Bitcoin’s stupendous power waste is green, apparently — bad excuses for Proof-of...

source link: https://davidgerard.co.uk/blockchain/2018/05/22/bitcoins-stupendous-power-waste-is-green-apparently-bad-excuses-for-proof-of-work/

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Bitcoin’s stupendous power waste is green, apparently — bad excuses for Proof-of-Work

Food 200 Acres remaining arable land

Data 100 zettabytes public ledger

Breathable Air 100 km3

Dyson Sphere Cryptomining 380 yottawatts

Laborers 2 million

someone who is good at the economy please help me budget this. my planet is dying

— comedyblissoption (after @dril)

Bitcoin advocates will take literally any news that you might think was Bitcoin going badly, and say “this is actually good news for Bitcoin!”

Certainly all the news I post about Bitcoin is actually good news for Bitcoin. There is no thing that is not good news for Bitcoin. Exchanges kicked out of China? Good news. Price crashes? Good news. Nuclear war sends civilisation spiraling down into the grim meathook Mad Max petrolpunk future? Good news, probably.

So … did you know that Bitcoin using 0.1% of all the electricity on earth, and 0.5% by the end of the year, is good?

Photo by Hans at Pixabay, CC-0

Why Bitcoin mining and proof-of-work exist

Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin’s inventor, needed a way to add verifiable transactions to a ledger, making sure nobody spent a coin twice — but without any central authority. This was the key requirement for Bitcoin.

(As I go through in chapter two of the book, Bitcoin had political design requirements that don’t work and can’t work. This is why it’s so weird and hard to understand, and why Bitcoin cultists shout twice as loud whenever it fails in yet another way.)

Proof-of-work mining is an ugly kludge of a hack — but it was the only way Nakamoto could think of to do this.

How Bitcoin mining works

Proof-of-work Bitcoin mining is built around wasting resources as fast as you possibly can.

You may have read in the papers about Bitcoin mining involving “complex calculations.” This is incorrect — none of the calculations are complicated. It’s working out a hash — a number calculated from a piece of data — like the check digit on your credit card number, but longer.

It’s very quick to go from the data to the hash, but impossibly slow to start from a desired hash and guess the data that would generate it.

A miner puts together a block of transactions that are waiting to be processed. They also tack on the hash of the previous block, and a random number (the “nonce”). They calculate the hash of the resulting block. If that hash is a small enough number … they win the bitcoins! And their block is added to the ledger — the blockchain.

The calculations required to build the blockchain ledger could be done on a 2007 iPhone or a Raspberry Pi — all the rest of the electricity is literally wasted, just to run a lottery to decide who gets the bitcoins this time.

All those computers doing Bitcoin mining just buy 14 sextillion lottery tickets every ten minutes, with one winner.

That’s the “work” that mining wants “proof” of — generating lottery tickets. You show your commitment, and how much you deserve the Bitcoins, by wasting power faster than everyone else.

If you want to win more, you need to add more computers, to generate more lottery tickets. This will soon lead to winners coming up more often than once every ten minutes. Nakamoto thought of this — and so, every 2016 blocks, the difficulty goes up or down, to keep it at one winner every ten minutes.

Mining ends up in an evolutionary arms race — a Red Queen’s race, where you run as fast as you can to stay in the same place — leading to ever-increasing power usage, for about seven transactions a second maximum, and two to four in practice.

Thus, Bitcoin is anti-efficient — the more bitcoin is used, the fewer transactions it can process per watt-hour. Bitcoin currently uses 300kWh per transaction, and by the end of 2018 this will be 900kWh — for the same two to four transactions per second.

Bitcoin uses as much electricity as all of Ireland. And everyone else is starting to notice — and they’re not happy.

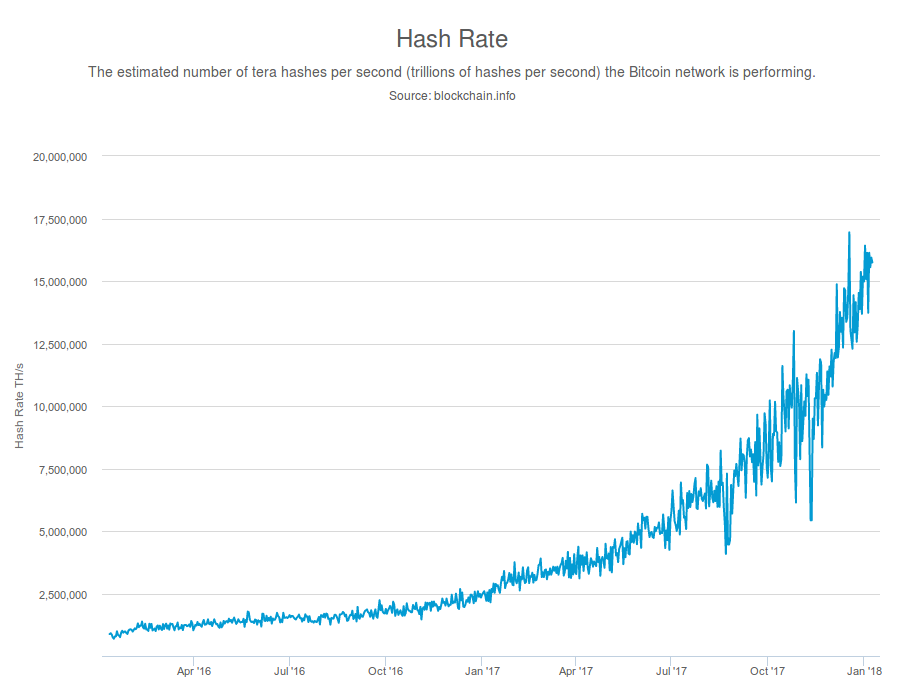

Bitcoin hash rate, January 2016 to January 2018

Bitcoin gets less efficient with time, not more efficient

Non-technical people often assume that Bitcoin will get more efficient as it goes on — like other technologies do. This isn’t the case at all.

With every other technology, the economic motivation is to reduce energy costs. But with Bitcoin, you make your bitcoins by spending as absolutely much energy as you can throw at the problem.

More efficient mining hardware comes out all the time — but it’s then set competing against other mining hardware of the same model, and the efficiency improvements don’t advance anything.

Thus, Bitcoin’s energy efficiency only gets worse with time — which is what we see.

Hal Finney — the second Bitcoin user, and Satoshi Nakamoto’s beta tester for Bitcoin 0.1 — noticed a couple of weeks after Bitcoin 0.1 was released that proof-of-work mining had obvious problems with externalities: “Thinking about how to reduce CO2 emissions from a widespread Bitcoin implementation.”

Thinking about how to reduce CO2 emissions from a widespread Bitcoin implementation

— halfin (@halfin) January 27, 2009

But “number go up” — the promise that Bitcoin will let you get rich for free — was reason enough for some startling intellectual parkour, as Bitcoiners tried to justify the unjustifiable.

But we need proof-of-work for security!

Anyone can check your new block of transactions is OK quickly — it’s generating a new block that’s difficult.

Proof-of-work means that if you want to fiddle what transactions get added to the blockchain, or fake the past contents of the blockchain, you need the mining power to do so.

This means the blockchain is a very robust transaction record … once you’ve got enough blocks after your transaction — enough “confirmations” — to be sure your transaction is in the longest version of the chain.

So advocates justify proof-of-work as necessary for security. This small part of Bitcoin is indeed stupendously secure — nobody’s broken it yet!

But nobody attacks a system at its strongest point — they go for the weak points. And Bitcoin has plenty of weak points. Hackers go for holders’ bad security, exchanges’ bad security, an amazing variety of straight-up scams (see chapter four) and so on. And they do really well out of this.

And if you steal someone’s bitcoins — they’re yours now. Because Bitcoin transactions are irreversible.

Bitcoin advocates brag about the six-inch-thick steel blast door — and think making it a twelve-inch-thick blast door is super-important — but they ignore the bit where it’s in a plastic frame.

But we need proof-of-work for decentralisation!

Decentralisation is a hugely important part of the Bitcoin pitch. It is essential to Bitcoin’s political pitch that there can be no central controlling body. If a single miner got 51% of mining power, they could mess with the blockchain in all sorts of ways.

Mining was a land of opportunity back in the early days — anyone could participate, easily! Per Nakamoto, in February 2009:

You could say coins are issued by the majority.

Bitcoin succeeded in widely distributing mining, and hence payouts … for a few years.

The trouble is that proof-of-work has economies of scale. The larger your mining operation, the more efficient it is — the more hashes it can calculate per watt-hour. This means proof-of-work mining naturally centralises.

Mining went from being calculated on computer CPUs, to being calculated on video cards, to being calculated on FPGAs — Field-Programmable Gate Arrays, chips you can program the function of — to ASICs — Application-Specific Integrated Circuits, that do one specific job super-efficiently and nothing else.

By late 2013, ASIC-based miners were coming on line. But by early 2014, one company, Bitmain, made most of the chips, and continues to control cryptocurrency mining. By mid-2014, one mining pool, GHash, had gone over 55% of all mining.

The majority of Bitcoin mining in 2018 is done by only three mining pools. This is central issuance — decentralisation is long dead. But we’re still wasting all that power.

But only proof-of-work gives us true immutability!

Bitcoin evangelist Andreas Antonopoulos doesn’t address objections to proof-of-work in 2016’s The Internet of Money. By 2017, and The Internet of Money Volume Two, he couldn’t get away with this — so chapter 4 is about “Immutability and Proof-of-Work”:

A new maximum was defined, a new maximum in terms of what it means to be immutable for a digital system. Nothing is as immutable as bitcoin; bitcoin defines the end of that scale at the moment, so it redefines the term immutable.

… The characteristic that gives bitcoin its tamper-proof capability is not “the blockchain”; it’s proof-of-work. Proof-of-work is what makes bitcoin fundamentally immutable.

This is a plausible claim — the Merkle tree data structure makes the Bitcoin blockchain tamper-evident, but it’s the amount of mining you’d have to do that makes it unalterable in practice.

But does this justify the massive expenditure? Antonopoulous is very impressed by the concept of true immutability:

You may think “historically important” is a pretty heavy term. Why is it going to be “historically important”? Because if bitcoin continues to work the way it’s working today, we are introducing a new concept, which is a form of digital history that is forever. If that history lasts 10 years, that’s impressive; if it lasts 100 years, that’s astonishing; if it lasts 1,000 years, it becomes an enduring monument—an edifice—of immutability. A system of forever, unshakable history that is truly a monument of our civilization. We have to consider the possibility that will happen.

… You can see evidence of proof-of-work systems throughout human civilization. There is some big pointy proof-of-work in Cairo: the pyramids. There is some big stone proof-of-work in Paris: the Cathedral of Notre Dame. In fact, proof-of-work is something that our civilization does quite often.

That is — the last record of our civilisation will be SatoshiDice gambling spam, the drugs you bought on the Silk Road several years ago, and some illegal pornography.

The Bitcoin blockchain not only can’t scale to useful transaction rates — it doesn’t scale to useful information, only to a ledger of Bitcoin transactions. Truly immutable timestamps could be useful — assuming anyone finds a timestamp use case so important that it warrants a country-sized percentage of the world’s electricity consumption.

This is the sunk cost fallacy: just because you spent a lot of effort on something doesn’t mean it was worth it, or that it’s useful going forward.

But Bitcoin is good because it uses so much power!

Bitcoin maximalists favour the argument that Bitcoin is so uniquely important and valuable, and brings so much to humanity, that it’s worth all the electricity we spend on it — because there’s no other way to get that.

Saifedean Ammous’ book The Bitcoin Standard goes further — proof-of-work is good and necessary because it spends so much electricity to generate bitcoins (pp. 218-219):

Although solving these problems might initially seem a wasteful use of computing and electric power, proof-of-work is essential to the operation of Bitcoin. By requiring the expenditure of electricity and processing power to produce new bitcoins, PoW is the only method so far discovered for making the production of a digital good reliably expensive, allowing it to be a hard money.

The question of whether Bitcoin wastes electricity is at its heart a misunderstanding of the fundamentally subjective nature of value. Electricity is generated worldwide in large quantities to satisfy the needs of consumers. The only judgment about whether this electricity has gone to waste or not lies with the consumer who pays for it. People who are willing to pay the cost of the operation of the Bitcoin network for their transactions are effectively financing this electricity consumption, which means the electricity is being produced to satisfy consumer needs and has not been wasted. Functionally speaking, PoW is the only method humans have invented for creating digital hard money. If people find that worth paying for, the electricity has not been wasted.

That is: proof-of-work is the only way yet found to do the Bitcoin trick. And if people want to spend money on it, not only is that their business and nobody else’s, but it is therefore not a waste.

This assumes the unalterable Bitcoin blockchain is intrinsically worth it, and that externalities aren’t anyone else’s business. The former is highly questionable to anyone who isn’t already a Bitcoin fan, and the Bitcoin fans are having more and more trouble convincing the non-fans of the latter.

But Bitcoin lets us coordinate people worldwide like nothing before it!

Nick Szabo argues, in his essay “Money, blockchains, and social scalability,” that — just as it’s worth spending computing power on nice user interfaces — it’s worth spending electricity to let us do the things only Bitcoin potentially allows us to do:

Instead, the secret to Bitcoin’s success is that its prolific resource consumption and poor computational scalability is buying something even more valuable: social scalability. Social scalability is the ability of an institution — a relationship or shared endeavor, in which multiple people repeatedly participate, and featuring customs, rules, or other features which constrain or motivate participants’ behaviors — to overcome shortcomings in human minds and in the motivating or constraining aspects of said institution that limit who or how many can successfully participate. Social scalability is about the ways and extents to which participants can think about and respond to institutions and fellow participants as the variety and numbers of participants in those institutions or relationships grow. It’s about human limitations, not about technological limitations or physical resource constraints.

That is — Bitcoin is good and useful and worth spending this power on, for the fantastic new things it lets us do, to coordinate huge numbers of people around the world!

The obvious answer is that just having the Internet at all turns out to do almost all the interesting bits of worldwide social coordination.

Szabo admits this, but asserts that Bitcoin is totally worth running on top so that we can coordinate internationally using a form of money with certain properties that he asserts are essential to money. These properties turn out to be … the pitch for Bitcoin.

This falls to the obvious objection — Bitcoin has not, in fact, turned out to be good at the things it was pitched as. Whatever you might claim Bitcoin’s fabulous potential to be — in practice, it’s a bad payment system hooked to a bubble-prone speculative commodity, that has resoundingly failed to scale. Mostly, it’s replayed the history of finance and scams on fast-forward, hitting its head on every step on the way down — and not much else at all.

Bitcoin does all of its possible jobs — currency, speculative commodity, store of value — worse than any alternative, and its economics are fundamentally silly and can’t possibly work. I submit that this is not worth 0.5% of the world’s electricity. As user interface engineering, Bitcoin fails the test of feasibility.

But proof-of-work helps the ecology!

This is a real-life argument: Bitcoin’s stupendous power consumption, wasting electricity to win coins, is actually good news for the ecology.

The argument is usually that Bitcoin’s tremendous power usage will motivate more efficient power generation. Therefore, Bitcoin is good for the world, and you should buy Bitcoin.

(They don’t say that last bit outright, but you know it’s the point.)

In “How Bitcoin could drive the clean energy revolution,” Peter Van Valkenbergh of CoinCenter details how heavy industry drives electricity efficiency — and never mind that proof-of-work is constructed to be anti-efficient:

The fact is that the Bitcoin protocol, right now, is providing a $200,000 bounty every 10 minutes (the bitcoin mining reward) to the person who can find the cheapest energy on the planet. Got cheap green power? Bitcoin could make building more of it well worth your time.

This just states that a theoretical incentive might exist. He doesn’t show that the incentive is realised — and he doesn’t show that it makes Bitcoin’s energy use worth it.

What actually happens when Bitcoin miners come to town is that they use so much electricity that it drives local power prices through the roof. Hydroelectric power is cheap, but the limited capacity is often pre-allocated.

Plattsburgh, in upstate New York, suffered this in late 2017 and early 2018, when two cryptocurrency mining operations used 10% of the city’s power supply — sending the city over its monthly quota of 104 MWh of cheap hydroelectric power (4.92c/kWh) from the Municipal Electric Utility Association on the St Lawrence River. This forced them to buy expensive outside power at 37c/kWh, sending the bill for the average home up by $30 to $40. Plattsburgh imposed an 18-month ban on crypto mining. Chelan, Washington, imposed a similar ban.

There used to be a slight argument that Bitcoin mining in China was just using overbuilt power capacity that wasn’t otherwise being used, as these power plants weren’t well-connected to the national grid. And a lot of this was hydroelectric, so wasn’t a CO2-generating disaster. (Though a lot was coal.) But now that these power plants are getting better-connected, China has much better uses for the power, and is pushing the miners out.

Ari Paul has claimed that “Bitcoin is incentivizing renewable energy research and growth at an unprecedented pace.” When pressed, he first demanded critics prove his claim for him, then eventually gave the example of someone he knew who bought solar panels to power a mining operation. This might count as “growth,” but Paul so far hasn’t supported his claim of “research,” let alone at an unprecedented pace.

CoinCenter is so wedded to their Bitcoin energy efficiency pitch that they tried to commission an economist to … reach their predetermined conclusions:

We’re looking for a well-credentialed energy economist or similar expert from whom we may be able to commission a well-sourced report on Bitcoin’s energy use, including:

1. Address factual inaccuracies in how some have calculated the current energy use, and offer a correct estimation

2. Offer justification for the energy expenditure, especially relative to existing money systems or data processing

3. Explain that long term incentives are for miners to find most efficient energy sources, thus developing those sources

One industry expert responded by questioning why a report from an economist was necessary if @coincenter knew what the conclusions would be ahead of time. pic.twitter.com/owCcC72lPM

— Nathaniel Popper (@nathanielpopper) February 12, 2018

You’d almost think their motivation had more to do with love of Bitcoin than of saving energy.

But what about the entire financial system and everyone in it?

“But what about all the energy banks use?” is a perennial Bitcoiner counterargument.

They almost never include actual numbers — they seem to think these are just words to throw out as quick counterarguments, and not checkable numbers that exist. They will try to include the entire financial system, everyone in it, and everything it does.

(This Andreas Antonopoulos video is a good example — note how he just lists a string of possible financial system expenses off the top of his head, with not a number in sight.)

It’s obvious that, say, Visa can’t possibly use power at the rate Bitcoin does, even if you include every Visa, Inc. expense and facility — if it did, you’d see it in the cost of every transaction, as you do in Bitcoin. And nobody would buy things with Visa, just as they don’t buy things with Bitcoin.

Bitcoin energy usage isn’t directly related to the amount of transactions going through it. But if Bitcoin advocates insist on comparing Bitcoin to the financial system on its energy consumption, then we should in fact look at how much work each one gets done for the energy it’s spending.

Let’s run the numbers. CapGemini and BNP Paribas’ World Payments Report 2017 shows 433.1 billion non-cash payments worldwide in 2015, and a projected 726 billion in 2020.

Let’s be generous and assume there will only be as many transactions in 2018 as there were in 2015, and Bitcoin transactions will only use 300kWh each, as they do now. If the existing financial system used as much power as Bitcoin, then just the non-cash payments would use 4.331×1011 transactions, times 3×105 watt-hours per transaction — which gives 1.3×1017 watt-hours, or 133 petawatt-hours.

The worldwide production of energy — all kinds of human-harnessed energy, not just electricity — in 2015 was 169.5 petawatt-hours. It’s frankly implausible that, even if you take literally the whole financial industry and everything it does everywhere, it would come anywhere near that number — unless you stretch the comparison until you equate “the financial system” and “civilisation.” Just electricity worldwide in 2015 was 15.1 petawatt-hours, by the way.

There are two important points this stupid claim about the financial system misses.

Firstly — all the other things Bitcoiners compare themselves to have every incentive to reduce their power use, and become more efficient. (The pressure is social as well as financial — banks care quite a lot about reducing environmental impact.) Bitcoin, however, doesn’t just fail to scale — it anti-scales. The more it’s used, the less efficient it is — in transaction speed and cost, in storage requirements … and in power usage.

And secondly — Bitcoin doesn’t replace the current financial system. (And can’t replace the current financial system, ’cos it doesn’t scale.) For all practical purposes, Bitcoin works only in terms of the conventional currency system. The cryptocurrency economy is negligible. Bitcoin’s only use case is as a speculative commodity, and slightly as a bad payment system.

The usual excuse at this point is to say that the Lightning Network — a new low-overhead payment network being built on top of Bitcoin — will fix it all, and give us thousands of transactions for each watt-hour spent mining bitcoins.

But the Lightning Network can run on top of lots of cryptocurrencies — e.g., there’s already a Litecoin version. It doesn’t rely on its underlying cryptocurrency being Bitcoin, or even a proof-of-work coin. You could run the Lightning Network on top of a dollar-substitute token, if it was a good payment network that non-Bitcoiners would want to use — and not just a name that Bitcoiners wave about as a future excuse for present failures.

The future

Bitcoin will never leave proof-of-work, as it has no governance that could possibly swing such a change.

Ethereum’s governance is much more coherent. Ethereum is pinning its hopes to its Casper proof-of-stake initiative, in which coins are issued by a less wasteful consensus algorithm than proof-of-work. I think Casper is likely to centralise Ethereum even more — but nobody will care as long as they can still run ICO scams on top of it, and the price of ETH doesn’t crash.

And even though Casper is starting as only a bit proof-of-stake, Ethereum will still be able to pitch itself as nicer and less of a horrifying environmental disaster than Bitcoin. Also, Ethereum advocates tend to be much more business-friendly, and not ranting nutters like Bitcoin maximalists.

I don’t expect this post to convince Bitcoin advocates, because nothing will convince a Bitcoin advocate. But I do hope the smarter ones will stop making blitheringly stupid claims about how great proof-of-work is.

Your subscriptions keep this site going. Sign up today!

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK