The big alcohol study that didn't happen: My primal scream of rage

source link: https://dynomight.net/alcohol-trial/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

The big alcohol study that didn't happen: My primal scream of rage

Oct 2021

What does drinking do to your health? We can say two things with confidence:

- Drinking is associated with lots of health problems.

- Heavy drinking is bad for you.

Here’s a graph of some associations.

Someone who averages 10 drinks per day is 50x more likely to get cirrhosis than someone who doesn’t drink at all (controlling for age, sex, and drinking history). This looks bad, but there are two caveats.

First, it doesn’t establish causality. It could be—if all you had was this figure—that cirrhosis causes hormonal changes that create urges to drink more.

But we do know that heavy drinking is bad. That’s partly because we know how alcohol causes problems. It causes cirrhosis by destroying liver cells. It causes cancer by getting converted to acetaldehyde and then damaging DNA. There are also randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that take heavy drinkers and get them to drink less. These inevitably show improved health (either health outcomes or biomarkers like blood pressure).

The second caveat is the little dip for diabetes and heart disease around 1-2 drinks. Some people think alcohol is causing this dip. Lots of mechanisms have been proposed: Maybe it reduces inflammation. Or maybe it impairs the cells that build up plaques in arteries. Or maybe it creates a hormonal imbalance that changes blood pressure regulation. Or maybe it increases HDL-cholesterol or insulin sensitivity or adiponectin levels.

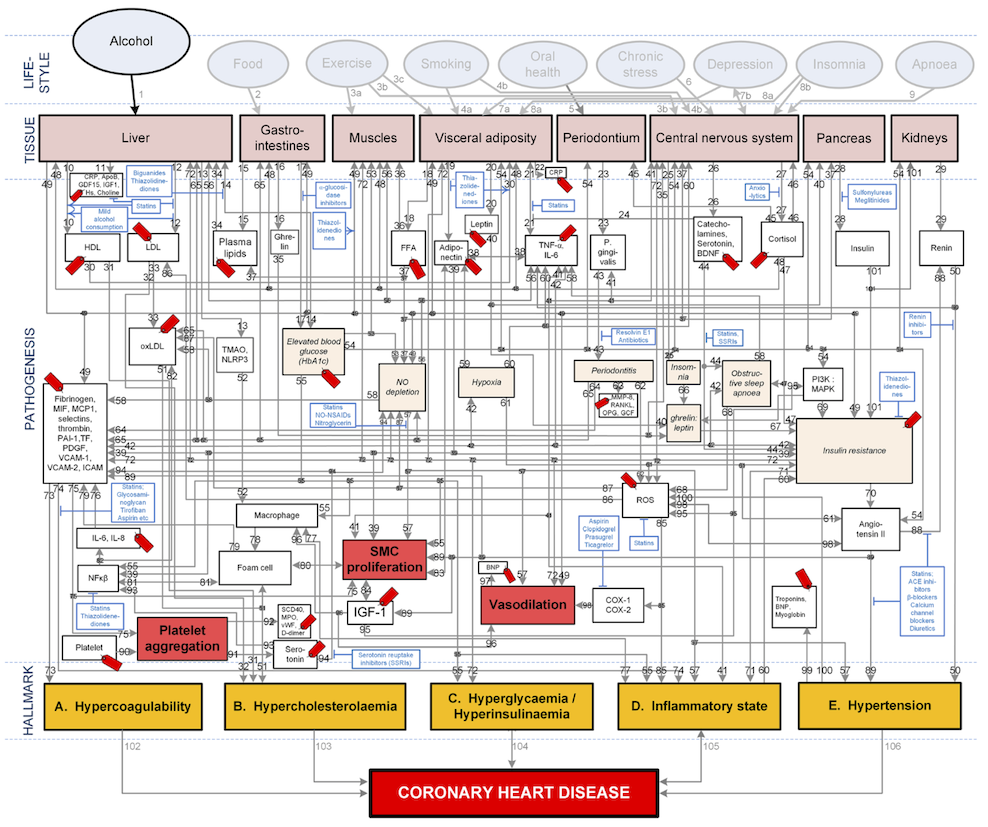

Or, maybe alcohol doesn’t help diabetes and heart disease at all. Mathews et al. (2015) try to model how alcohol affects the heart, ending up with this terrifying figure:

Alcohol does a lot of different things and interacts with a lot of other factors. It’s great to try to unravel all this, but I don’t trust anyone who says they understand everything with confidence.

If alcohol doesn’t improve heart health, then why the dip? Well, it could just be that the same people who drink moderately also tend to exercise and eat well.

So we don’t know if moderate drinking is bad for you. It almost certainly causes harms like cancer, but it might help heart disease enough to offset those harms. In the US, around 20% of adults drink 1-2 drinks per day. Even if the effects are modest, the collective impact is huge. Second perhaps to caffeine, alcohol is humanity’s favorite drug. We need to know what it does.

This is the story of a trial that came close to answering this question and then exploded. At first, this looks like a story of simple corruption but when you look closely it’s a very complicated story of corruption.

We need an RCT

You might be thinking, “what we need to do is compare the health of people who drink different amounts, while controlling for income, diet, education, exercise, etc.” The problem is that to a first approximation, “controlling” for things doesn’t work. It requires tons of different assumptions, like what you control for, how you code stuff, and how you model everything. Reasonable people can disagree about those assumptions. For alcohol, reasonable people do disagree, and so they get estimates that are all over the place.

So what do we do? We take the long, slow, hard path:

- Get a large group of people.

- Tell some of them to drink moderately, tell the others not to drink at all.

- Wait years, monitoring people to make sure they are actually drinking (or not) like they’re supposed to.

- Follow up and see which group is healthier.

Lots of things make this hard. Because the expected effects aren’t huge, you need a large group of people. Because culture and genetics vary, you need people from around the world. Because diseases take a long time to show up, you need to wait years. And imagine the challenge of telling people how much to drink and then making sure they follow your instructions.

An international effort monitoring thousands of people around the world for years—does that sound expensive?

A solution

Back around 2013, the NIH’s National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) got interested in funding this. They figured it would cost on the order of $100 million for the full trial. This doesn’t seem crazy given the NIAAA’s $500 million annual budget, but the NIAAA has lots of other priorities and didn’t feel they had the money.

You know who has a lot of money, though? The alcohol industry. Worldwide, $100 million of booze is sold every 30 minutes. In principle, the industry could directly fund a study, but who would trust it?

In 2016, it looked like the NIAAA had found an elegant solution:

- Five alcohol companies would donate money for a trial.

- The NIH would ask researchers to send proposals for how they’d run a trial.

- The NIH would choose the scientifically best proposal, just like they do with any government-funded grant. The donors would have no influence on the process.

- The make the results trustworthy, there would be a “firewall”, with no communication between the industry and the research team.

Sounds promising. But if we go forward a couple of years, everything suddenly blows up.

June 15, 2018

What happened? You might imagine banal corruption, with cocaine and overseas bank accounts, but it’s nothing like that.

The real story is a much more interesting cocktail of science, academia, bureaucratic maneuvering, ambition, politics, capitalism, the “deep state”, secret emails, and slippery ethical slopes. It’s particularly interesting because it’s a huge stroke of luck that we know about any of this. You have to ask how often similar things happen and don’t blow up.

If you’re brave, you can read the 165-page report the NIH prepared before canceling the program. But I warn you: It’s mostly out-of-order redacted emails written by people who wanted to conceal what was happening. There’s an executive summary, but it’s written in a frustratingly “government” style. There are also newspaper stories, but they don’t try to reconstruct everything.

After spending way too much time reconstructing things, here’s the story as best as I can tell.

Timeline

If you want an even-more-obsessive amount of information about the timeline, you can click on (more) after each of the sections.

2001 - 2013. Kenneth Mukamal, a physician at Beth Israel medical center and faculty member at Harvard Medical School, publishes many papers that argue that moderate alcohol consumption has health benefits, usually for heart disease or diabetes. During the same period, John Krystal, a psychiatrist and professor at Yale publishes many papers on alcohol, mostly focusing on addiction and mental health. (Many other researchers will be involved in this study, but these two are most prominent.)

(more)

Early 2013. Some NIAAA staff are convinced that moderate drinking is good for you, and an RCT could prove it conclusively enough that doctors might recommend it to patients like they do with aspirin now. (We don’t know who these staff were, but Margaret Murray was probably among them.) They have the idea of getting the alcohol industry to fund the study but face two problems. First, the alcohol industry wants lots of details before forking over any cash. Second, the NIAAA isn’t allowed to solicit from industry. They try to get around these problems by having outside researchers (including Mukamal and Krystal) meet with industry to give details on how such a trial might work. This creates a dynamic where everyone (the NIAAA, the alcohol industry, Mukamal) wants to coordinate with each other, but maintain a pretense of being isolated. There’s lots of scheming about how information should flow to maintain this pretense.

(more)

July 12, 2013. After getting some positive feedback from the industry, NIAAA staff decide to create a “planning grant”. This was supposed to be open to anyone, but the staff conspire to steer the money to Mukamal by having a super-short deadline (overruled by NIH-central) requiring pre-approval (also overruled, sort of), and asking for a very specific clinical trial. Two staff go as far as to take fake “personal vacations” to travel to Boston and help Mukamal write the grant. When the window to apply for the grant closes on November 1, Mukamal is the only applicant.

(more)

November 21, 2013. There is a meeting at the Distilled Spirits Council in Washington, DC between the alcohol industry, the NIAAA, and three researchers, including Mukamal and Krystal. Someone from industry later reported to NIAAA staff that “he was tremendously enthused about the project” and that they would need similar meetings with other companies. He specifically wanted to hear more from Mukamal and Krystal. There was another meeting at the same location on Jan 28, 2014.

(more)

January 2014. The preliminary planning grant is reviewed. One reviewer was concerned about the alcohol industry, but NIAAA staff were able to exclude the reviewer from voting on procedural grounds. When responding to reviewer comments, Mukamal states that he “tried to be discrete [sic] about the industry stuff.” The grant is formally awarded on March 20, 2014.

(more)

February 26, 2014. There is a meeting in Palm Beach, Florida, including the alcohol industry, at least one NIAAA staffer, and outside researchers. Mukamal’s slides stated, “A definitive clinical trial represents a unique opportunity to show that moderate alcohol consumption is safe and lowers risk of common diseases.”

(more)

February 28, 2014. Wine Industry Insights publishes “US Govt Asking Industry To Fund Most Of $50 Million Alcohol/Health Study”, causing a ton of concern inside the NIAAA from people who didn’t know what was going on. The people involved openly discuss how to best conceal information.

(more)

June 21, 2014. There’s a meeting in Seattle, led by Mukamal, and including NIAAA staff and the alcohol industry. Afterward, representatives from industry send Mukamal a list of technical concerns about the design of the RCT, including what outcomes to measure, the treatment population, adherence, dropouts, monitoring, using beer vs. spirits, and incentives to participate. Mukamal sends back a detailed response, sort of saying “well, this is what I would do if I happened to win the grant…” and then giving some reasonable answers.

(more)

November-December, 2014. A large joint conference call is coordinated between the alcohol industry, NIAAA staff, and researchers including Mukamal. Here are three topics that industry asks about:

- Will the data be shared with other researchers? Mukamal states that they would make “controlled data sets” available one year after the study ends.

- Might industry funding call the study into doubt? Mukamal reassures that it’s fine because there will be a “firewall” between research and industry.

- Will results will be published even if they are negative? Mukamal says yes, but they will “most certainly” see a positive impact at least for diabetes.

February 26, 2015. Murkamal and NIAAA senior staffers coordinate edits to an email that will be sent to someone in industry. This email states that yes, they really need $100 million, and “one of the important findings will be showing that moderate drinking is safe.”

(more)

Oct 5, 2015. The NIAAA publishes the funding opportunity for the big RCT. The published document implies that only someone who won the earlier planning grant—meaning only Mukamal—should apply. In December, Mukamal applies, and in January the opportunity closes without receiving any other applications.

(more)

March-September 2016. The proposal is reviewed by the NIH, and eventually awarded to Mukamal. The project begins on September 30.

(more)

July 3, 2017. The New York Times publishes “Is Alcohol Good for You? An Industry-Backed Study Seeks Answers”. This quotes Margaret Murray of the NIAAA as saying that five companies had pledged $67.7 million, and has a lot of general skepticism of the reliability of industry-sponsored research. There’s this quote from George Koob, then director of the NIAAA:

“This study could completely backfire on the alcoholic beverage industry, and they’re going to have to live with it,” Dr. Koob said. “The money from the Foundation for the N.I.H. has no strings attached. Whoever donates to that fund has no leverage whatsoever — no contribution to the study, no input to the study, no say whatsoever.”

There’s also this:

Dr. Mukamal […] said he was not aware that alcohol companies were supporting the trial financially. “This isn’t anything other than a good old-fashioned N.I.H. trial,” he said. “We have had literally no contact with anyone in the alcohol industry in the planning of this.”

October 26, 2017. Wired publishes “A Massive Health Study on Booze, Brought to You by Big Alcohol”. Aside from more general skepticism of industry funding research, it also points out that Murray and Koob at the NIAAA seem to have a cozy relationship with the industry. It’s got some quotes from a researcher in South Africa that sort of make Mukamal look like a jerk, and finally this:

Yet when I spoke to Mukamal in February 2017, he said he didn’t know about the Foundation’s negotiation for industry contributions “until relatively recently.” […] “We have no contact with funders other than NIAAA itself whatsoever,” he wrote.

Feb 5, 2018. The trial begins enrolling patients.

March 17, 2018. The New York Times publishes “Federal Agency Courted Alcohol Industry to Fund Study on Benefits of Moderate Drinking”. They interviewed former federal officials and used Freedom of Information Act requests to get emails and travel vouchers related to the grant. This story reveals that, contrary to Mukamal’s claims, there were various meetings in 2013 and 2014. This includes a “working lunch” at the Beer Institute convention in Philadelphia that’s not in my timeline above because I can’t figure out when it happened.

March 20, 2018. Based on the previous above article, NIH director Francis Collins orders an investigation into the trial.

April 11, 2018. Collins appears before the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Labor, Health and Human Services to discuss the NIH’s budget. When asked about the trial, Collins responds that he is very concerned and is investigating the issue as a matter of priority. (You can watch the video here.)

May 10, 2018. The NIH suspends enrollment in the trial.

June 8, 2018. Anheuser-Bush pulls its funding.

June 15, 2018. Based on a recommendation from an NIH working group, Collins terminates the study.

Skepticism

You might think I’m out of my mind, but it’s hard for me to celebrate this trial being canceled. Obviously, lots of inappropriate stuff happened. But when you think about why you’d cancel the trial, the arguments aren’t as strong as you might think. Here are the arguments I’ve seen:

The NIAAA and Mukamal lied to the public.

True. They claimed this was just like any other NIH grant, where any researcher could propose a study design, and the NIH would choose the best entirely based on scientific merit. In reality, the NIAAA intentionally steered the money to one pro-alcohol researcher who coordinated the plan with the alcohol industry.

That was bad. But this doesn’t necessarily imply cancelation, if the study would have been useful. If the point is to punish people, let’s not hurt ourselves in the process, right?

If the study were done, no one would trust the results.

Possibly true, but let’s be careful. Are we claiming that no one should believe the results, or just that no one would? If it’s the latter, isn’t that kind of a weird reason to cancel a trial? Let’s break this down. Why might you not trust the results?

I don’t trust the research team.

Clearly, Mukamal thought the trial would show a benefit, but that doesn’t mean he was right. Anyone who’s worked in science knows what it’s like to confidently run an experiment, only to get smacked in the face by reality’s indifference to your pet theories and career goals.

But OK, say you don’t trust the research team. What do you think they are going to do, fabricate data? The study was a collaboration of a large team around the world. The data would be stored at a Data Management Center (whatever that is) at a different university and inspected every six months by a monitoring board. Here’s the organizational structure for the study:

This isn’t some excel spreadsheet stored on one grad student’s laptop. You’d need a big conspiracy.

Or maybe you don’t think they’d falsify data, but that for publication they would use some tortured data analysis to spin the results. The thing is, it’s not unusual to have researchers who want to find a given result—that’s every researcher everywhere! We have a system for this, which is that studies pre-register their statistical analysis. This study did that, and the plan seems fine (although, see below). There just aren’t many places to hide the bodies.

If the full data would have been public, that would be another major safeguard against selective data analysis, and made it even harder for anyone to fake things. I can't tell exactly what would have been public. Mukamal mentions making it public when planning the grant with industry. But then the actual grant proposal says nothing about it.

The study seems designed to deliver a pro-alcohol result.

Two concerns have been made about the study design. For one, it’s plausible that the biggest harms of alcohol (e.g. cancer) appear later, while cardiovascular and diabetes benefits (if they exist) happen quickly. So a five-year study might find alcohol reduces mortality while a ten-year study could show the opposite.

Fine, but what’s the principle here? Should we cancel all studies where there’s a much more expensive and difficult variant that would be more conclusive? We know this is an issue now, and we’d still know it when interpreting results after the study is done.

Another concern is that the study population maximizes the chances for alcohol to look good: It would only enroll people who are either ≥75 years old or at elevated risk for cardiovascular disease while excluding anyone with liver disease, a personal history of colon/liver/breast cancer, a family history of breast cancer, suicidal ideation, or dementia. If I wanted to maximize the chance that alcohol could be beneficial while minimizing the chance that alcohol could be harmful, this is the population I would choose.

If you want a final verdict on if moderate drinking is safe, I agree this seems like stacking the deck. I’d prefer a random sample of all adults. You can call this a “bias”. But you can also call it “refusing to take the sampling scheme into account when interpreting results”. There’s still value in knowing how alcohol affects a restricted population. And we can extrapolate—a neutral result in this study population would suggest alcohol is harmful to the average person.

You might also argue that it’s ethically required to exclude people who are at higher risk for being harmed by alcohol. I don’t really agree, but I’d imagine many people would.

The premise of the study is flawed: Recent evidence says alcohol is harmful to cardiovascular health.

This was brought up by the extra reviewers brought in to check the scientific merit of the study for the big NSF investigation. Some recent research suggests that alcohol could be bad for cardiovascular health. One strategy is “Mendelian randomization”: The ADH1B gene (which we’ve talked about before) makes it hard to metabolize alcohol. People who have it drink less. If you assume that gene is random in the population and that it’s causing reduced drinking, then you can treat it like a random assignment to drink less. Holmes et al. (2014) did this and found that carriers of ADH1B had better cardiovascular health by every measure. This suggests alcohol makes cardiovascular disease worse, not better. There’s also a recent meta-analysis of observational studies by Wood et al. (2018) that suggests that even small amounts of alcohol hurt cardiovascular health.

I don’t get this. Is the point that alcohol is definitely harmful? That’s wrong, the research in the previous paragraph is great, but it isn’t conclusive. Or is the point just that an RCT could fail to prove alcohol was helpful? Then… umm… isn’t that the entire point of doing the RCT?

The study would be misrepresented.

Imagine that the trial was done and that it showed little overall effect on health. Sure, you might say, you’ll remember that it used a special population and maybe didn’t run long enough to catch cancer. Clever people like you will interpret this as meaning that alcohol is probably harmful to the average person.

But do you trust journalists to understand these subtleties and convey them to the general public? Or would we just end up with headlines like “Gold-standard trial shows that moderate alcohol consumption is safe”?

This worries me, but less than you might think. For one thing, don’t most people already think moderate drinking is safe? The CDC just says not to drink more than 1-2 drinks a day. Tyler Cowen—the Internet’s greatest teetotaler—often points out the massive harms of alcohol. Yet he’s stated that he believes that by refusing to drink at all, he’s sacrificing a small amount of health.

Put that aside, though. Let’s make the logic more explicit: This is suggesting that because journalists might do something dumb, we should not run a trial that could give knowledge humanity has needed for generations.

Sure, I agree journalists might oversimplify things and confuse people. (Can anyone disagree given recent history?) I just don’t think that we can live in fear. We have to believe that once the scientific community has found the truth, it will eventually make its way into public consciousness. The solution to bad journalism is better journalism, not scientists refusing to do research on anything that could be misinterpreted.

It just looks bad.

The final NIH report notes that the researchers do not have “equipoise”. You could interpret this two ways. One, you might say the whole thing seems rotten and damn the logic of it. The other is that it looks bad for the NIH—that even if useful, it needs to be canceled to preserve trust in the institution. I understand this. But if that’s the reason to cancel, it makes me sad.

A defense of the main characters

When I first read about this trial blowing up, I was stupefied—how could everyone have been so shameless? What were they thinking?

Before criticizing people, it’s good to try to imagine the strongest defense of their actions. So let me try to do that here.

The alcohol industry

I mean, OK, this is an industry entirely devoted to selling an addictive substance that kills, by WHO estimates, three million people per year. Something like 75% of alcohol is sold to raging alcoholics. This isn’t a nonprofit organic vegetable farm. But we live in a capitalist system. We expect companies to try to make money, and selling alcohol is legal. Let’s not conflate this particular trial with general objections to the alcohol industry’s existence.

Think about their perspective. The NIAAA came to them and said, “We think moderate alcohol consumption is good for you! You should fund a trial to prove this. Win-win for everyone!” The NIAAA sent fancy researchers from fancy places to present to them. Those researchers told them, “I, fancy person, am sure moderate drinking is good! Give me money to prove it!”

The alcohol industry was straightforward they wouldn’t fund anything without knowing what would happen in the trial. The NIAAA could have given up at that point, but they bent the rules instead. The industry was worried, “Won’t it look bad that we’re funding this?” Again, they were told, “Nah, it’s fine! There will be a firewall!”

They were told by well-credentialed people that they could make money and do good at the same time. Is it so terrible that they believed them?

NIAAA staff

You might criticize NIAAA staff for becoming convinced that moderate drinking was healthy, even though the science is inconclusive. That’s bad, but if you criticize everyone who’s wrong about stuff, you’re not going to get much sleep.

You can also criticize them for stretching the rules and misleading the public. This is a more clear failing. But imagine you knew a study would be valuable, but there’s some bureaucratic rule that prevents you from doing it. Wouldn’t you be tempted to stretch the rules?

Think about the NIAAA staff who took “personal vacations” to visit Mukamal to help him write the original planning grant. When they did this, I bet they saw themselves as heroes. This is what you see in movies: There’s a big problem in the world. People in power know there’s a problem, but for institutional reasons, it’s hard to fix. Most of the people in power are blankfaces, more concerned with covering their asses than helping people. The heroes are the ones who are willing to bend the rules to solve the problem—even if that means taking on personal risks.

If you think that no one in government should bend any rules, then I bet you haven’t interacted with the government much. Often, the rules were made by people so removed from what’s actually happening that the abstractions in the rules don’t even make sense.

Here’s an example. Say you’re a scientist and you want to send a grant to the National Science Foundation (NSF). According to The Rules, you will propose a detailed plan of future work. In some (more theoretical) fields this is absurd: You have to do half the work in order to write that plan! And in other (less theoretical) fields, your grant will be reviewed by other scientists who will expect to see “preliminary work” to show your idea has promise. This leads to a funny situation where people do much of the research and then “propose” it afterward.

Everyone involved knows that this is happening! The grant reviewers aren’t fooled. The people at NSF aren’t fooled. (Though if they’ve been around for a while, they might not notice the doublethink anymore.) When Congress set up the NSF, they had a mental model of how research works. When that model doesn’t fit, people do the best thing they can: They collectively follow a parallel set of slightly different rules while simultaneously going through the motions of the rules as written. Congress didn’t mean to set up a system like this. Bending the rules allows their spirit to be followed as closely as possible.

At the NIAAA, The Rules say that you can’t solicit grants from industry. But what exactly is “soliciting”? You might imagine there’s some oracle somewhere ready to lend definitive answers, but I doubt it. Instead, what you probably see is some people doing things that are a little like soliciting, and it’s fine. Other people do things that look slightly more like soliciting, and again it’s fine. Eventually, someone pushes things slightly too far (or is just unlucky) and gets into trouble. The rules get clarified a bit then, but without acknowledging the institutional incentives that made everyone bend the rules in the first place. The person who got in trouble probably feels like a duck shot out of a flock.

So that’s what I guess happened at the NIAAA. The staffers are used to bending the rules because that’s what everyone does all the time because it’s the only way to do anything. They think that the alcohol study would be beneficial, and go for it, and over time things sort of spiral out of control.

Mukamal

There are lots of quotes from Mukamal where he appears to be promising to deliver a positive result. At first glance, these might look like red flags, but I don’t think they’re as bad as they seem.

For one thing, Mukamal didn’t start claiming alcohol was safe as a cynical ploy to get his hands on grant money. He had been publishing on the health effects of alcohol for years. There is no reason to doubt that he sincerely believed that moderate drinking had cardiovascular and diabetes benefits. (And he may well be correct!)

Can Mukamal be trusted? We can look at his track record. In 2007, he was first author on a paper that randomly assigned patients to consume black tea or not. They looked at tons of different biomarkers and found that the tea did… basically nothing. This is the kind of case where it would be easy to p-hack your way to force some conclusion, but they straightforwardly state they found no evidence.

So I don’t think these quotes represent a promise to falsify data but rather his confidence for what the study really would show when honestly performed.

Then there’s the lying. Mukamal said there was no communication with industry and that he had no idea industry funding was even involved. Lying is bad, but still: When Mukamal was describing a “firewall” between industry and research, he was probably thinking of a firewall that started existing sometime after industry committed to funding the study. As far as we know, such a firewall did actually exist: Mukamal wrote the final study plan without (further) interference from industry, and the trial would have run without any industry contact.

Would this “late firewall” have meant anything? Maybe so! The biggest question is if industry would have had an opportunity to bury the results if they didn’t look good. Maybe the firewall really would have stopped that.

So why did he hide the earlier meetings? Likely, Mukamal felt the public couldn’t handle it. Take a look at the first New York Times story on the subject. It is dripping with implications that the study is totally compromised when the only thing known (at the time) was that industry had funded things. It’s understandable that Mukamal might have felt that the media was out to get him.

So my guess is that Mukamal was basically a well-intentioned researcher who happened to have pro-alcohol views. He took an opportunity to try to prove his pet theory, and then kind of fell down a slippery slope where he was making gradually larger and larger ethical compromises in pursuit of a goal that he thought was worthy.

Having written that defense, I’d now like to explain why it’s wrong and I’m furious about every aspect of this story.

First, we can only compensate for biases if we know about them. I’m open to industry-funded research. I don’t necessarily mind a lead researcher who was chosen because they believe what industry likes. I can even live with industry having influence on the study design. I stubbornly hold all this even when the study has a goal of proving it’s safe to use humanity’s most harmful drug.

But my (possibly delusional) open-mindedness is based on the idea that it’s possible to compensate for the biases these issues create. That’s not possible if we don’t know about them. If you think research still has value despite these issues, fine, but you need to make that argument openly, not pretend the issues don’t exist.

Second, the firewall was fake. Say you’re OK with a “late firewall” where there’s tons of contact with industry early on, but no influence after the trial starts. This didn’t happen. How do I know? Well, did you notice the part where Anheuser-Bush pulled its funding? Having the power to shut down the entire trial whenever you want qualifies as influence.

Third, slippery slopes aren’t much of an excuse. Yes, we all face them, but that’s why it’s important to have principles—lines you won’t cross. If you haven’t run into one of those lines before you start lying to the New York Times, something is wrong.

Fourth, many people are complicit in silence. Maybe the alcohol industry really didn’t think anything underhanded was happening. Well, they knew on July 7, 2017, when the first New York Times story came out, including untrue or misleading statements from Mukamal and the NIAAA. They had months to correct the record, but they did nothing. The same is true for many of the other researchers involved.

Fifth, the general idea of industry funding with a firewall could be tremendously valuable but was tarnished by everyone here. Take nutritional supplements. Every time someone actually checks, we find out what’s in them bears little resemblance to what’s on the label (e.g. melatonin off by a factor of 10, or “ginkgo biloba extract” containing zero ginko biloba or tons of supplements containing heavy metals.) Some rare companies publish lab tests, but these always seem to be a test of some batch from two years ago by an unknown lab with no reputation who only tests three things and labels them “within spec”.

In principle, firewalled research could be the solution. Supplement companies could pay to have tests done by independent researchers. Consumers would have a quality signal for what products to trust, and the companies that make good stuff would make more money. Everyone would win (except the people selling crap products).

This trial has discredited this idea. Obviously, I blame the main characters, but the media is also part of this. Take the first New York Times article again. Remember that when this was written, the firewall was valid, as far as anyone knew. But the article is almost an editorial disguised as journalism. Besides mentioning that the study exists and is funded by industry (which is totally legit) it’s largely a collection of whatever random suspicious connections they could dig up between anyone even vaguely connected to the study and the alcohol industry. There are also quotes about how industry funding skews research, but it doesn’t engage with the fact that that’s why there was supposed to be a firewall in this case.

Obviously, I’m glad the New York Times followed up on this story and revealed holes in the firewall. I just wish there was a more nuanced tone that engaged with the premise that the problems with industry funding are possible to overcome, at least in principle.

Sixth, in the final review, the NIH made no attempt at cost/benefit analysis. Their final report is a fair summary of the problems with the trial. But it doesn’t consider the information that was lost by cancellation, or the fact that that there was little cost to taxpayers. (Though Collins’ letter to Senator Grassley reveals the NIH did pay around $4 million out of pocket.) Could a different principal investigator be put in charge? Could the study design be modified to address the concerns? Could the monitoring bodies have been strengthened so people could trust the results? Maybe the trial was unsalvageable, but it’s telling that the NIH didn’t bother to make that argument.

Finally, why have there been so few consequences? Collins says that “three individuals are no longer employed” at the NIH, and they made process changes to avoid similar problems in the future.

That’s something, but what about the researchers? To their credit, Harvard and Beth Israel did do an investigation of Mukamal, which led to him formally apologizing, and them putting in additional safeguards to make sure no future employees would do anything similar.

Hahahaha, no. Here’s what actually happened:

- Mukamal stated, “We stand fully and forcefully behind the scientific integrity” and “Every design consideration was carefully and deliberately vetted with no input or direction whatsoever from private sponsors.” (Yes, these are real quotes from after the study was canceled.)

- As far as we know, there were no investigations by Harvard, Beth Israel, or any of the other researchers’ institutions. No one faced any penalty of any kind.

- In 2020, in what might be the most brazen display of academic shamelessness in history, the researchers published a paper on how awesome the study would have been. Here’s a quote from that paper’s “sponsorship” section:

The Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (FNIH) supported the trial financially and managed contact between public and private organizations on behalf of NIH. The funds provided by FNIH for this project were contributed to FNIH by the brewing and distilling industries following contract negotiations that established an intellectual and financial firewall between MACH15 investigators and private contributors. The corporations providing support agreed to have, and had, no contact with trial investigators about any aspect of the study after their commitment of funding, and they agreed to receive no data or updates until they became publicly available. Ultimately, however, the most important safeguard for impartiality lies in the execution of a rigorous, transparent protocol following independent, expert peer review, and in the conduct of the statistical analyses as described in the protocol.

Emphasis mine. You can’t make this stuff up.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK