmes’s idea, but it may take decades to become reality.

There is no shame is imagining an unattainable future.

There is, however, considerable fraud in pretending that the future has arrived when it hasn’t.

There is a difference between real genius and potential genius, just as there is a difference between Land’s myriad inventions and Holmes’s handful of patents and unrealized ambitions. There is also a vast character difference between someone who worked hard to produce perfection and someone whose main aim was to ‘change the world and be a billionaire’ (but not necessarily in that order). She may have been a victim of an idea whose technology had not yet arrived, but she was sunk by a set of morals that had not yet arrived either.

Upbringing may not be everything, but compare the backgrounds of these two and there are perhaps hints at the future:

Land was raised by his Jewish parents in Norwich Connecticut, an industrial textile town; his father was a scrap metal dealer. Humble beginnings and an industrial town, but his brilliance shone through; it’s the American story. He loved to work hard, and after dropping out from Harvard as a freshman he invented a light polarizing film that was used in WWII and beyond, based on growing an array of tiny crystals as opposed to the large ones in use at the time. It was a brilliant insight, and it began the principle of R&D as the generator for developing products.

Land believed in basic research as integral to the future of industry, just as Bell Labs did when they worked, in effect, as the government’s R&D agency, developing things like the transistor, without retaining the intellectual property. Science was for the good of mankind and Edwin Land was in it for the knowledge and the science, for the inventions and of course for the products (but not for the fame or money, though he had plenty of both). As he said, he had “an urge to make a significant intellectual contribution that can be tangibly embodied in a product or process”. Hard to imagine Holmes making that claim.

Holmes was raised in Washington DC by a pair of powerful business/government parents, but the most telling factoid of her family is that her father was a VP at Enron, that paragon of corporate malfeasance. What more do you need to know? The Holmes family was well connected and well to do; respectable gangsters, perhaps, working in the public realm but comfortable with the peculiar lack of honor practiced in some corners of those worlds. Her mother was a congressional aide and her father eventually worked at various US agencies, like USAID. Was an embrace of the ‘unique ethical standards’ of Enron and of US politics part of what became the ‘Holmes Family Values’?

When we worked designing the USA Pavilion at the 2015 Expo in Milan, we spent a lot of time with State Dept. diplomats and staff (whose pavilion it was and who were, on the whole, wonderful people) and I remember one Deputy Commissioner General (or some such exalted title) summarizing all things diplomatic with one memorable phrase: “Well…” she said, “…The truth is elastic”. Fascinating coming from clearly very smart and dedicated people after working for years in a realm of malleable ethics.

It’s not hard to imagine that Elizabeth Holmes considered the truth to be elastic. If a test run by her micro labs worked once, but failed to work subsequently, it’s not hard to imagine her thinking that by faking results she was simply re-creating the past truth, not actually lying in the present. Just as Enron hadn’t really inflated profits, they just projected profits into the future and clawed those back into the present. These are the rationalizations of scoundrels who (the courts have proved) colored well outside the lines of legality.

Polaroid failed, after its decades of dominance, through a kind of technological fog; they understood the need for instant imagery, including motion imagery, but couldn’t make the leap from analog to digital. Land was a brilliant engineer, a brilliant man, but he was as tied to his conception of the world as Kodak, Xerox, Blockbuster, Motorola or Palm. These were enormously innovative companies that brought us part of the way to the future (our present) but couldn’t imagine, or couldn’t accomplish, the leap to a new way.

Theranos imagined a future beyond, it appears, the realm of current possibility, but decided that failure was not an option; without a moral compass lying about success was so much easier that actual success (and of course it is). My fave early burn of Theranos was in “Silicon Valley” the TV show, which has its star Thomas Middleditch say, in the 2016 finale of Season 3:

“Our platform does exactly what we say it does. It’s not like we’re lying about it like fucking Theranos.”

And scene.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK