Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and All...

source link: https://acoup.blog/2021/06/25/collections-the-queens-latin-or-who-were-the-romans-part-ii-citizens-and-allies/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Collections: The Queen’s Latin or Who Were the Romans, Part II: Citizens and Allies

This is the second part (I) of a series asking the question ‘Who were the Romans?’ How did they understand themselves as a people and the idea of ‘Roman’ as an identity? Was this a homogeneous, ethnically defined group, as some versions of pop folk history would have it, or was ‘Roman’ always a complex identity which encompassed a range of cultural, ethnic, linguistic and religious groups?

Last time, we presented the common pop-culture vision of the Romans, presented as a uniform or homogeneous cultural group, envisioned (especially in English-language productions) with white British actors speaking ‘the Queen’s Latin’ (that is, British English, often upscale and without strong regional accents). And we noted at the end that this depiction has filtered through into a certain set of folk historical theories about Rome, in particular the theory that Rome began as a homogeneous, ‘national’ state, achieved its conquests as a result of this supposed homogeneity, but then collapsed when it became multicultural due to its conquests. It’s a vision that imagines the Romans as a singular people who expanded outward militarily, but with an identifiable ethnic core.

Let anyone think I am tilting at strawman windmills here, I should note that within hours of that first post in this series going up, I got my first upset comment insisting that I had “either ignorantly or deliberately the differences between assimilable and un-assimilable cultural groups” and that such “un-assimilable” groups (the examples given being “Visigoths and the Jews” – because of course it’s the Jews, never mind that a Romanized Jew, Paul of Tarsus, is easily one of the most important historical figures of the last two thousand years and was by no means unique in his cosmopolitan outlook) became “a fifth column that destroyed Rome from within.” While we will not get to the Visigoths and the Jews today (though we will get to them later in the series), we’re going to see that this theory simply does not survive contact with the evidence in any meaningful way. But it is, I think, sustained by that deeply rooted pop-culture image which imagines the Romans exactly as they appear in film, TV and video games: as a bunch of white fellows speaking Latin with a British accent.

(As an aside, yes there are a lot of complications with terming this or that figure ‘Romanized’ which we’ll get to later. For now, I think it is sufficient to note that Paul had Roman citizenship, spoke Greek, had taken a Roman (Latin) name and was perfectly comfortable moving in non-Jewish circles in the Roman-controlled eastern Mediterranean.

Last time, we showed that far from beginning with an ethnically homogeneous core population, as this folk history theory supposes, every sort of evidence we have for early Rome, from the legends of the Romans themselves to the geographic, linguistic and archaeological evidence of the site, points to early Rome as a sort of ‘frontier town’ – a place defined as the meeting point of many quite different cultural groups. Unlike the poleis of the Greeks who, for all of their individual independence, largely shared a common religious and linguistic identity, these Italic peoples (who we’ll talk more about today) did not.

This week we’re going to march this story further, bringing our focus to how the Roman treatment of the different cultures of Italy evolved through the period of the Republic down to the mid-first century. That is unavoidably going to mean getting into some of the more legally dense concepts in Roman history, but I’ll try to keep this all approachable. In the end, understanding how Rome went from just one of Italy’s many self-governing cities to the dominant power in the Mediterranean requires understanding how the Romans handled all of those different Italian people as citizens and allies.

But first, as always, if you like what you are reading here, please share it; if you really like it, you can support me on Patreon. And if you want updates whenever a new post appears, you can click below for email updates or follow me on twitter (@BretDevereaux) for updates as to new posts as well as my occasional ancient history, foreign policy or military history musings.

Email Address

What is a Roman?

Before we do that, though, we need to set some ground-work into how ‘being Roman’ was defined. Roman wasn’t, after all, a linguistic grouping (that would be ‘Latin’ though as we noted, many Romans were not ethnic Latins), nor was it a religious grouping (Roman religion was highly syncretic, though as we noted, many Romans practiced other religions, in whole or in part). Nor was it purely a cultural marker; there were people who shared nearly all of ‘Roman’ culture who could not say ‘I am a Roman’ but – as we’ll see going forward – also people with very different cultures, languages and religions who could make that proudest boast, civis Romanus sum.

And that, it turns out, is the key to the question: ‘Roman’ was at its core a legal status, defined by citizenship which marked membership in a community. And so to ask the question ‘who was a Roman’ is to ask a question fundamentally legal in nature – and for this week, that’s how we’re going to treat the question. Of course that is not the only lens to view the issue; we’ll come back to Roman attitudes later in this series, including both Roman acceptance and Roman bigotry that formed in the situations where social assumptions (or raw snobbishness) and the legal status diverged.

But fundamentally, being Roman was about a legally defined community membership and so those are the terms we are going to approach today. How did Roman citizenship work and how did one get it and thus become a Roman? Because it turns out, by ancient standards, Roman citizenship was radically expansionary.

Ancient Citizenship

But before we dive into how Roman citizenship worked, we need to have a baseline for how citizenship worked in most ancient polities so we can get a sense of the way Roman citizenship is typical and the ways that it is different. In the broader ancient Mediterranean world, citizenship was generally a feature of self-governing urban polities (‘city-states’). Though I am going to use Athens as my ‘type model’ here, citizenship was not exclusively Greek; Italic communities; Carthage seems to have had a very similar system. That said, our detailed knowledge of the laws of many of the smaller Greek poleis is very limited; we only know that the Athenian system was regarded more-or-less as ‘typical’ (as opposed to Sparta, consistently regarded as unusual or strange, though even more closed to new entrants than Athens).

Citizenship status was clearly extremely important to the ancients whose communities had it. Greek and Roman writers, for instance, do not generally write that ‘Athens’ or ‘Carthage’ do something (go to war, make peace, etc), but rather that ‘the Athenians’ or ‘the Carthaginians’ do so – the body of citizens acts, not the state. Only citizens (or more correctly, adult citizen-males) were permitted to engage in direct political activity – voting, speaking in the assembly, or holding office – in a Greek polis; at Athens, for a non-citizen to do any of these things (or to pretend to be a citizen) carried the death penalty. This status was a jealously guarded one. It had other legal privileges; as early as Draco’s homicide law (laid down in 622/1) it is clear that there were legal advantages to Athenian citizenship. After Solon (Archon in 594), Athenian citizens became legally immune to being reduced to slavery; non-citizen foreigners who fell into debt were apparently not so protected (for more on this, see S. Lape, Race and Citizen Identity in the Classical Athenian Democracy (2010), 9ff). Citizenship, for those who had it, was likely the most important communal identity they had – certainly more so than linguistic or ethnic connections (an Athenian was an Athenian first, a Greek a distant second).

So then who got to be a citizen? At Athens, the rules changed a little over time. Solon’s reforms may mark the point at which citizenship became the controlling identity (Lape, op. cit. makes this argument). While Solon himself briefly opened up Athenian citizenship to migrants with useful skills, that door was soon slammed shut (Plut. Sol. 24.2); citizenship was largely limited to children with both a citizen father and a citizen mother (this seems to have been more flexible early on but was codified into law in 451/0 by Pericles). Bastards (the Greek term is nothoi) were barred from the citizenship at least from the reforms of Cleisthenes in 509/8. This exclusivity was not unique to Athens; recall that Spartiate status worked the same way (albeit covering an even smaller class of people). Likewise, our Latin sources on Carthage – no Carthaginian account of their government (or indeed any Carthaginian literature) survives – suggest that only Carthaginians whose descent could be traced to the founding settlers had full legal rights. Under the reforms of Cleisthenes (509/8), each Athenian, upon coming of age, had their claim to citizenship assessed by the members of their respective deme (a legally defined neighborhood) to determine if they were of Athenian citizen stock on both sides.

It is worth discussing the implication of those rules. The rules of Athenian citizenship imagine the citizen body as a collection of families, recreating itself, generation to generation, with perhaps occasional expulsions, but with minimal new entrants. Citizens only married other citizens because that was the only condition under which they could have valid citizen children. Such a policy creates a legally defined ethnic group that is – again, legally – incapable of incorporating or mixing with other groups. In this sense, Athenian citizenship, like most ancient citizenship, was radically exclusionary. Thousands of people lived permanently in Athens – resident foreigners called metics – with no hope of ever gaining Athenian citizenship, because there were no formal channels to ever do so.

Note: Really, we should speak in ranges, but it’s hard to convey that graphically. Estimates for the number of citizens range from 60,000 to 140,000 – but Thucydides’ figure (Thuc. 2.13.6-8) argues strongly for a number around 100,000, consistent with the c. 30,000 hoplites Athens was to have had. The number of metics is largely guesswork, but most estimates assume they are significantly outnumbered by the citizenry in the fifth century. It is also often assumed that the metic population was male-shifted, given who was likely to go abroad to do business in ancient Greece (but note also many metics were multi-generational residents of Athens).

The number of slaves is an unknown – the two ancient figures cited seem to be impossible on a population-density-basis. Probably the number of slaves equaled or even slightly exceeded the size of the citizen body.

The overall size of the population in Attica (the territory of Athens) should be somewhere between 200,000 and 300,000. I’ve gone with M. H.Hansen’s 1986 figures here – unfortunately, a lot of the newer work on Greek demography, like M. H. Hansen’s The Shotgun Method (2006) or J.-N. Corvisier La population de l’Antiquité classique (2000) are more focused on estimating total population, rather than population breakdown by social class.

I should also stress that estimates for the population of individual Greek poleis are deep guesswork. In many cases, Beloch (1886) – no, that is not a typo, 1886 – remains a standard reference.

(As an aside, it was possible for the Athenian citizenry to admit new members, but only by an act of the Ekklesia, the Athenian assembly. For a modern sense of what that means, imagine if it was only possible to become an American citizen by an act of Congress (good luck with the 60 votes to break a filibuster!) that names you, specifically as a new citizen. We don’t know exactly how many citizens were so admitted into the Athenian citizen body, but it was clearly very low – probably only a few hundred through the entire fourth century, for instance. In practice, this was a system where there were no formal mechanisms for naturalizing new citizens at all, that only occasionally made very specific exceptions for individuals or communities.)

In short, while there were occasional exceptions where the doorway to citizenship in a community might open briefly, in practice the citizen body in a Greek polis was a closed group of families which replaced themselves through the generations but did not admit new arrivals and instead prided themselves on the exclusive value of the status they held. The fact that the citizen body of these poleis couldn’t expand to admit new members or incorporate new communities but had become calcified and frozen would eventually doom the Greeks to lose their independence, since polities of such small size could not compete in the world of great kingdoms and empires that emerged with Philip II and Alexander.

(For further reading on citizenship in Athens and the evolution of law around it, C. Patterson’s chapter, “Athenian Citizenship Law” in The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Greek Law (2005), eds. M. Gagarin and D. Cohen is a good summary of what we know.)

Roman Citizenship

Roman citizenship worked very differently (obligatory note: some of this is going to get quite legal; since our knowledge of Roman law is best for the Late Republic and the Empire, that is what I am going to focus on.)

Not in the particulars of political participation. As with other ancient self-governing citizen bodies, the populus Romanus (the Roman people – an idea that was defined by citizenship) restricted political participation to adult citizen males (actual office holding was further restricted to adult citizen males with military experience, Plb. 6.19.1-3). And we should note at the outset that citizenship was stratified both by legal status and also by wealth; the Roman Republic openly and actively counted the votes of the wealthy more heavily than those of the poor, for instance. So let us avoid the misimpression that Rome was an egalitarian society; it was not.

The most common way to become a Roman citizen was by birth, though the Roman law on this question is more complex and centers on the Roman legal concept of conubium – the right to marry and produce legally recognized heirs under Roman law. Conubium wasn’t a right held by an individual, but a status between two individuals (though Roman citizens could always marry other Roman citizens). In the event that a marriage was lawfully contracted, the children followed the legal status of their father; if no lawfully contracted marriage existed, the child followed the status of their mother (with some quirks; Ulpian Reg. 5.2; Gaius, Inst. 1.56-7 – on the quirks and applicability in the Republic and conubium in general, see S.T. Roselaar, “The Concept of Conubium in the Roman Republic” in New Frontiers: Law and Society in the Roman World, eds. P.J. du Plessis (2013)).

Consequently the children of a Roman citizen male in a legal marriage would be Roman citizens and the children of a Roman citizen female out of wedlock would (in most cases; again, there are some quirks) be Roman citizens. Since the most common way for the parentage of a child to be certain is for the child to be born in a legal marriage and the vast majority of legal marriages are going to involve a citizen male husband, the practical result of that system is something very close to, but not quite exactly the same as, a ‘one parent’ rule (in contrast to Athens’ two-parent rule). Notably, the bastard children of Roman women inherited their mother’s citizenship (though in some cases, it would be necessarily, legally, to conceal the status of the father for this to happen, see Roselaar, op. cit., and also B. Rawson, “Spruii and the Roman View of Illegitimacy” in Antichthon 23 (1989)), where in Athens, such a child would have been born a nothos and thus a metic – resident non-citizen foreigner.

The Romans might extend the right of conubium with Roman citizens to friendly non-citizen populations; Roselaar (op. cit.) argues this wasn’t a blanket right, but rather made on a community-by-community basis, but on a fairly large scale – e.g. extended to all of the Campanians in 188 B.C.. Importantly, Roman colonial settlements in Italy seem to pretty much have always had this right, making it possible for those families to marry back into the citizen body, even in cases where setting up their own community had caused them to lose all or part of their Roman citizenship (in exchange for citizenship in the new community).

The other long-standing way to become a Roman citizen was to be enslaved by one and then freed. An enslaved person held by a Roman citizen who was then freed (or manumitted) became a libertus (or liberta), by custom immediately the client of their former owner (this would be made into law during the empire) and by law a Roman citizen, although their status as a freed person barred them from public office. Since they were Roman citizens (albeit with some legal disability), their children – assuming a validly contracted marriage – would be full free-born Roman citizens, with no legal disability. And, since freedmen and freedwomen were citizens, they also could contract valid marriages with other Roman citizens, including freeborn ones (note the caption below, for instance). While most enslaved people in the Roman world had little to no hope of ever being manumitted (enslaved workers, for instance, on large estates far from their owners), Roman economic and social customs functionally required a significant number of freed persons and so a meaningful number of new Roman citizens were always being minted in the background this way. Rome’s apparent liberality with admission into citizenship seems to have been a real curiosity to the Greek world.

These processes thus churned in the background, minting new Romans on the edges of the populus Romanus who subsequently became full members of the Roman community and thus shared fully in the Roman legal identity. But there was one other major way to become a Roman citizen, which was to be granted the status for services rendered to Rome. And for that we need to, at last, turn to the many other peoples of Italy and talk about…

The Allies

The Roman Republic spent its first two and a half centuries (or so) expanding fitfully through peninsular Italy (that is, Italy south of the Po River Valley, not including Sicily). This isn’t the place for a full discussion of the slow process of expanding Roman control (which wouldn’t be entirely completed until 272 with the surrender of Tarentum). The consensus position on the process is that it was one in which Rome exploited local rivalries to champion one side or the other making an ally of the one by intervening and the other by defeating and subjecting them (this view underlies the excellent M.P. Fronda, Between Rome and Carthage: Southern Italy During the Second Punic War (2010); E.T. Salmon, The Making of Roman Italy (1982) remains a valuable introduction to the topic). More recently, N. Terranato, The Early Roman Expansion into Italy (2019) has argued for something more based on horizontal elite networks and diplomacy, though this remains decidedly a minority opinion (I myself am rather closer to the consensus position, though Terranato has a point about the role of elite negotiation in the process).

The simple (and perhaps now increasingly dated) way I explain this to my students is that Rome follows the Goku Model of Imperialism: I beat you, therefore we are now friends. Defeated communities in Italy (the system is different outside of Italy) are made to join Rome’s alliance network as socii (‘allies’), do not have tribute imposed on them, but must supply their soldiers to fight with Rome when Rome is at war, which is always.

I make no apologies for this visual gag.

It actually doesn’t matter for us how this expansion was accomplished; rather we’re interested in the sort of order the Romans set up when they did expand. The basic blueprint for how Rome interacted with the Italians may have emerged as early as 493 with the Foedus Cassianum, a peace treaty which ended a war between Rome and Latin League (an alliance of ethnically Latin cities in Latium). To simplify quite a lot, the Roman ‘deal’ with the communities of Italy which one by one came under Roman power went as follows:

- All subject communities in Italy became socii (‘allies’). This was true if Rome actually intervened to help you as your ally, or if Rome intervened against you and conquered your community.

- The socii retained substantial internal autonomy (they kept their own laws, religions, language and customs), but could have no foreign policy except their alliance with Rome.

- Whenever Rome went to war, the socii were required to send soldiers to assist Rome’s armies; the number of socii in Rome’s armies ranged from around half to perhaps as much as two thirds at some points (though the socii outnumbered the Romans in Italy about 3-to-1 in 225, so the Romans made more strenuous manpower demands on themselves than their allies).

- Rome didn’t impose tribute on the socii, though the socii bore the cost of raising and paying their detachments of troops in war (except for food, which the Romans paid for, Plb. 6.39.14).

- Rome goes to war every year.

- No, seriously. Every. Year. From 509 to 31BC, the only exception was 241-235. That’s it. Six years of peace in 478 years of republic. The socii do not seem to have minded very much; they seem to have generally been as bellicose as the Romans and anyway…

- The spoils of Roman victory were split between Rome and the socii. Consequently, as one scholar memorably put it, the Roman alliance was akin to, “a criminal operation which compensates its victims by enrolling them in the gang and inviting them to share to proceeds of future robberies” (T. Cornell, The Beginnings of Rome (1995)).

- The alliance system included a ladder of potential relationships with Rome which the Romans might offer to loyal allies.

Now this isn’t a place for a long discussion of the Roman alliance system in Italy (that place is in the book I am writing), so I want us to focus more narrowly on the bolded points here and how they add up to significant changes in who counted as ‘Roman’ over time. But I should note here that while I am calling this a Roman ‘alliance system’ (because the Romans call these fellows socii, allies) this was by no means an equal arrangement: Rome declared the wars, commanded the armies and set the quotas for military service. The ‘allies’ were thus allies in name only, but in practice subjects; nevertheless the Roman insistence on calling them allies and retaining the polite fiction that they were junior partners rather than subject communities, by doing things like sharing the loot and glory of victory, was a major contributor to Roman success (as we’ll see).

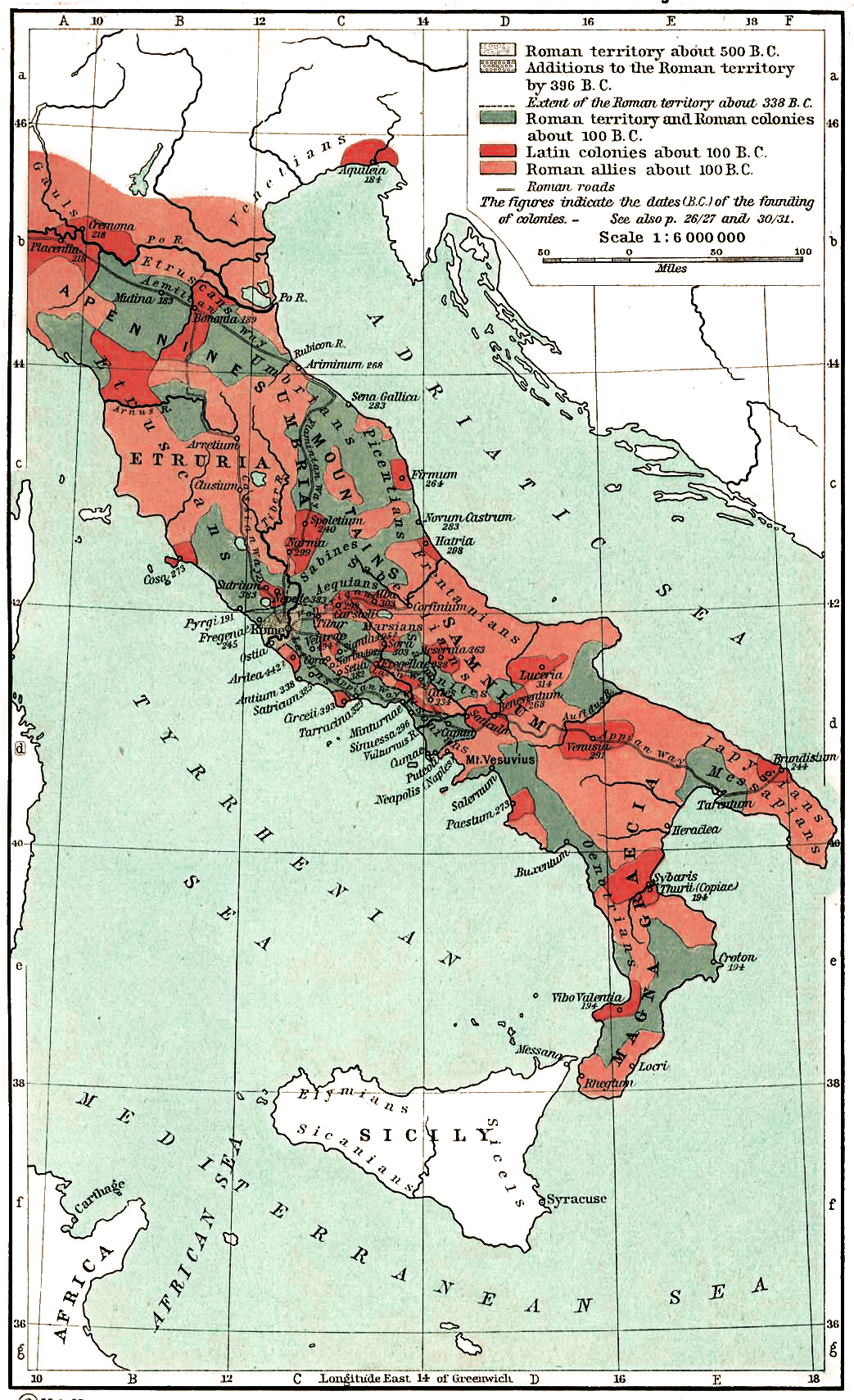

Via Wikipedia, a map of Roman territory in Italy at the end of the Second Century. Green areas are communities of Roman citizens, red areas are colonies with Latin rights, and the lighter red are communities of other socii.

Via Wikipedia, a map of Roman territory in Italy at the end of the Second Century. Green areas are communities of Roman citizens, red areas are colonies with Latin rights, and the lighter red are communities of other socii.

First, the Roman alliance system was split into what were essentially tiers of status. At the top were Roman citizens optimo iure (‘full rights,’ literally ‘with the best right’) often referred to on a community basis as civitas cum suffragio (‘citizenship with the vote’). These were folks with the full benefits of Roman citizenship and the innermost core of the Roman polity, who could vote and (in theory, though for people of modest means, only in theory) run for office. Next were citizens non optimo iure, often referred to as having civitas sine suffragio (citizenship without the vote); they had all of the rights of Roman citizens except for political participation in Rome. This was almost always because they lived in communities well outside the city of Rome with their own local government (where they could vote); we’ll talk about how you get those communities in a second. That said, citizens without the vote still had the right to hold property in Roman territory and conduct business with the full protection of a Roman citizen (ius commercii) and the right to contract legal marriages with Roman citizens (ius conubii discussed above). They could do everything except for vote or run for offices in Rome itself.

Next down on the list were socii (allies) of Latin status (note this is a legal status and is entirely disconnected from Latin ethnicity; by the end of this post, Rome is going to be block-granting Latin status to Gauls in Cisalpine Gaul, for instance). Allies of Latin status got the benefits of the ius commercii, as well as the ability to move from one community with Latin status to another without losing their status. Unlike the citizens without the vote, they didn’t automatically get the right to contract legal marriages with Roman citizens, but in some cases the Romans granted that right to either individuals or entire communities (scholars differ on exactly how frequently those with Latin status would have conubium with Roman citizens; the traditional view is that this was a standard perk of Latin status, but see Roselaar, op. cit.). That said, the advantages of this status were considerable – particularly the ability to conduct business under Roman law rather than what the Romans called the ‘ius gentium‘ (‘law of peoples’) which governed relations with foreigners (peregrini in Roman legal terms) and were less favorable (although free foreigners in Rome had somewhat better protections, on the whole, than free foreigners – like metics – in a Greek polis).

Finally, you had the socii who lacked these bells and whistles. That said, because their communities were allies of Rome in Italy (this system is not exported overseas), they were immune to tribute, Roman magistrates couldn’t make war on them and Roman armies would protect them in war – so they were still better off than a community that was purely of peregrini (or a community within one of Rome’s provinces; Italy was not a province, to be clear).

The key to this system is that socii who stayed loyal to Rome and dutifully supplied troops could be ‘upgraded’ for their service, though in at least some cases, we know that socii opted not to accept Roman citizenship but instead chose to keep their status as their own community (the famous example of this were the allied soldiers of Praenesti, who refused Roman citizenship in 211, Liv. 23.20.2). Consequently, whole communities might inch closer to becoming Romans as a consequence of long service as Rome’s ‘allies’ (most of whom, we must stress, were at one point or another, Rome’s Italian enemies who had been defeated and incorporated into Rome’s Italian alliance system).

But I mentioned spoils and everyone loves loot. When Rome beat you, in the moment after you lost, but before the Goku Model of Imperialism kicked in and you became friends, the Romans took your stuff. This might mean they very literally sacked your town and carried off objects of value, but it also – and for us more importantly – meant that the Romans seized land. That land would be added to the ager Romanus (the body of land in Italy held by Rome directly rather than belonging to one of Rome’s allies). But of course that land might be very far away from Rome which posed a problem – Rome was, after all, effectively a city-state; the whole point of having the socii-system is that Rome lacked both the means and the desire to directly govern far away communities. But the Romans didn’t want this land to stay vacant – they need the land to be full of farmers liable for conscription into Rome’s armies (there was a minimum property requirement for military service because you needed to be able to buy your own weapons so they had to be freeholding farmers, not enslaved workers). By the by, you can actually understand most of Rome’s decisions inside Italy if you just assume that the main objective of Roman aristocrats is to get bigger armies so they can win bigger battles and so burnish their political credentials back in Rome – that, and not general altruism (of which the Romans had fairly little), was the reason for Rome’s relatively generous alliance system.

The solution was for Rome to essentially plant little Mini-Me versions of itself on that newly taken land. This had some major advantages: first, it put farmers on that land who would be liable for conscription (typically placing them in carefully measured farming plots through a process known as centuriation), either as socii or as Roman citizens (typically without the vote). Second, it planted a loyal community in recently conquered territory which could act as a position of Roman control; notably, no Latin colony of this sort rebelled against Rome during the Second Punic War when Hannibal tried to get as many of the socii to cast off the Romans as he could.

What is important for what we are doing here is to note that the socii seem to have been permitted to contribute to the initial groups settling in these colonies and that these colonies were much more tightly tied to Rome, often having conubium – that right of intermarriage again – with Roman citizens. The consequence of this is that, by the late third century (when Rome is going to fight Carthage) the ager Romanus – the territory of Rome itself – comprises a big chunk of central Italy (as seen in the map below) but the people who lived there as Roman citizens (with and without the vote) were not simply descendants of that initial Roman citizen body, but also a mix of people descended from communities of socii throughout Italy.

Via Wikipedia, a map of the Ager Romanus (orange) and the Latin colonies (red-grey) by 218 (the eve of the Second Punic War). This map was made for J. Beloch’s Der italische Bund unter Roms Hegemonie (1880) but is still substantially accurate to what we know (and importantly for me, in the public domain).

Via Wikipedia, a map of the Ager Romanus (orange) and the Latin colonies (red-grey) by 218 (the eve of the Second Punic War). This map was made for J. Beloch’s Der italische Bund unter Roms Hegemonie (1880) but is still substantially accurate to what we know (and importantly for me, in the public domain).

So just who were all of these socii? Well…

A Word About the Socii

In one way, pre-Roman Italy was quite a lot like Greece: it consisted of a bunch of independent urban communities situated on the decent farming land (that is the lowlands), with a number of less-urban tribal polities stretching over the less-farming-friendly uplands. While pre-Roman urban communities weren’t exactly like the Greek polis, they were fairly similar. Greek colonization beginning in the eighth century added actual Greek poleis to the Italian mix and frankly they fit in just fine. On the flip side, there were the Samnites, a confederation of tribal communities with some smaller towns occupying mostly rough uplands not all that dissimilar to the Greek Aetolians, a confederation of tribal communities and smaller towns occupying mostly rough uplands.

In one very important way, pre-Roman Italy was very much not like Greece: whereas in Greece all of those communities shared a single language, religion and broad cultural context, Roman Italy was a much more culturally complex place. Consequently, as the Romans slowly absorbed pre-Roman Italy into the Roman Italy of the Republic, that meant managing the truly wild variety of different peoples in their alliance system. Let’s quickly go through them all, moving from North to South.

The Romans called the region south of the Alps but north of the Rubicon River Cisalpine Gaul and while we think of it as part of Italy, the Romans did not. That said, Gallic peoples had pushed into Italy before and a branch of the Senones occupied the lands between Ariminum and Ancona. Although Gallic peoples were always a factor in Italy, the Romans don’t seem to have incorporated their communities as socii; indeed the Romans were generally at their most ruthless when it came to interactions with Gallic peoples (despite the tendency to locate the ‘unassimilable’ people on the Eastern edge of Rome’s empire, it was in fact the Gauls that the Romans most often considered in this way, though as we will see, wrongly so). That’s not to say that there was no cultural contact, of course; the Romans ended up adopting almost all of the Gallic military equipment set, for instance. In any event, it wouldn’t be until the late first century BCE that Cisalpine Gaul was merged into Italy proper, so we won’t deal too much with the Gauls just yet. I do want to note that, when we are thinking about the diversity of the place, even to speak of ‘the Gauls’ is to be terribly reductive, as we are really thinking of at least half a dozen different Gallic peoples (Senones, Boii, Inubres, Lingones, etc) along with the Ligures and the Veneti, who may have been blends of Gallic and Italic peoples (though we are more poorly informed about both than we’d like).

Moving south then, we first meet the Etruscans, who we’ve already discussed, their communities – independent cities joined together in defensive confederations before being converted into allies of the Romans – clustered on north-western coast of Italy. They had a language entirely unrelated to Latin – or indeed, any other known language – and their own unique religion and culture. The Romans adopted some portions of that culture (in particular the religious practices) but the Etruscans remained distinct well into the first century. While a number of Etruscan communities backed the Samnites in the Third Samnite War (298-290 BC) culminating in the Battle of Sentinum (295) as a last-ditch effort to prevent Roman hegemony over the peninsula, the Etruscans subsequently remained quite loyal to Rome, holding with the Romans in both the Second Punic and Social Wars. It is important to keep in mind that while we tend to talk about ‘the Etruscans’ (as the Romans sometimes do) they would have thought of themselves first through their civic identity, as Perusines, Clusians, Populinians and so on (much like their Greek contemporaries).

Via Wikipedia, The Orator, a statue, c. 100 BC of an orator given as a votive offering. It is of Etruscan make (and has an Etruscan inscription) and draws heavily on Greek sculptural styles and motifs (like the contrapposto stance), though the orator in question wears the toga, often taken as a marker of Roman identity (its worth noting the toga, while often a symbol of Roman identity, could at times be a symbol of Italic identity; the Roman muster-list of Italian allies, for instance, was the formula togatorum, the ‘list of toga-wearers’). It is a brilliant example of cultural exchange and blending in Roman Italy.

Via Wikipedia, The Orator, a statue, c. 100 BC of an orator given as a votive offering. It is of Etruscan make (and has an Etruscan inscription) and draws heavily on Greek sculptural styles and motifs (like the contrapposto stance), though the orator in question wears the toga, often taken as a marker of Roman identity (its worth noting the toga, while often a symbol of Roman identity, could at times be a symbol of Italic identity; the Roman muster-list of Italian allies, for instance, was the formula togatorum, the ‘list of toga-wearers’). It is a brilliant example of cultural exchange and blending in Roman Italy.

Moving further south, we have the peoples of the Apennines (the mountain range that cuts down the center of Italy). The people of the northern Apennines were the Umbri (that is, Umbrian speakers), though this linguistic classification hides further cultural and political differences. We’ve met the Sabines – one such group, but there were also the Volsci and Marsi (the latter particularly well known for being hard fighters as allies to Rome; Appian reports that the Marsi had a saying prior to the Social War, “No Triumph against the Marsi nor without the Marsi”). Further south along the Apennines were the Oscan speakers, most notably the Samnites (who resisted the Romans most strongly) but also the Lucanians and Paelignians (the latter also get a reputation for being hard fighters, particularly in Livy). The Umbrian and Oscan language families are related (though about as different from each other as Italian from Spanish; they and Latin are not generally mutually intelligible) and there does seem to have been some cultural commonality between these two large groups, but also a lot of differences. Their religion included a number of practices and gods unknown to the Romans, some later adopted (Oscan Flosa adapted as Latin Flora, goddess of flowers) and some not (e.g. the ‘Sacred Spring’ rite, Strabo 5.4.12).

Also Oscan speakers, the Campanians settled in Campania (surprise!) at some early point (perhaps around 1000-900 BC) and by the fifth century were living in urban communities politically more similar to Latium and Etruria (or Greece, which will make sense in a moment) than their fellow Oscan speakers in the hills above, to the point that the Campanians turned to Rome to aid them against the also-Oscan-speaking Samnites. The leading city of the Campanians was Capua, but as Fronda (op. cit.) notes, they were meaningful divisions among them; Capua’s very prominence meant that many of the other Campanians were aligned against it, a division the Romans exploited.

The Oscans struggled for territory in Southern Italy with the Greeks – told you we’d get to them. The Greeks founded colonies along the southern part of Italy, expelling or merging with the local inhabitants beginning in the seventh century. These Greek colonies have distinctive material culture (though the Italic peoples around them often adopted elements of it they found useful), their own language (Greek), and their own religion. I want to stress here that Greek religion is not equivalent to Roman religion, to the point that the Romans are sticklers about which gods are worshiped with Roman rites and which are worshiped with the ritus graecus (‘Greek rites’) which, while not a point-for-point reconstruction of Greek rituals, did involve different dress, different interpretations of omens, and so on.

All of these peoples (except the Gauls) ended up in Rome’s alliance system, fighting as socii in Rome’s wars. The point of all of this is that this wasn’t an alliance between, say, the Romans and the ‘Italians’ with the latter being really quite a lot like the Romans except not being from Rome. Rather, Rome had constructed a hegemony (an ‘alliance’ in name only, as I hope we’ve made clear) over (::deep breath::) Latins, Romans, Etruscans, Sabines, Volsci, Marsi, Lucanians, Paelignians, Samnites, Campanians, and Greeks, along with some people we didn’t mention (the Falisci, Picenes – North and South, Opici, Aequi, Hernici, Vestini, etc.). Many of these groups can be further broken down – the Samnites consisted of five different tribes in a confederation, for instance.

In short, Roman Italy under the Republic was preposterously multicultural (in the literal meaning of that word)…and it turns out that’s why they won.

Roman Strength in the Crucible

With the end of the Third Samnite War in 290 and the Pyrrhic War in 275, Rome’s dominance of Italy and the alliance system it constructed was effectively complete. This was terribly important because the century that would follow, stretching from the start of the First Punic War in 264 to the end of the Third Macedonian War in 168 (one could argue perhaps even to the fall of Numantia in 133) put the Roman military system and the alliance that underpinned it to a long series of sore tests. This isn’t the place for a detailed recounting of the wars of this period, but in brief, Rome would fight major wars with three of the four other Mediterranean great powers: Carthage (264-241, 218-201, 149-146), Antigonid Macedon (214-205, 200-196, 172-168, 150-148) and the Seleucid Empire (192-188), while at the same time engages in a long series of often quite serious wars against non-state peoples in Cisalpine Gaul (modern north Italy) and Spain, among others. It was a century of iron and blood that tested the Roman system to the breaking point.

It certainly cannot be said of this period that the Romans always won the battles (though they won more than their fair share, they also lost some very major ones quite badly) or that they always had the best generals (though, again, they tended to fare better than average in this department). Things did not always go their way; whole armies were lost in disastrous battles, whole fleets dashed apart in storms. Rome came very close at points to defeat; in 242, the Roman treasury was bankrupt and their last fleet financed privately for lack of funds (Plb. 1.59.6-7). During the Second Punic War, at one point the Romans censors checked the census records of every Roman citizen liable for conscription and found only 2,000 men of prime military age (out of perhaps 200,000 or so; Taylor (2020), 27-41 has a discussion of the various reconstructions of Roman census figures here) who hadn’t served in just the previous four years (Liv. 24.18.8-9). In essence the Romans had drafted everyone who could be drafted (and the 2,000 remainders were stripped of citizenship on the almost certainly correct assumption that the only way to not have been drafted in those four years but also not have a recorded exemption was intentional draft-dodging).

And the military demands made on Roman armies and resources were exceptional. Roman forces operated as far east as Anatolia and as far west as Spain at the same time. Livy, who records the disposition of Roman forces on a year-for-year basis during much of this period (we are uncommonly well informed about the back half of the period because those books of Livy mostly survive), presents some truly preposterous Roman dispositions. Brunt (Italian Manpower (1971), 422) figures that the Romans must have had something like 225,000 men under arms (Romans and socii) each year between 214 and 212, immediately following a series of three crushing defeats in which the Romans probably lost close to 80,000 men. I want to put that figure in perspective for a moment: Alexander the Great invaded the entire Persian Empire with an army of 43,000 infantry and 5,500 cavalry. The Romans, having lost close to Alexander’s entire invasion force twice over, immediately raised more than four times as many men and kept fighting.

These armies were split between a bewildering array of fronts (e.g. Liv 24.10 or 25.3): multiple armies in southern Italy (against Hannibal and rebellious socii now supporting him), northern Italy (against the Cisalpine Gauls, who also backed Hannibal) and Sicily (where Syracuse threatened revolt) and Spain (a Carthaginian possession) and Illyria (fighting the Antigonids) and with fleets active in both the Adriatic and Tyrrhenian Sea supporting those operations. And of course a force defending Rome itself because did I mention Hannibal was in Italy?

Via Wikipedia, a map showing the socii who joined Hannibal after 216. The communities that did so represented perhaps a quarter to a third of all of the allies, meaning that Rome’s absurd mobilizations in 214 and 213 were made with a quarter or so of their manpower fighting against them.

Via Wikipedia, a map showing the socii who joined Hannibal after 216. The communities that did so represented perhaps a quarter to a third of all of the allies, meaning that Rome’s absurd mobilizations in 214 and 213 were made with a quarter or so of their manpower fighting against them.

If you will pardon me embellishing a Babylon 5 quote, “Only an idiot fights a war on two fronts. Only the heir to the throne of the kingdom of idiots would fight a war on twelve fronts.” And apparently, only the Romans would then win that war anyway.

(I should note that, for those interested in reading up on this, the state-of-the-art account of Rome’s ability to marshal these truly incredible amounts of resources and especially men is the aforementioned, M. Taylor, Soldiers & Silver (2020), which presents the consensus position of scholars better than anything else out there. I’d be remiss if I didn’t note that my own book project takes aim at this consensus and hopes to overturn parts of it, but seeing as how my book isn’t done, for now Taylor holds the field (also it’s a good book which is why I recommended it)).

How was this possible?

The answer very clearly comes down to the socii. Polybius preserves for us a fascinating bit of information here: in 225, the Romans took a census of every Roman liable for conscription but also had all of the socii do the same. There are some quirks to this data (by which I mean historians have been arguing about it for decades), but in brief, Polybius notes that the Romans figured they had 299,200 infantry and 26,100 cavalry liable for conscription. Of course these could not all be called up at once (someone needed to farm things, after all) and as a total this is not much more formidable than the ethnic Macedonian core of the Antigonid kingdom in Macedonia – the weakest major Mediterranean power (for an estimate of Antigonid manpower, see Billows, Kings and Colonists: Aspects of Macedonian Imperialism (1995)). Clarity comes then with the report that the socii had between them around 400,000 infantry and 43,000 cavalry, bringing the total number of men available for conscription by the Romans in an emergency to an absolutely stunning 770,000 men liable for conscription. That balance of forces was born out in the wars to come: the socii generally made up around half – sometimes a bit more, never much less – of each Roman army (that meant, by the by, that the average Roman served a few more years in the army than the average ally, on this see N. Rosenstein, Rome at War: Farms, Families and Death in the Middle Republic (2004)).

Consequently, it was Rome’s ability to mobilize their diverse, multicultural socii-system which provided them with the resources to withstand the battering they took in this iron century and come out on top as the uncontested hegemon of the Mediterranean world. Far from weakening Rome, it was the very diversity of its coalition which enabled it to mobilize the tremendous resources required. Had the Romans – like many of their Macedonian rivals – been unwilling or unable to make full use of the non-Romans of Italy, they’d have surely been defeated. And had the Romans insisted – like both their Macedonian and Carthaginian rivals – of imposing tribute and blatant subordination on the peoples they had subdued, they’d never have been able to maintain the loyalty of those socii through all of the setbacks (though, as you can see above, not all of the socii were so loyal). Instead, the Romans kept up the polite fiction that their socii were equal allies (even when they clearly weren’t), accorded them a share of the spoils, a share of the honor and didn’t interfere overmuch in their domestic affairs.

None of this is to make the Romans out to be nice, cuddly teddy-bears. The Romans were not nice for the sake of it. Instead at every stage of Rome’s Italian expansion, its leaders prioritized developing more military power over reaping other possible rewards of empire; that hard-nosed and bellicose set of priorities, not a commitment to tolerance or any such thing, led the Romans to a system which employed significant cross-cultural tolerance as a tool to raise and focus military power.

That focus is fairly evident when we look forward to the Social War.

The Social War: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back

Rome’s tremendous run of victories from 264 to 168 (and beyond) fundamentally changed the nature of the Roman state. The end of the First Punic War (in 241) brought Rome its first overseas province, Sicily which wasn’t integrated into the socii-system that prevailed in Italy. Part of what made the socii-system work is that while Etruscans, Romans, Latins, Samnites, Sabines, S. Italian Greeks and so on had very different languages, religions and cultures, centuries of Italian conflict (and then decades of service in Rome’s armies) had left them with fairly similar military systems, making it relatively easy to plug them in to the Roman army. Moreover, being in Rome’s Italian neighborhood meant that Rome could simply inform the socii of how many troops they were expected to supply that year and the socii could simply show up at the muster at the appointed time (which is how it worked, Plb. 6.21.4). Communities on Sicily (or other far-away places) couldn’t simply walk to the point of muster and might be more difficult to integrate into core Roman army. Moreover, because they were far away and information moves slowly in antiquity, Rome was going to need some sort of permanent representative present in these places anyway, in a way that was simply unnecessary for Italian communities.

Consequently, instead of being added to the system of the socii, these new territories were organized as provinces (which is to say they were assigned to the oversight of a magistrate, that’s what a provincia is, a job, not a place). Instead of contributing troops, they contributed taxes (in money and grain) and the subordination of these communities was much more direct, since communities within a province were still under the command of a magistrate.

We’ll get to the provinces and their role in shaping Roman attitudes towards identity and culture a bit later, but for the various peoples of Roman Italy, the main impact of this shift was to change the balance of rewards for military service. Whereas before most of the gains of conquest were in loot and land – which the socii shared in – now Roman conquests outside of Italy created permanent revenue streams (taxes!) which flowed to Rome only. Roman politicians began attempting to use those revenue streams to provide public goods to the people – land distribution, free military equipment, cheap grain – but these benefits, provided by Rome to its citizens, were unavailable to the socii.

At the same time, as the close of the second century approached, it became clear that the opportunity to march up the ladder of status was breaking down, consumed by the increasingly tense maelstrom of the politics of the Republic. In essence while it was obvious as early as the 120s (and perhaps earlier) that a major citizenship overhaul was needed which would extend some form of Roman citizenship to many of the socii, it seems that everyone in Rome’s political class was conscious that whoever actually did it would – by virtue of consolidating all of those new citizens behind them as a political bloc – gain immensely in the political system. Consequently, repeated efforts in the 120s, the 100s and the 90s failed, caught up in the intensifying gridlock and political dysfunction of Rome in the period.

Consequently, just as Rome’s expanding empire had made citizenship increasingly valuable, actually getting that citizenship was made almost impossible by the gridlock of Rome’s political system gumming up the works of the traditional stepwise march up the ladder of statuses in the Roman alliance.

Finally in 91, after one last effort by Livius Drusus, a tribune of the plebs, failed, the socii finally got fed up and decided to demand with force what decades of politics had denied them. It should be stressed that the motivations behind the resulting conflict, the Social War (91-87), were complex; some Italians revolted for citizenship, some to get rid of the Romans entirely. The sudden uprising by roughly half of the socii at last prompted Rome to act – in 90, the Romans offered citizenship to all of the communities of socii who had stayed loyal (as a way of keeping them so). That offer was quickly extended to rebellious socii who laid down arms and rejoined the Romans. The following year, the citizenship grant was extended to communities which had missed the first one. The willingness to finally extend citizenship won Rome the war, as the socii who had only wanted equality with the Romans, being offered it, switched sides to get it, leaving only a handful of the hardest cases (particularly the Samnites, who never missed an opportunity to rebel against Rome) isolated and vulnerable.

Silver Denarius minted by the Marsi during the Social War, showing the head of Bacchus (obverse) and a bull (the symbol of Italy) goring a wolf (the symbol of Rome) on the reverse. The Marsi, an Umbrian-speaking people, were so prominent in the war that it was sometimes called the Marsic War.

The consequence of the social war was that the slow process of minting new citizens or of Italian communities slowly moving up the ladder of status was radically accelerated in just a few years. In 95 BC, out of perhaps five million Italians, perhaps one million were Roman citizens (including here men, women and children). By 85 BC, perhaps four million were (with the remainder being almost entirely enslaved persons); the number of Roman citizens had essentially quadrupled overnight. Over time, that momentous decision would lead to a steady cultural drift which would largely erase the differences in languages, religion and culture between the various Italic peoples, but that had not happened yet and so confronted with brutal military necessity, the Romans had once again chose victory through diversity, rather than defeat through homogeneity. The result was a Roman citizen body that was bewilderingly diverse, even by Roman standards.

(Please note that the demographic numbers here are very approximate and rounded. There is a robust debate about the population of Roman Italy, which it isn’t worth getting in to here. For anyone wanting the a recent survey of the questions, L. de Ligt, Peasants, Citizens and Soldiers: Studies in the Demographic History of Roman Italy 225 BC – AD 100 (2012) is the place to start, but be warned that Roman demography is pretty technical and detail oriented and functionally impossible to make beginner-friendly.)

The Appian Road to Empire

The Social War coincided with the beginning of Rome’s wars with Mithridates VI of Pontus – the last real competitor Rome had in the Mediterranean world, whose defeat and death in 63 BC marked the end of the last large state resisting Rome and the last real presence of any anti-Roman power on the Mediterranean littoral. Rome was not out of enemies, of course, but Rome’s wars in the decades that followed were either civil wars (the in-fighting between Rome’s aristocrats spiraling into civil war beginning in 87 and ending in 31) or wars of conquest by Rome against substantially weaker powers, like Caesar’s conquests in Gaul.

Mithridates’ effort against the Romans, begun in 89 relied on the assumption that the chaos of the Social War would make it possible for Mithridates to absorb Roman territory (in particular the province of Asia, which corresponds to modern western Turkey) and eventually rival Rome itself (or whatever post-Social War Italic power replaced it). That plan collapsed precisely because Rome moved so quickly to offer citizenship to their disgruntled socii; it is not hard to imagine a more stubborn Rome perhaps still winning the Social War, but at such cost that it would have had few soldiers left to send East. As it was, by 87, Mithridates was effectively doomed, poised to be assailed by one Roman army after another until his kingdom was chipped away and exhausted by Rome’s far greater resources. It was only because of Rome’s continuing domestic political dysfunction (which to be clear had been going on since at least 133and was not a product of the expansion of citizenship) that Mithridates lasted as long as he did.

More than that, Rome’s success in this period is clearly and directly attributable to the Roman willingness to bring a wildly diverse range of Italic peoples, covering at least three religious systems, five languages and around two dozen different ethnic or tribal identities and forge that into a single cohesive military force and eventually into a single identity and citizen body. Rome’s ability to effectively manage and lead an extremely diverse coalition provided it with the resources that made the Roman Empire possible. And we should be clear here: Rome granted citizenship to the allies first; cultural assimilation only came afterwards.

Rome’s achievement in this regard stands in stark contrast to the failure of Rome’s rivals to effectively do the same. Carthage was quite good at employing large numbers of battle-hardened Iberian and Gallic mercenaries, but the speed with which Carthage’s subject states in North Africa (most notably its client kingdom, Numidia) jumped ship and joined the Romans at the first real opportunity speaks to a failure to achieve the same level of buy-in. Hannibal spent a decade and a half trying to incite a widespread revolt among Rome’s Italian allies and largely failed; the Romans managed a far more consequential revolt in Carthage’s North African territory in a single year.

And yet Carthage did still far better than Rome’s Hellenistic rivals in the East. As Taylor (op. cit.) documents, despite the vast wealth and population of the Ptolemaic and Seleucid states, they were never able to mobilize men on the scale that Rome did and whereas Rome’s allies stuck by them when the going got tough, the non-Macedonian subjects of the Ptolemies and Seleucids always had at least one eye on the door. Still worse were the Antigonids, whose core territory was as larger and probably somewhat more populous than the ager Romanus (that is, the territory directly controlled by Rome), but who, despite decades of acting as the hegemon of Greece, were singularly incapable of directing the Greeks or drawing any sort of military resources or investment from them. Lest we attribute this to fractious Greeks, it seems worth noting that the Latin speaking Romans were far better at getting their Greeks (in Southern Italy and Campania) to furnish troops, ships and supplies than the Greek speaking (though ethnically Macedonian) Antigonids ever were.

In short, the Roman Republic, with its integrated communities of socii and relatively welcoming and expansionist citizenship regime (and yes, the word ‘relatively’ there carries a lot of weight) had faced down a collection of imperial powers bent on maintaining the culture and ethnic homogeneity of their ruling class. Far from being a weakness, Rome’s opportunistic embrace of diversity had given it a decisive edge; diversity turned out to be the Roman’s ‘killer app.’ And I should note it was not merely the Roman use of the allies as ‘warm bodies’ or ‘cannon fodder’ – the Romans relied on those allied communities to provide leadership (both junior officers of their own units, but also after citizenship was granted, leadership at Rome too; Gaius Marius, Cicero and Gnaeus Pompey were all from communities of former socii) and technical expertise (the Roman navy, for instance, seems to have relied quite heavily on the experienced mariners of the Greek communities in Southern Italy).

Via Wikipedia, the route of the Via Appia (the Appian Way) which linked Rome to Brundisium (modern Brindisi) which was the best location to make the hop from Italy to Greece.

Via Wikipedia, the route of the Via Appia (the Appian Way) which linked Rome to Brundisium (modern Brindisi) which was the best location to make the hop from Italy to Greece.

Like the famous Appian Way, Rome’s road to empire had run through not merely Romans, but Latins, Oscan-speaking Campanians, upland Samnites, Messapic-speaking Apulians and coastal Greeks. The Romans had not intended to forge a pan-Italic super-identity or to spread the Latin language or Roman culture to anyone; they had intended to set up systems to get the resources and manpower to win wars. And win wars they did. Diversity had won Rome an empire. And as we’ll see, diversity was how they would keep it.

That said, next week we are going to turn from the military impacts of Rome’s expansionary citizenship model to the domestic impacts: how did all of this expansion, both within Italy and without, change the face of who got to be Roman?

Like this:

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK