Which SVG technique performs best for way too many icons? - Cloud Four

source link: https://cloudfour.com/thinks/svg-icon-stress-test/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Which SVG technique performs best for way too many icons?

Written by Tyler Sticka on October 28, 2021

When I started giving talks about SVG back in 2016, I’d occasionally hear a question I never had a great answer for: What if you have a lot of icons on a page?

You see, many attendees were interested in transitioning away from icon fonts. But while SVG offers a more accessible, reliable and powerful alternative, there’s no denying that browsers have an easier time displaying thousands of text characters than they do thousands of images (SVG or otherwise).

Still, it was an easy question to dodge. A typical inline SVG icon takes a fraction of a millisecond to render: When I’d ask the attendee what sort of interface required enough icons for that to add up, they’d admit that the question was hypothetical. I’d say something about the variety of SVG inclusion methods and the importance of performance testing, attendees would nod in a satisfied way and we’d all move on.

But then a few weeks ago, a client asked us to improve performance of a component that could include up to 200 rows of content, each row containing a handful of inline SVG icons. The improvements my talented colleagues eventually landed on would have more to do with DOM manipulation strategies than SVG, but along the way I was asked for advice: What’s the most performant method for including this many SVG icons at once?

It was time to stop dodging the question, roll up my sleeves and figure this out.

Considerations and caveats

This article focuses specifically on performance of large amounts of SVG icons.

If you have fewer than a hundred icons visible at a time, you probably don’t need to sweat your technique too much: The differences between one technique and another are a fraction of a millisecond per icon.

Icons are just one of SVG’s many use cases, some demanding greater complexity and their own performance considerations. For a great example of that, see Georgi Nikoloff’s article about SVG charts.

I won’t be comparing performance of SVG to other image or bundles formats. If you aren’t familiar with the pros and cons of SVG images, you can check out my talk and my team’s articles, read Chris Coyier’s Practical SVG and follow everything Sara Soueidan writes on the subject.

This many icons might hint at deeper design problems. You may be relying too much on iconography to communicate key concepts, or composing too many elements in a long scroll where pagination might be preferred.

Methodology

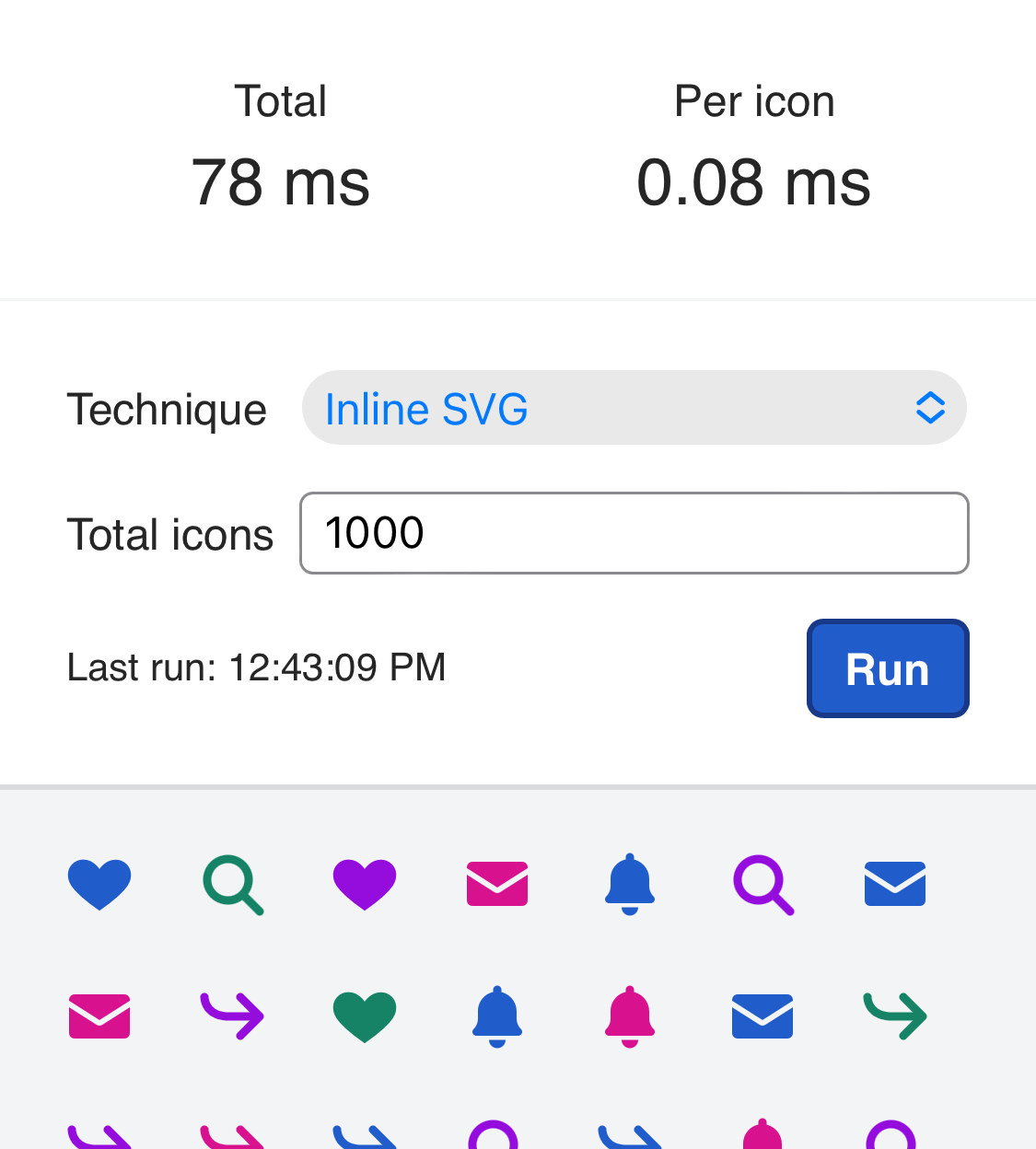

My test page uses vanilla HTML, CSS and JavaScript (to avoid any framework-related bias or side effects). It generates X number of HTML strings, shuffles the resultant array, appends the whole chunk of HTML, and reports the time taken to render.

The rendering time is determined by calling performance.now() on the animation frame before the HTML is appended, and again on the animation frame after. (The timestamp received by requestAnimationFrame isn’t used because it may be influenced by the display’s refresh rate, and even 16 milliseconds is enough to throw off results.)

For the results discussed here, two sets of icons were used. The first includes five optimized SVGs from our upcoming pattern redesign. The second set uses unoptimized versions of the same five: These were created by copying the contents of the optimized versions in Illustrator, pasting them into Sketch, and exporting without cleanup. These unoptimized versions have a bit of extra cruft (unnecessary group elements, masks and attributes) and a larger file size.

Icon Optimized size Unoptimized size arrow-down-right 296 Bytes 684 Bytes bell 488 Bytes 1.08 KB envelope 245 Bytes 1.21 KB heart 265 Bytes 946 Bytes magnifying-glass 254 Bytes 759 BytesYou can try the test page yourself (unoptimized icon version here), and the source is available on GitHub.

For each of the techniques I’ll discuss in this article, I tested 1,000 icons ten times per set in Chrome (Android, Mac), Edge (Mac), Firefox (Mac), Safari (iOS, Mac) and Samsung Internet (Android). I then compared the average and median results per technique, as well as the standard deviation to get a sense of consistency. You can view the full data set if spreadsheets are your jam.

Breakdown by technique

Inline SVG

An inline SVG is just an HTML svg element with its contents (paths, etc.) included directly within. There’s no fancy bundling or sprite strategy happening here: If the icon occurs many times on the same page, its contents are repeated each time.

<svg viewBox="0 0 24 24" width="24" height="24">

<!-- paths, shapes, etc. -->

</svg>

For the optimized icons, inline SVG was consistently one of the most performant techniques. But for the unoptimized icons, it was often the slowest.

Symbol Sprite

In this technique, the actual visual data of each icon is represented as a symbol element within a single SVG. Individual icons are displayed via a use element referencing the desired symbol.

<svg style="display:none">

<symbol id="example" viewBox="0 0 24 24" width="24" height="24">

<!-- paths, shapes, etc. -->

</symbol>

</svg>

<svg><use href="#example"/></svg>

The performance of this technique relative to Inline SVG seems to be dependent on the total number of elements reduced. For the optimized icons, this technique was always slower. For the unoptimized icons, it was often faster (though not consistently).

External symbol sprite

I also tested a variation of the previous technique where the symbol elements are stored in an external SVG file:

<svg><use href="path/to/sprite.svg#example"/></svg>

The results varied wildly between browsers. In Safari, external symbol sprites outperformed every other technique regardless of optimization. In Firefox and Samsung Internet Browser, external sprites modestly outperformed in-page sprites. But in Chrome and Edge, external symbol sprites were by far the slowest technique (and often the most inconsistent).

Image element

Like all image formats, SVG files may be displayed using img elements.

<img src="path/to/icon/color.svg" alt="">

Because the SVG is external, its contents can’t inherit in-page colors the same way that previous techniques can. For my tests, I generated static color variations of all icons, but this could also be accomplished using a microservice (like this one).

There are also slight differences in how image elements render compared to inline SVG: Negative space appears slightly diminished. This will be true for all remaining techniques in this article.

Enlarged comparison of icons rendered in Chrome. The top row are rendered as inline SVG, the bottom as external

img elements.This was one of the most performant techniques regardless of browser or optimization. That said, inline SVG has a slight edge when icons were optimized, and both techniques were consistently outperformed by our next option.

Image element with data URI

Because SVGs are composed of markup rather than bitmap data, they can be efficiently converted to a data URI string without any base64 encoding. This may be used to dynamically generate and/or colorize an SVG element without requiring an external service (or loading a separate file).

<img src="data:image/svg+xml;charset=UTF-8,..." alt="">

Across all browsers and regardless of optimization, this technique rendered the fastest and with the least deviation.

Image element with CSS filter

Monochromatic img elements may be colorized via a series of CSS filters, as demonstrated by Barrett Sonntag. This requires fewer unique images or data URI strings to begin with.

<img src="path/to/icon.svg" style="filter: ..." alt="">

This technique showed admirable performance in Chrome and Edge, middling performance in Firefox and Samsung Internet, and disappointing performance in Safari.

Background image

Like other image formats, SVG elements may be displayed as an HTML element’s background-image:

<div style="background-image: url(path/to/icon/color.svg);">...</div>

Background images are subject to the same limitations as img, with comparable rendering differences. Unfortunately, they do not yield comparable performance benefits, consistently under-performing compared to the image element and image element with data URI techniques.

I also tested this with a data URI, which performed slightly worse:

<div style="background-image: url(data:image/svg+xml;charset=UTF-8,...);">...</div>

And with filters, which performed significantly worse:

<div style="

background-image: url(path/to/icon.svg);

filter: ...;">...</div>

Mask image

Monochromatic images may be used as the value of a mask-image, reducing the visible area of the styled element to that of the icon. This preserves the ability to inherit the CSS colors while keeping the icon in a separate file.

<div style="

-webkit-mask-image: url(path/to/icon.svg);

mask-image: url(path/to/icon.svg);">

...

</div>

Whether using a static image or a data URI, this was generally the slowest technique.

And the rest…

SVG elements may also be displayed via object and iframe elements. I started adding tests for these, but the performance was so atrocious that I abandoned them quickly to focus on more viable options.

Other methods of bundling SVG sprites using a traditional background-image, fragment identifiers, SVG stacks or defs instead of symbol were omitted for being less common in 2021, more complicated to bundle and too similar to other techniques.

Takeaways

So which technique performs best for way too many icons? It depends!

If you want all the features of SVG and your icons are well optimized, inline SVG is your best bet. Simple and performant.

If your icons are complex or poorly optimized, or if you don’t need all the bells and whistles of SVG, image elements are the most performant option, especially using data URIs (encoded as escaped XML, not Base64).

No matter what technique you use, optimizing your SVGs will improve performance. Automated tools like svgo can help, but designers can make an even bigger difference by reducing elements and simplifying paths before export (see Sara Soueidan’s Tips for Creating and Exporting Better SVGs for the Web).

Acknowledgments

- Gerardo Rodriguez and Jason Grigsby for initial encouragement and direction.

- Paul Hebert, Scott Vandehey and Tim Kadlec for review and critique.

- Zach Leatherman for writing a webfonts article I used as a starting point for an outline.

- Aileen Jeffries for casually and unintentionally mentioning an oversight that was frustrating at the time but made the article much better!

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK