The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers

source link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41562-021-01196-4

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Results

We analysed anonymized individual-level data describing the communication practices of 61,182 US Microsoft employees from December 2019 to June 2020—data from before and after Microsoft’s shift to firm-wide remote work (our data on workers’ choice of communication media goes back only to February 2020). Our sample contains all US Microsoft employees except for those who hold senior leadership positions and/or are members of teams that routinely handle particularly sensitive data. Given the scope of our dataset, the workers in our sample perform a wide variety of tasks, including software and hardware development, marketing and business operations. For each employee, we observe (1) their remote work status before the COVID-19 pandemic, and what share of their colleagues were remote workers before the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) their managerial status, the business group they belong to, their role and the length of their tenure at Microsoft as of February 2020; (3) a weekly summary of the amount of time spent in scheduled meetings, time spent in unscheduled video/audio calls, emails sent and IMs sent, and the length of their workweek; and (4) a monthly summary of their collaboration network. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, managers at Microsoft used their own discretion in deciding whether an employee could work from home, which was the exception rather than the norm.

The natural experiment that we analysed came from the company-wide WFH mandate Microsoft enacted in response to COVID-19. On 4 March 2020, Microsoft mandated that all non-essential employees in their Puget Sound and Bay Area campuses shift to full-time WFH. Other locations followed suit and, by 1 April 2020, all non-essential US Microsoft employees were WFH full-time. Before the onset of the pandemic, 18% of US Microsoft employees were working remote from their collaborators. For this subset of employees, the shift to firm-wide remote work did not cause a change in their own remote work status, but did induce variation in the share of their colleagues who were working remotely. For the remaining 82% of US Microsoft employees, the shift to firm-wide remote work induced variation in both their own remote work status and in the remote work status of their coworkers.

We analysed this natural experiment using a modified difference-in-differences (DiD) model. Standard DiD is an econometric approach that enables researchers to infer the causal effect of a treatment by comparing longitudinal data from at least two groups, some of which are ‘treated’ and some of which are not. Provided that the identifying assumptions of the DiD model are satisfied, the causal effect of the treatment is obtained by comparing the magnitude of the gap between the treated and untreated groups after the treatment is delivered with the magnitude of the gap between the groups before the treatment is delivered. Our modified DiD model extends the standard DiD model by estimating the causal effects of changes in two different treatment variables (one’s own remote work status and the remote work status of one’s colleagues) and by introducing additional identifying assumptions such that it is possible to draw causal inferences in the presence of an additional shock (in our case, the non-WFH-related aspects of COVID-19) that affects both treated and untreated units, and is concurrent with the exogenous shock(s) to our treatment variables. The time series trends shown in Fig. 1 suggest that the identifying assumptions of our modified DiD model are plausible; further details on the model are provided in the Methods.

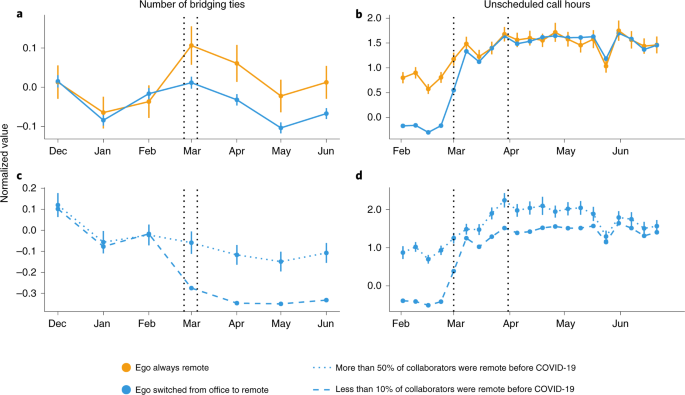

a–d, The average number of bridging ties per month (a,c) and the average unscheduled video/audio call hours per week (b,d) for different groups of employees, relative to the overall average in February. These plots establish the plausibility of the ‘parallel trends’ assumption that is required by our modified DiD model. The error bars show the 95% CIs and are in some places thinner than the symbols in the figure; s.e. values are clustered at the team level. a,b, The graphs show employees who, before COVID-19, worked from the office (blue; n = 50,268) and a matched sample of employees who worked remotely (orange; n = 10,914). c,d, The graphs show two subgroups of the blue lines in a and b—employees who, before COVID-19, had less than 10% of their collaborators working remotely (dashed; n = 36,008) and those who had more than 50% of their coworkers working remotely (dotted; n = 1,861). Both variables were normalized by subtracting and dividing by the average across the entire sample of that variable in February. Most employees transitioned to WFH during the week of 1 March 2020, although our analysis omits the month of March as a transition period.

In all of the analyses that follow, we cannot report the actual level of our outcome variables due to confidentiality concerns. Instead, throughout the paper we report outcomes and effects in terms of February value (FV)—the average level of that variable (for example, number of bridging ties) for all US employees in February.

Effects of remote work on collaboration networks

We start by presenting the non-causal time-series trends for different collaboration network outcomes across our entire sample. These trends provide insights into how work practices have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and also represent the type of data that many executives may use when making decisions regarding their firm’s long-term remote work policy.

Descriptive statistics

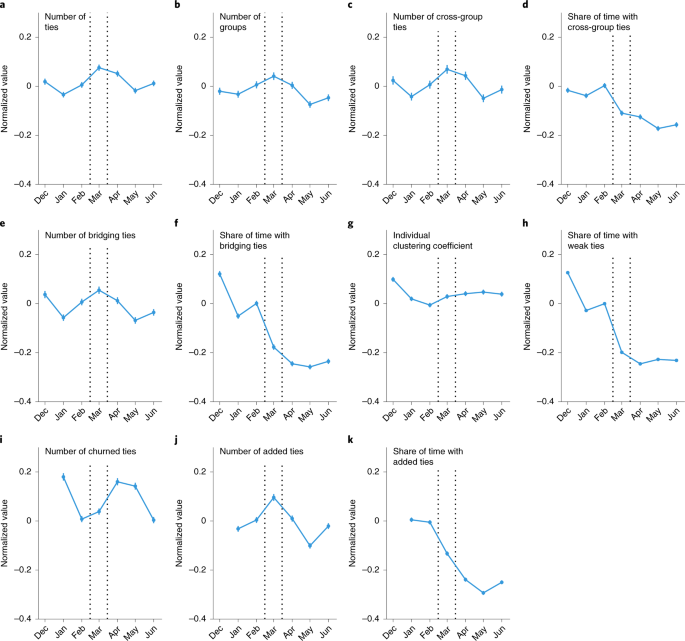

Figure 2 shows the average monthly time series for various aspects of workers’ collaboration egocentric (ego) networks from December 2019 to June 2020: the number of connections, the number of groups interacted with, the number of and share of time with cross-group connections, the number and share of time with bridging connections, the clustering coefficient, the share of time with weak connections, the number of churned and added connections, and the share of time with added connections. Mathematical definitions for these measures are provided in the Methods. Although we did not find evidence of a clear pattern of change around the shift to firm-wide remote work for many of these measures, we did observe large changes in the average shares of monthly collaboration hours spent with cross-group ties, bridging ties, weak ties and added ties, which all decreased precipitously between February and June.

a–k, The monthly averages for the collaboration network variables for all employees relative to the February average. Each variable was normalized by subtracting and dividing by the average FV for that variable. The vertical bars show the 95% CIs, but are in most places not much taller than the data points; s.e. values are clustered at the team level. The variables are employees’ average number of network ties (a), distinct business groups in which they have a collaborator (b), cross-group ties (c), ties that bridge structural holes in the network (e), individual clustering coefficient (g), collaborators from the previous month that they did not collaborate with that month (i) and added collaborators they did not collaborate with the previous month (j), as well as the share of time spent with cross-group ties (d), bridging ties (f), weak ties (h) and added ties (k). n = 61,279 for each panel.

Causal analysis

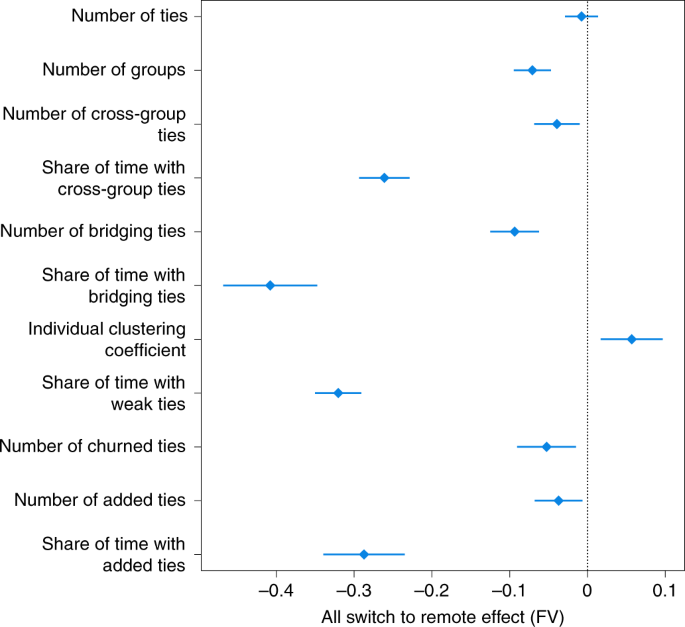

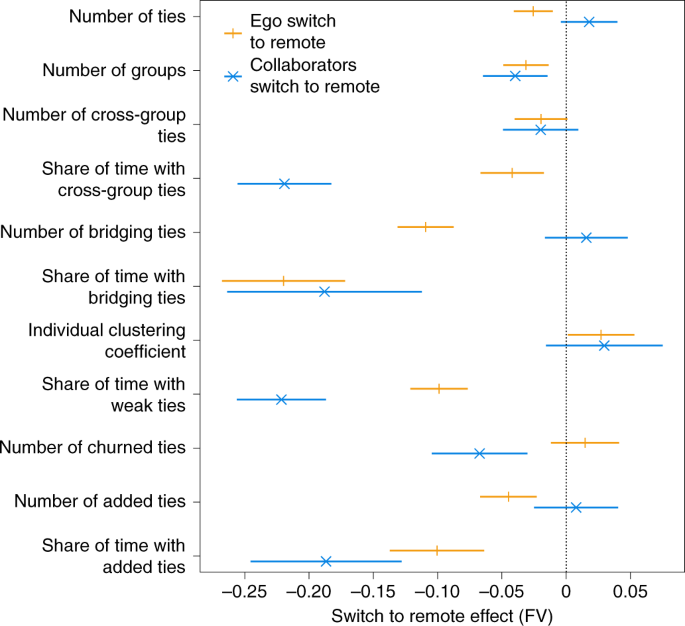

We next used our modified DiD model to isolate the effects of firm-wide remote work on the collaboration network, which are shown in Fig. 3. Although we found no effect on the number of collaborators that employees had (the size of their collaboration ego network), we did find that firm-wide remote work decreased the number of distinct business groups that an employee was connected to by 0.07 FV (P < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.05–0.10). Firm-wide remote work also decreased the cross-group connections of workers by 0.04 FV (P = 0.008, 95% CI = 0.01–0.07) and the share of collaboration time workers spent with cross-group connections by 0.26 FV (P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.23–0.29). In other words, firm-wide remote work caused an overall decrease in the number of cross-group interactions and the fraction of attention paid to groups other than one’s own.

The estimated causal effects of both an employee and that employee’s colleagues switching to remote work on the number of collaborators an employee has, the number of distinct groups the employee collaborates with, the number of cross-group ties an employee has, the share of time an employee spends collaborating with cross-group ties, the number of bridging ties an employee has, the share of time an employee spends collaborating with bridging ties, the individual clustering coefficient of an employee’s ego network, the share of time an employee spent collaborating with weak ties, the number of churned collaborators, the number of added collaborators and the share of time spent with added collaborators. The reported effects are (β + δ) from equation (1), normalized by dividing by the average level of that variable in February. The symbols depict point estimates and the lines show the 95% CIs. n = 61,182 for all variables. The full results are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Although formal organizational boundaries shape informal interactions40, the formal organization of firms and their informal social structure are two distinct, interrelated concepts41. Connections that provide access to diverse teams may not bridge structural holes in the network sense9, and connections that bridge structural holes in the network sense may not provide access to different parts of the formal organizational chart. We therefore also analysed how the shift to firm-wide remote work affected the structural diversity of employees’ ego networks with respect to the firm’s observed communication network, as opposed to the formal organizational chart. We label each tie as ‘bridging’ or ‘non-bridging’ on the basis of its local network constraint, which is a measure of the extent to which a given tie bridges structural holes in a network9,42. We then measured the effect of firm-wide remote work on the number of bridging ties that each worker had and the amount of time that each worker spent with their bridging ties. We found that, on average, firm-wide remote work decreased the number of bridging ties by 0.09 FV (P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.06–0.13) and the share of time with bridging ties by 0.41 FV (P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.35–0.47). The fact that firm-wide remote work caused workers to have fewer bridging ties, and to spend less time with their remaining bridging ties, suggests that firm-wide remote work may have reduced the ability of workers to access new information in other parts of the network. These results, in conjunction with our finding that firm-wide remote work reduced workers’ cross-group interactions, also suggest that firm-wide remote work caused the collaboration network to become more siloed, both in a formal sense and in an informal sense.

We also found that firm-wide remote work caused a 0.06 FV (P = 0.005, 95% CI = 0.02–0.10) increase in the individual clustering coefficient, which provides a measure of what proportion of an individual’s network connections are also connected to each other (the higher a person’s individual clustering coefficient, the more dense their ego network). Given the fact that we did not observe a statistically significant effect of remote work on the number of colleagues with whom workers collaborate, this result suggests that, on average, firm-wide remote work caused workers to substitute ties that were not connected to one another for those that were. In other words, different portions of the network, which became less interconnected, also became more intraconnected.

The ability of a worker to effectively access knowledge from other parts of an organization is a function of not only the organizational and/or topological diversity of their connections, but also the strength of those connections. For each month, we classified ties as strong when they were in the top 50% of an employee’s ties in terms of hours spent communicating, and as weak otherwise. Although we have not seen strong and weak ties defined in this exact way elsewhere in the research literature on social networks, the research community has not, to our knowledge, converged on a standard way to measure tie strength. Our operationalization is similar to a common tie strength definition that simply counts the amount of contact between ties43,44,45 and allows tie strength to vary over time on the basis of the relative amount of contact between two people46. Also, it is consistent with Granovetter’s original notion that tie strength is determined by a combination of “the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (mutual confiding) and the reciprocal services which characterize the tie”8.

Although weak ties by definition will always get less of an employee’s time than strong ties in a given month, we found that the shift to remote work reduced the share of time that workers spent collaborating with weak ties by 0.32 FV (P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.29–0.35). As the median is just one possible cut-off to distinguish between strong and weak ties, we also analysed the entire distribution of collaboration time for each worker and confirmed that the average ego-level-normalized Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI)47 of the collaboration time is increased by remote work, and that the average ego-level Shannon entropy48 of collaboration time is decreased by remote work. The effects of firm-wide remote work on both of these outcomes are provided in Supplementary Table 2. In total, these results indicate that, above and beyond the impact of firm-wide remote work on the organizational and structural diversity of workers’ ego networks, the shift to firm-wide remote work also made the allocation of workers’ time more heavily concentrated.

We also found that the shift to firm-wide remote work caused workers’ ego networks to become more static; firm-wide remote work reduced the number of existing connections that churned from month-to-month by 0.05 FV (P = 0.006, 95% CI = 0.02–0.09), and decreased the number of connections workers added month-to-month by 0.04 FV (P = 0.015, 95% CI = 0.01–0.07). Furthermore, the shift to firm-wide remote work decreased the share of time that workers spent collaborating with the connections they did add by 0.29 FV (P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.24–0.34). Of the added ties we observed in June 2020, 40% existed in at least one month between January 2020 and May 2020, whereas the remaining 60% did not. This suggests that the added ties that we observed are a mixture of dormant ties25 and ties that are truly new. Overall, the changes that we observed in the temporal dynamics of ego networks may have made it more difficult for workers to capture the benefits associated with forming new connections23,24, reconnecting with dormant connections25 and modulating their network position20,21,22. These results are robust to the use of alternative definitions of added and deleted ties (full details are provided in the Supplementary Information).

In summary, our results suggest that firm-wide remote work ossified workers’ ego networks, made the network more fragmented and made each fragment more clustered. We tested for heterogeneity in the effects of the shift to firm-wide remote work on collaboration ego networks with respect to a worker’s managerial status (manager versus individual contributor), tenure at Microsoft (shorter tenure versus longer tenure) and role type (engineering versus non-engineering), and did not find meaningful heterogeneity across any of these dimensions (Supplementary Figs. 1, 2 and 4).

The effects of remote work on the use of communication media

In addition to estimating the effects of firm-wide remote work on workers’ collaboration networks, we also estimated the impact of firm-wide remote work on workers’ choice of communication media.

Descriptive statistics

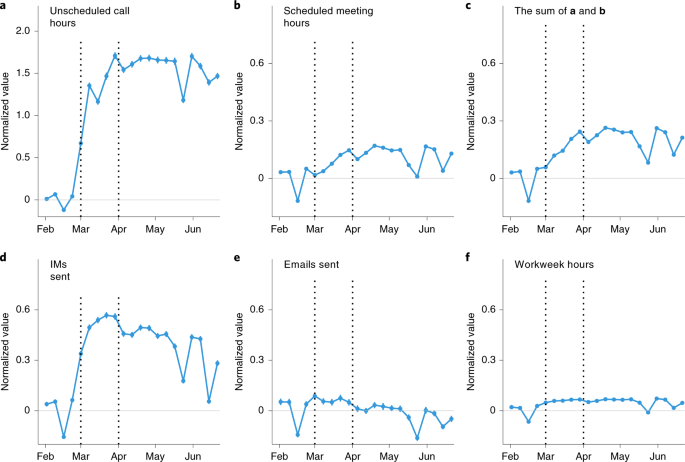

Figure 4 shows the non-causal time-series trends for workweek hours and different communication media outcomes across our entire sample. Detailed definitions for each of these outcomes are provided in the Methods. For unscheduled call hours, meeting hours, total video/audio hours and IMs sent, we observed considerable increases around the time of the switch to firm-wide remote work; these increases are sustained through our data timespan. The change in email volume is much smaller and shorter-lived. Figure 4f shows the change in workweek hours, a metric that measures the total amount of time between the first observed work activity and the last observed work activity on each work day in a given week. Although there was a sustained increase in workweek hours, it was too small to account for the large increases that we observed in the use of various communication media without a simultaneous shift in the way that employees were conducting work.

a–f, The weekly averages for each variable, relative to the February average. Each variable was normalized by subtracting and dividing by the average FV for that variable. The vertical bars show the 95% CIs, but are in most places not much taller than the data points; s.e. values are clustered at the team level. The variables are the employees’ average number of unscheduled audio/video call hours (a), scheduled meeting hours (b), total hours in scheduled meetings and unscheduled calls (the sum of a and b) (c), IMs sent (d), emails sent (e), and hours between the first and last activity (sent email, scheduled meeting, or Microsoft Teams call or chat) in a day, summed across the workdays (f). The dips in all six metrics during the weeks of 16 February, 24 May and 14 June were due to four-day workweeks, in observance of Presidents’ Day, Juneteenth and Memorial Day, respectively. n = 61,279 for all variables.

Causal analysis

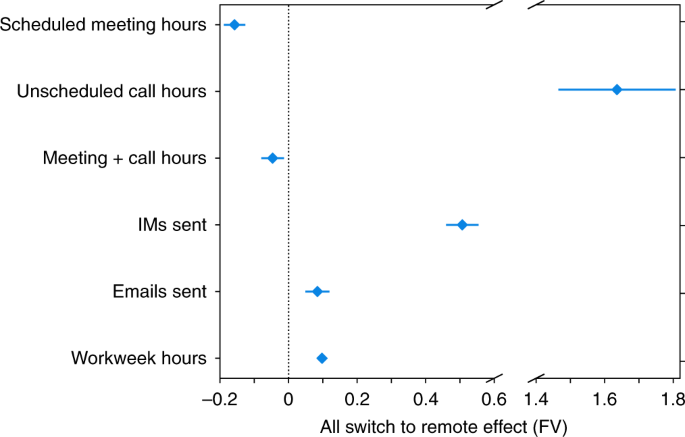

Figure 5 shows the estimated causal effects of firm-wide remote work on the amount of communication conducted through different media, as well as the length of workers’ workweeks. Relative to the baseline case of all coworkers working in an office together, we found that firm-wide remote work decreased scheduled meeting hours by 0.16 FV (P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.13–0.19) and increased unscheduled video/audio call hours by 1.6 FV (P < 0.001, 95% CI = 1.5–1.8). The increase in unscheduled calls was more than offset by the decrease in scheduled meeting hours. To observe that, we defined the sum of unscheduled call hours and scheduled meetings hours as the synchronous video/audio communication hours. We estimate that firm-wide remote work caused a slight decrease of 0.05 FV (P = 0.006, 95% CI = 0.01–0.08) in the total amount of synchronous video/audio communication. Given that, by definition, a shift to firm-wide remote work causes in-person interactions to drop to zero and synchronous video/audio communication decreased overall, our results also indicate that firm-wide remote work led to a decrease in the total amount of synchronous collaboration, both in-person and through Microsoft Teams.

The estimated causal effects of both an employee and their colleagues switching to remote work on the employee’s hours spent in scheduled meetings, hours spent in unscheduled calls, the sum of meetings and call hours, IMs sent, emails sent and estimated workweek hours. The reported effects are (β + δ) from equation (1), normalized by dividing by the average level of that variable in February. The symbols depict point estimates and lines depict 95% CIs. n = 61,182 for all variables. The full results are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Although firm-wide remote work caused a decrease in synchronous communication, it also caused an increase in the amount of asynchronous communication. Firm-wide remote work increased the number of emails sent by workers by 0.08 FV (P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.05–0.12) and the number of IMs sent by workers by 0.50 FV (P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.46–0.55). Firm-wide remote work also increased the average number of workweek hours by 0.10 FV (P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.09–0.11); however, this effect is small relative to the effect on IM volume. This suggests that the increase in IMs reflects a change in workers’ collaboration patterns while working, as opposed to changes in how much workers were working. The fact that shifting to firm-wide remote work increased the number of workweek hours also makes the negative effect of firm-wide remote work on synchronous collaboration more notable. The increase in workweek hours could be an indication that employees were less productive and required more time to complete their work, or that they replaced some of their commuting time with work time; however, as we are able to measure only the time between the first and last work activity in a day, it could also be that the same amount of working time is spread across a greater share of the calendar day due to breaks or interruptions for non-work activities.

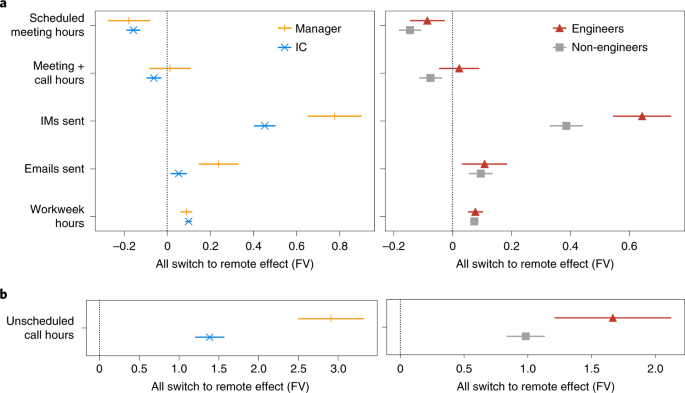

Heterogeneous effects of firm-wide remote work on communication media choice

Although the effects of firm-wide remote work on collaboration networks did not exhibit heterogeneity across the worker attributes that we observed, the effects of firm-wide remote work on communication media were in some cases larger for managers and engineers. We found that the switch to firm-wide remote work caused larger increases for managers than individual contributors in IMs sent, emails sent and unscheduled video/audio call hours (Fig. 6, left). This is probably because, relative to individual contributors, a larger share of managers’ time is dedicated to communicating with others, that is, their direct reports (for example, to address issues blocking progress or conduct performance reviews), and representatives of other groups within the organization (for example, to coordinate activity and goals across different groups). We also find that the shift to firm-wide remote work caused larger increases for engineers than non-engineers in the number of IMs sent and the number of unscheduled call hours (Fig. 6, right). This may be reflective of the fact that software development teams are particularly reliant on informal communication49,50,51, much of which may have taken place in-person before the shift to firm-wide remote work. We did not find meaningful heterogeneity with respect to employee tenure at Microsoft.

The causal effects, estimated separately for managers (n = 9,715) and individual contributors (ICs) (n = 51,467) (left) and engineers (n = 29, 510) and non-engineers (n = 31,672) (right), of an employee and their colleagues switching to remote work on hours spent in scheduled meetings, the sum of scheduled meetings and unscheduled call hours, IMs sent, emails sent and estimated workweek hours (a), and hours spent in unscheduled calls (b). The reported effects are (β + δ) from equation (1), normalized by dividing by the average level of that variable for all employees in February. The symbols depict point estimates and the lines show the 95% CIs. The full results are provided in Supplementary Tables 8, 9, 22 and 23.

Decomposing the effects of firm-wide remote work

One benefit of our empirical approach is that it enables us to decompose the causal effects of firm-wide remote work into two components: the direct effect of an employee working remotely on their own work practices (ego effects) and the indirect effect of all an employee’s colleagues working remotely on that employee’s work practices (collaborator effects). The model is linear, so the predicted effects from having half of one’s collaborators switch to remote work would be half as large.

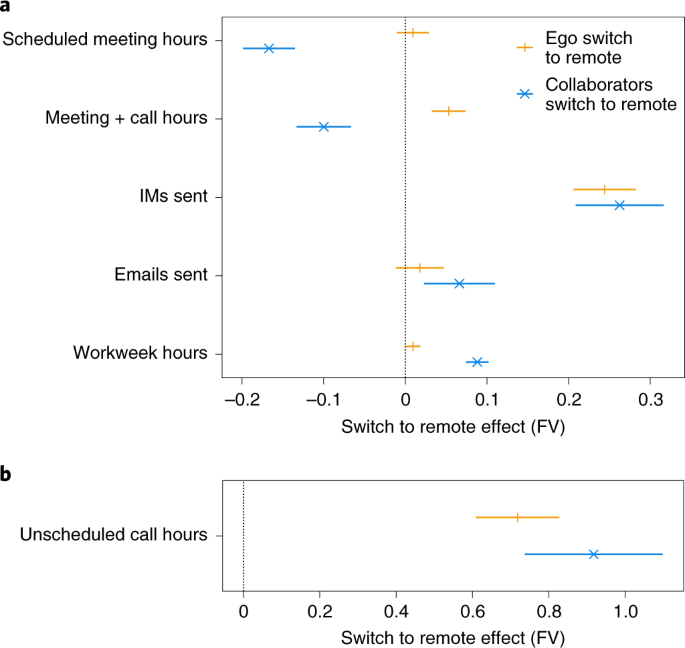

Figure 7 shows the ego and collaborator effects of firm-wide remote work on people’s collaboration networks. Notably, the remote work status of an employee and that employee’s collaborators both contributed to the total effect of firm-wide for most network outcomes. An employee’s collaborators switching to remote work seems to have had a particularly large impact on the amount of time that workers spent with ties that are most likely to provide access to new information, that is, cross-group ties, bridging ties, weak ties and added ties. As seen in Fig. 8, collaborator effects also dominate ego effects when we decomposed the effects of firm-wide remote work on communication media usage. More than half of the increase in IMs sent and emails sent was due to collaborators switching to remote work, and approximately 90% (+0.09 FV, P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.07–0.10) of the increase in workweek hours was due to collaborators switching to remote work. Overall, we found that collaborators switching to remote work caused workers to spend less time attending to sources of new information, communicate more through asynchronous media and work longer hours. Looking to the future, these findings suggest that remote work policies such as mixed-mode and hybrid work may have substantial effects not only on those working remotely but also on those remaining in the office.

The estimated causal effects of either an employee (δ from equation (1)) or their colleagues (β from equation (1)) switching to remote work on the number of collaborators that an employee has, the number of distinct groups the employee collaborates with, the number of cross-group ties an employee has, the share of time an employee spends collaborating with cross-group ties, the number of bridging ties an employee has, the share of time an employee spends collaborating with bridging ties, the individual clustering coefficient of an employee’s ego network, the share of time an employee spent collaborating with weak ties, the number of churned collaborators, the number of added collaborators and the share of time spent with added collaborators. All effects were normalized by dividing by the average level of that variable in February. The symbols depict point estimates and the lines show the 95% CIs. n = 61,182 for all variables. The full results are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

The estimated causal effects of either an employee (δ from equation (1)) or their colleagues (β from equation (1)) switching to remote work on hours spent in scheduled meetings, the sum of scheduled meetings and unscheduled call hours, IMs sent, emails sent and estimated workweek hours (a), and hours spent in unscheduled calls (b). All effects were normalized by dividing by the average level of that variable in February. The symbols depict point estimates and the lines show the 95% CIs. n = 61,182 for all variables. The full results are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

Recommend

-

6

6

Drag/drop effects: The little drop information box Raymond...

-

11

11

8 Lasting Effects of Remote Work That Will Reshape Workplaces Long gone are the days when we discussed how revolutionary it was for everyone to start working fr...

-

3

3

38% of remote workers work from bed

-

5

5

In this ProductTank London talk Ingrid Odegaard, Co-founder and CPTO at Whereby, shares some tips for making remote collaboration work on a day-to-day basis based on lea...

-

13

13

Tech at WorkAsk Help Desk: How remote workers can separate work and home lives Your most pressing tech questions answered by your...

-

6

6

Alan HenryIdeasJun 7, 2022 7:00 AM

-

4

4

-

6

6

There was a time when working from home was a pipe dream, but recently, there's been a surge of remote positions you can do from your own place. ...

-

5

5

Computer and Information Sciences degrees are the most loved among recent grads Top 10 most regretted and most loved college degrees By

-

1

1

7 Ways for Better Collaboration Among Your Testers and Developers ...

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK