Three Comics For Understanding Unix Shell

source link: http://www.oilshell.org/blog/2020/04/comics.html

Go to the source link to view the article. You can view the picture content, updated content and better typesetting reading experience. If the link is broken, please click the button below to view the snapshot at that time.

Three Comics For Understanding Unix Shell

Three Comics For Understanding Unix Shell

I just optimized Oil's runtime by reducing the number of processes that it starts. Surprisingly, you can implement shell features like pipelines and subshells with more than one "process topology".

I described these optimizations on Zulip, and I want to write a post called Oil Starts Fewer Processes Than Other Shells.

That post feels dense, so let's first review some background knowledge, with the help of several great drawings from Julia Evans.

1. The Shell Language and the Unix Kernel

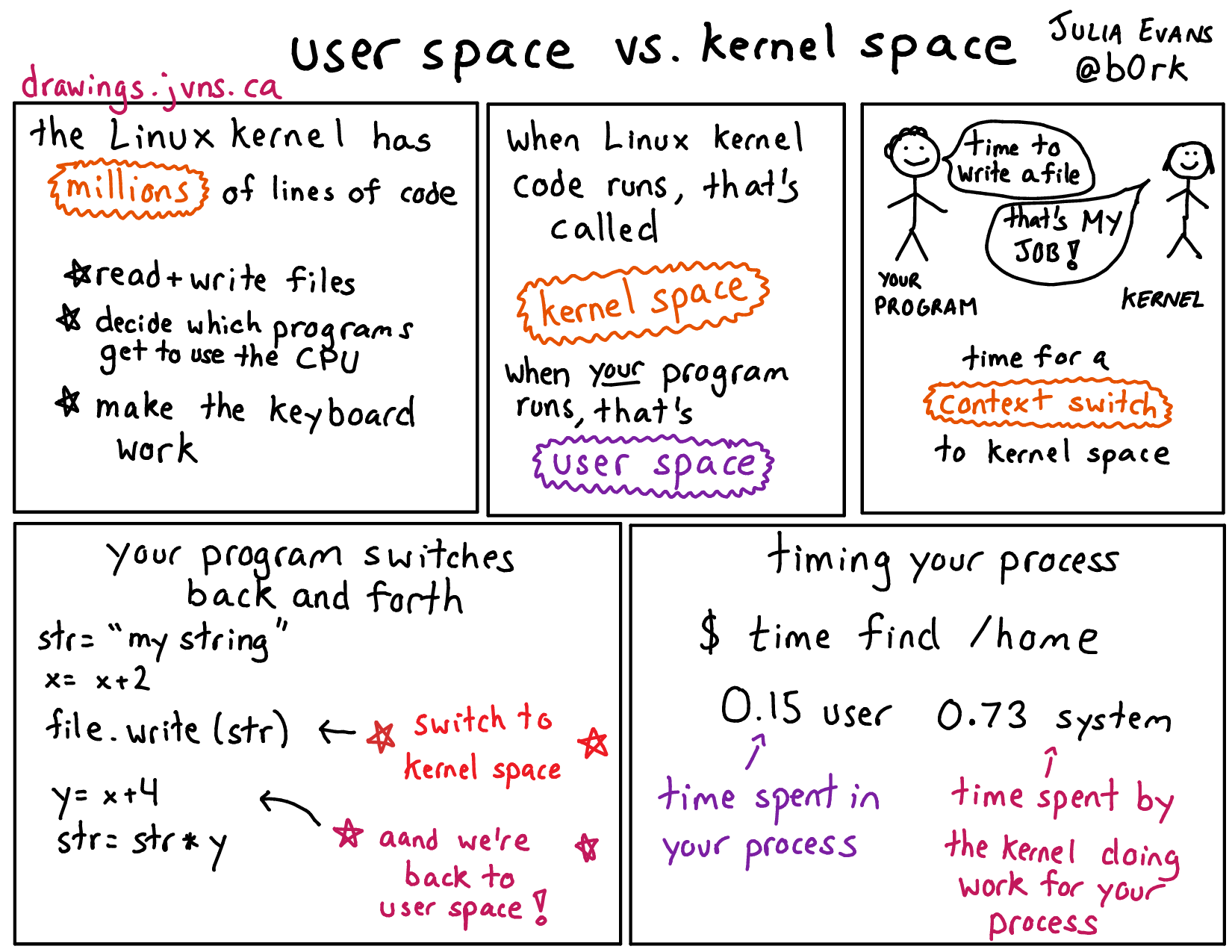

User space and kernel space are key concepts for understanding shell. Why?

- The shell mostly lives in user space, but common constructs like

ls /binand$(dirname $x)require support from the kernel to start processes. - That is, a shell is a process that starts other processes. Unlike programs in say Python or C, almost all shell programs involve many processes. (I'll explain why this is a good thing later.)

- In old operating systems, command shells were built into the kernel. The Unix/Multics design of putting the shell in user space enables Oil. We don't have to modify Linux to use Oil, and it can run on other Unix systems like OS X and FreeBSD.

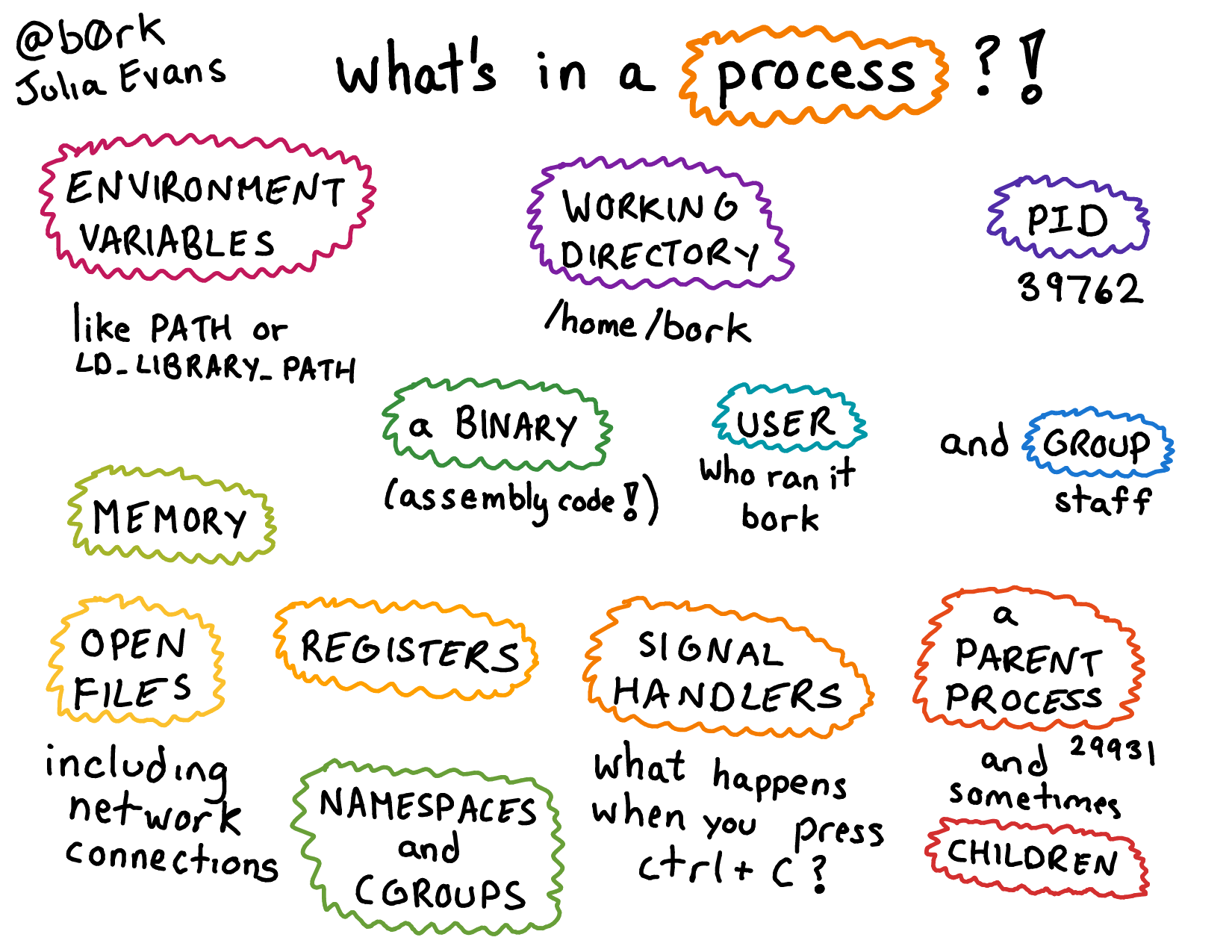

2. The Shell Controls What's in a Process

Shell has dedicated syntax and builtin commands to manipulate its own process state, and thus the inherited state of child processes. You can:

- Control environment vars with

export. - Change the working directory with

cd,pushd, andpopd. Retrieve it withpwdor$PWD. - Read the process ID from the

$$variable, and the parent PID from$PPID. - Use the

trapbuiltin to register code to run when the process receives a signal (e.g.SIGINTor Ctrl-C). - Wait for child processes to stop with the

waitbuiltin. - Use the shell keyword

timeto ask the kernel how long a process has taken to run. (See the last pane of the first comic.)

In other words, shell is a thin layer over the process abstraction provided by the kernel. Processes used to be thought of as virtual machines, although that term now has a different connotation.

Interlude: Two Kinds of Processes

It's not obvious from the syntax, but there are two different kinds of processes in a shell program:

-

Those that run a different executable, i.e. assembly code that's not in

/bin/shor/usr/local/bin/oil. Examples:$ ls # 1 new process and 1 executable (usually) $ ls | wc -l # 2 new processes and 2 executables (usually)After calling

fork()to create a process, the shell also callsexec()to run code in/bin/lsor/usr/bin/wc. Theexec()system call loads and starts a new "binary image" in the current process. -

Those that run the same executable. For example, the left-hand-side of this pipeline

# at least 1 new process, but no new executables $ { echo a; echo b; } | read xdenotes an independent copy of the shell interpreter, created with the

fork()system call. Noexec()call is needed.Is it inefficient to start a process for those two statements? Not really, no. See this related comic: Copy On Write.

The (usually) qualifiers above are what the next post is about. I

optimized the usage of fork() and exec() syscalls in Oil. I was surprised

to learn that all shells do this to some extent.

3. A Pipe Has Two Ends

I really like the red and blue dots in this drawing. It's an intuitive way of

explaining the pipe() system call, which forces us to understand file

descriptors.

I think of file descriptors as "pointers" from user space into the kernel. They can't literally be pointers, because user space and kernel each have their own memory. So instead they're small integers that are offsets into a table in the kernel.

Related Comics:

The next post will discuss shopt -s lastpipe, a bash option that

implements zsh-like pipeline behavior.

What I'd Like to Draw

I still want to get more done in 2020 by cutting scope, but I'd like to illustrate these related concepts:

-

There are three processes involved in

ls | wc -l.- The shell, which calls

pipe(). Importantly, the file descriptors returned bypipe()are inherited by children. - Its child

ls, which uses the red end of the pipe it inherits. - Its child

wc -l, which uses the blue end.

- The shell, which calls

-

The difference between

fork()andexec(). I explained this above, but a drawing would make it clearer. If you know of one, let me know in the comments.- The shell does important things between

fork()andexec(), like manipulate file descriptors. - Windows doesn't have the distinction between creating a process and loading executable code into it.

- The shell does important things between

I'll show that Oil starts fewer processes than other shells for snippets like:

date; date

(date)

date | wc -l

echo $(date)

And I'll describe how I measured this with strace.

Appendix: Related Comics

These comics are also related to Oil, and I may reference them in future posts:

- libc. The C standard library is the only required dependency of a shell.

- Bash Tips. The first point, "no spaces", echoes The Simplest Explanation of Oil.

- The Page Table (again). Processes are implemented with dedicated hardware (an MMU). That's one thing that makes them powerful and reliable.

For what it's worth, I just bought a printed set of zines, Your Linux Toolbox, which have related but different content. You can also buy e-books on wizardzines.com.

Recommend

About Joyk

Aggregate valuable and interesting links.

Joyk means Joy of geeK