Fifty percent of Facebook Messenger’s total voice traffic comes from Cambodia. H...

source link: https://restofworld.org/2021/facebook-didnt-know-why-half-of-messengers-voice-traffic-comes-from-cambodia-heres-why/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Fifty percent of Facebook Messenger’s total voice traffic comes from Cambodia. Here’s why

Share this story

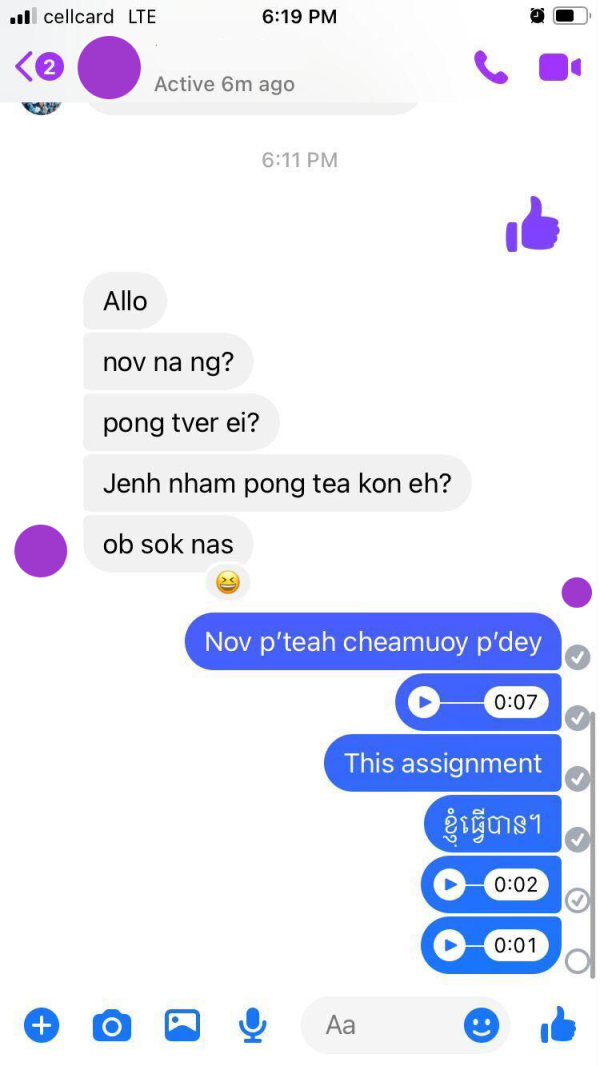

In 2018, the team at Facebook had a puzzle on their hands. Cambodian users accounted for nearly 50% of all global traffic for Messenger’s voice function, but no one at the company knew why, according to documents released by whistleblower Frances Haugen.

One employee suggested running a survey, according to internal documents viewed by Rest of World. Did it have to do with low literacy levels? they wondered. In 2020, a Facebook study attempted to ask users in countries with high audio use, but was only able to find a single Cambodian respondent, the same documents showed. The mystery, it seemed, stayed unsolved.

The answer, surprisingly, has less to do with Facebook, and more to do with the complexity of the Khmer language, and the way users adapt for a technology that was never designed with them in mind.

In Cambodia, everyone from tuk-tuk drivers to Prime Minister Hun Sen prefers to send voice notes instead of messages. Facebook’s study revealed that it wasn’t just Cambodians who favor voice messages — though nowhere else was it more popular. In the study, which included 30 users from the Dominican Republic, Senegal, Benin, Ivory Coast, and that single Cambodian, 87% of respondents said that they used voice tools to send notes in a different language from the one set on their apps. This was true on WhatsApp — the most popular platform among the survey respondents — along with Messenger and Telegram.

One of the most common reasons? Typing was just too hard.

In Cambodia’s case, there has never been an easy way to type in Khmer. While Khmer Unicode was standardized fairly early, between 2006 and 2008, the keyboard itself lagged behind. The developers of the first Khmer computer keyboard had to accommodate the language’s 74 characters, the most of any script in the world.

It was a daunting task. Javier Sola, a Spanish-born, Phnom Penh-based computer scientist, was part of the team working on the initial KhmerOS project in 2005.

“There are many, many more symbols in Khmer than in [the] Latin script,” Sola, now executive director of Cambodian NGO the Open Institute, told Rest of World . On a Latin keyboard, a user could see all of the alphabet at once, making typing intuitive. But in Khmer, each key hosted two different characters, which required flipping repeatedly between two keyboard layers. Not only that, but limited fonts meant that some messages failed to appear if the recipient’s computer lacked the same font as the sender’s. Still, users made it work.

Facebook became popular in Cambodia around 2009, just at the same time as cheap smartphones and internet access, which meant that its usage exploded. Today, it’s still the country’s most popular overall platform. But on a small smartphone screen, that same typing system became nearly impossible.

A 2016 USAID report showed that smartphone users preferred phone calls and voice messages because they found it difficult and time-consuming to type, or because they were confused about how to use the Khmer script on their device. Some respondents didn’t even realize their devices supported the language at all. Other functions that Western users take for granted — like accurate spell-checking or optical character recognition — still have only basic functions in Khmer, making it frustrating to text.

“There are slightly more advanced keyboards now,” said Sola, but they’re not pre-installed on phones — unlike Google, Samsung, and Microsoft keyboards. Over the years, habits have hardened into acceptance. In Cambodia, he said, voice messages are “just what people do.”

It’s not just Messenger. Users favor voice across Cambodia’s other popular platforms, Telegram, WhatsApp, and LINE. While updated voice traffic figures from Facebook aren’t available, Cambodians in the capital Phnom Penh told Rest of World that the overwhelming majority of people they knew relied on voice tools for both convenience and expressiveness. Rather than feeling cheated of functionality, users said that they preferred the personal, easy sensation of sending and receiving voice messages. On the whole, they’re not shy about talking in public, and are comfortable recording messages on the street.

Leng Len, a creative industry freelancer, said that it’s hard to go back. “It allows for the most organic expressions, and is quicker than typing,” she said.

But relying on voice tools also generates its own particular set of problems. Conversations become ephemeral. The same users also complained that they can’t scroll back to recall details of their exchange, and can only replay them by remembering the specific pattern of voice messages they left — one long and two short, for example. It’s impossible to use search functions for content in a chat history. Yet, at the same time, the inconvenience doesn’t appear to outweigh the drawbacks. Written messages now tend to be dominated by business or English-language exchanges.

While the Facebook employee imagined the behavior to be related to low literacy, Cambodia’s literacy rate is around 80%, according to the most recent World Bank data.

“Many young people, if they [do] want to type, will write out Khmer words in Latin text,” said Sok Pongsametrey, a Phnom Penh-based software engineer and chief operating officer at POSCAR Digital, a company that builds digital tools for education. Other times, if a letter is too difficult to spell, they may resort to spelling the word incorrectly using a more easily available character, or abbreviations of a word accompanied by ellipses, knowing that a reader will understand the implied word.

There are ripple effects. Sok said these types of workarounds make it more difficult for engineers working on machine learning to train AI in the language. He also worries that these shortcuts will mean that young people will lose their familiarity with the Khmer script.

“I am very careful when I write in Khmer, because it’s an art,” he said. “But, young people, they think [using Latin text] is easy.”

The mainstreaming of voice messaging in Cambodia raises questions over content moderation and the spread of misinformation. Audio is notoriously hard to scan, lacks contextual clues, and it’s difficult to tell when it’s been manipulated compared to video. “There are no jump cuts, like you’d see in a doctored video,” said Sam Gregory, U.S.-based program director at the NGO Witness.

Audio message evidence has featured in some high-profile cases, such as the reputation smearing of Luon Sovath, an activist Buddhist monk who fled Cambodia. He alleged that incriminating Messenger recordings had been fabricated by Cambodian authorities.

When asked about resources for this kind of moderation in Cambodia, a representative of Facebook, now known as Meta, only described general measures. “People can report any content on Messenger, including voice messages, and our team of native Khmer speakers will review and enforce against anything that violates our policies,” they said.

The spokesperson mentioned tools to detect harmful visual content, as well as hate classifiers, but didn’t specifically address Rest of World’s questions around audio moderation.

Javier Sola pointed out that there are newer keyboards like Microsoft SwiftKey that make it easier to type in Khmer, but many Cambodians don’t even know they exist. Default keyboards “don’t really adapt to user behavior. They just use the standard that we’ve had for almost 20 years,” said Sok.

Cambodia is just a market that many tech companies are not interested in developing better products for. “They’re not making money here, so they don’t invest,” said Sola.

And so Cambodian users continue to adapt instead. Asked if she thought voice messages would be superseded by better tech, Lam was doubtful. “I don’t think so. It helps facilitate more effective conversation.”

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK